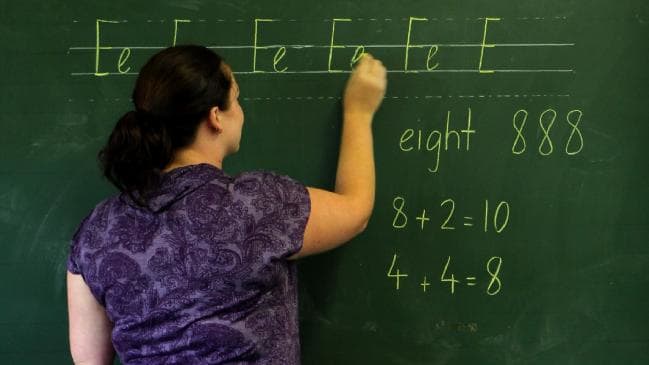

Australia is facing an education crisis as hordes of disillusioned and burnt-out teachers flee the profession, with potentially damaging ramifications for the whole country.

Former educators have spoken to news.com.au about the “miserable” conditions driving an estimated 40 per cent of graduates to quit within the first five years of entering the workforce.

And at the other end of the spectrum, a growing number of veterans are walking away from the job in frustration.

“By the time I walked out of that classroom on my very last day as a teacher, I didn’t feel any sadness or regret — just relief,” former teacher Sally Mackinnon, who quit after 13 years, told news.com.au.

“I was at the end of my tether. My time was up. I didn’t want to be a teacher who just didn’t give a crap and was turning up for a job. Kids deserve more than that. They deserve passion and energy. But it’s so hard to maintain that, and I wasn’t alone.”

Research and first-hand accounts of former teachers indicates a potent mix of stress, workload, parental abuse and pay are combining to push many to breaking point.

A decade since leaving, Ms Mackinnon knows of only one or two ex-colleagues who are still employed full-time, with most having left or moved to part-time hours.

“These are really good teachers,” she said. “That makes me really sad.”

Adam Voigt became a school principal at just 35 after a long run as a respected teacher, but he also walked away from his dream career due to its crushing reality.

“It’s not just about paying teachers more. It’s not just about improving conditions. We’ve got to get sophisticated about how we tackle the problem to meet the entire workforce’s needs.”

A BROKEN SYSTEM

Since leaving, Mr Voigt has become an education consultant who works with individual schools to improve their culture and conditions, addressing the issues forcing teachers out.

“If you view the education workforce as a bucket and you want high-quality water in it, you can pour better quality in or you can fix the two big holes in the bottom,” Mr Voigt said.

“The first thing most would do is fix the holes, but we’re not.”

Labor this week announced a plan to raise university entrance scores for education degrees, in a bid to lift teacher quality.

While it was an “admirable” idea, Mr Voigt said it would do little on its own to help.

“Nationally, we need to have the uncomfortable conversation around pay and conditions. Tanya Plibersek wants the same level of competition to get into teaching as you find with medicine. You’ve got to pay teachers like doctors then.

“What’s the point of luring them into teaching degrees if they quit after a few years of working? It’s a waste of time and energy.

“We can’t wait until teachers are completely wrung out to deal with why they’re unhappy. We need to figure out how we’ve gotten here in the first place.”

Growing up, Ms Mackinnon loved school and adored her teachers, and always wanted to follow in her mum’s footsteps by becoming an educator.

After graduating, she went to university and then achieved her lifelong dream, which she “absolutely loved”.

“I threw myself in 100 per cent. I was dedicated and did the long hours, my life revolved around the classroom,” she said.

“But at about the 10-year mark something happened. I wasn’t sure I could continue to work as passionately as I had. It was time to move on.”

A combination of factors contributed to tear away at her spirit — the constantly growing and enormous burden of administrative tasks one of the big issues.

“I went from being able to spend most of my time dedicated to my students, planning great lessons and putting my energy into my classroom, to being taken over by meetings, paperwork and checking boxes for the sake of it,” Ms Mackinnon said.

It’s something Mr Voigt can relate to, saying the role of a principal has shifted from school leader and mentor to corporate manager.

Most of the paperwork he had to do was “pointless” box-ticking and red tape that offered little-to-no value to the school environment, he said.

“There was a study about how principals spend their time and less than one per cent was talking to teachers about students. That should be the core business of their role.

“For principals, it’s the administrative load they’re expected to carry. The sheer volume of paperwork is absolutely enormous. What you’re expected to deal with and the hours you’re expected to work are huge.

