Luis Bonilla-Molina is a researcher and prolific writer whose work takes a critical look at educational and pedagogical models. He coordinated President Chavez’s international advisors team from 2004 to 2006 and was director of the Miranda International Center (CIM), an internationalist research initiative in Caracas, from 2006 through 2019. Bonilla-Molina is also the former president of the Governing Council of UNESCO’s International Institute for Higher Education in Latin America and the Caribbean, and the current co-director of the Latin American Council for Social Sciences’ (CLACSO) International Investigation Center “Other Voices on Education.”

The essence of the Bolivarian Revolution was a process involving the radical expansion of democracy. Of course, in a process of substantive democratization, education plays a key role. What can you tell us about the educational reform that Hugo Chavez promoted and its relation to the wider democratization of society?

Education is an enabling right [“derecho habilitante”] to all other human rights and Chavez understood this. Broadening access to education opens the path towards the expansion of all other rights.

When Chavez came to power, in the midst of a profound social crisis, there were many problems to be addressed but he focused on educational inclusion. He understood that the democratization of society, which was the driving force for the Bolivarian Process, would only happen through educational inclusion.

From the early days of his presidency, Chavez promoted an inclusive model, but this model clashed with the Education, Culture, and Sports Ministry dynamics. In fact, he was clashing head-on with the existing institutional framework as a whole. That is why he developed the educational missions model: those, in fact, became the route to bypass institutional barriers, and they were tremendously efficient at reaching the people.

There were so many achievements in this period! In fact, I doubt that any other country in the world achieved such widespread educational inclusion in so brief a period. One of the goals was the end of illiteracy, from which about a million people suffered. UNESCO declared Venezuela “territory free of illiteracy” in 2005 [the literacy program was launched in 2003 with Cuban support].

After the literacy program, which came to be known as Mision Robinson, there was an effort to open the doors to those men and women who had wanted to go to college or high school or even primary school, and who had been expelled from the system. The Ribas [pre-university level schooling] and Sucre [university level] Missions worked to widen access.

I remember that I once visited a Mision Sucre education center in Tachira state, where I met a 70-year-old student. When I asked her why she was studying, she told me: “More than merely having a title, what I want is to know what it feels like to be a university student.” Her words evoke the profoundly human character of inclusion.

Robinson Mission classroom, 2013. (VTV)

It is clear that there were huge advances in educational inclusion. Nonetheless, as a professor at the Bolivarian University, I’m aware that there are still many problems to be resolved. What are the pending tasks in the educational reform promoted by Chavez?

The problem for me lies in that we, the left, didn’t come up with an educational project beyond inclusion. Inclusion is fundamental to achieve all other political and social demands, but there wasn’t enough debate about the pedagogical model. Around 2008 we promoted