“They’re sitting in their offices forced to write reports and do admin when they should be helping teachers to become better teachers.”

Another factor that current and former teachers say is making the job a nightmare is the attitude of parents, which seems to have shifted dramatically in the past decade.

Mr Voigt said the “blame game” was becoming worse, with mums and dads expecting schools to be a single solution for every requirement.

“We wind up crowding schools with nonsense. Instead of teaching kids how to learn and to be good citizens, we teach them how to drive, how to eat, how to have manners … all of those things that take up precious time.”

And when a kid gets in trouble, the teacher inevitably does too, he said.

“Thirty years ago, if you got in trouble at school then you were in trouble twice — once there and again at home,” he said.

“Now, the parent goes down to the classroom and thumps desks and complains. We’re no longer on the same page about turning these kids into good citizens. We’re arguing about who’s right.”

An assistant principal in Sydney, who asked not to be named, said educators were now focusing on how to deal with aggressive parents.

“Part of initial meetings with my new colleagues at a new school included plans to support me as I cop abuse from both parents and students.

“We (are meant to) report each incident that occurs … but many don’t because they simply don’t have time.”

Ms Mackinnon also said students and their parents began to change as she was leaving the job — something her teacher friends say only got worse with the rise of social media and smartphones.

“The perception of being a revered position has gone and it’s quite thankless,” she said.

TEACHERS ARE MISERABLE

Ms Mackinnon entered a new career as a personal stylist and started her own business in Melbourne 10 years ago, which has been a huge success.

She’s occasionally asked if she misses her former life and whether she ever considered going back one day.

“I feel sad to say it, but no, absolutely not,” Ms Mackinnon said.

“I caught up with a girlfriend recently who is still teaching and she said her job feels more like being a policewoman. She’s one of the few that still is teaching, by the way. Most of my friends have either left or gone part-time.”

Another former teacher, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, said there was a risk of future educators “becoming so disillusioned that they don’t enter it in the first place”.

“Teaching is the most incredibly rewarding job and I’d hate to see there ever being a time when society runs out of quality teachers,” they said.

Meanwhile, the former assistant principal said he was burning out and “doing damage to myself” but, since leaving, couldn’t be happier.

“It’s mainly about the workload and level of disrespect from parents,” he said.

There was a growing awareness about the issues facing teachers — and the national consequences of the exodus from the workforce, Mr Voigt said.

However, the conversation still has negative undertones that needed to be addressed.

“People seem to have lost trust in schools and teachers over a long period of time,” Mr Voigt said.

“The conversation is about how they should just be happy because they get to knock off at 3.30pm and they get lots of holidays. The teaching workforce isn’t soft. They’re representative of any workforce and they’re landing in awful conditions.”

CHILDREN ARE SUFFERING

The consequences of the worsening issue affect more than just parents, with Australia running the risk of an entire generation of kids receiving a sub-par education.

A report by the Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership warned the mass exodus of teachers would lead to “the loss of quality teaching graduates, which could in turn impact the development of a strong workforce of experienced, high-calibre teachers”.

For graduates, most enter the profession with “positive motivations to teach … and a desire to be good teachers”, the report said.

But a high workload and a lack of support cause many to become disillusioned and exit early into their careers.

Across the board, a government report in 2014 indicated that 5.7 per cent of the teaching workforce was walking away each year.

“The students will suffer,” Mr Voigt said. “They already are. We have a big problem and we need to do something.”

In a paper for the Australian Journal of Teacher Education, Shannon Mason from Griffith University said teacher attrition is “costly, both for a nation’s budget and for the social and academic outcomes of its citizens”.

And the problem would be worst-felt in non-metropolitan areas, in undesirable schools and in specific discipline areas such as senior mathematics and science, Ms Mason warned.

“The teaching profession is becoming devalued in a context of heightened pressure to perform on standardised testing, intensificration of teachers’ workloads and a broadening of the role that teachers play in the lives of their students,” she said.

Source of the notice: https://www.news.com.au/finance/work/at-work/australian-teachers-are-at-the-end-of-their-tethers-and-abandoning-the-profession-sparking-a-crisis/news-story/43c1948d6def66e0351433463d76fcda

Users Today : 90

Users Today : 90 Total Users : 35460107

Total Users : 35460107 Views Today : 111

Views Today : 111 Total views : 3418742

Total views : 3418742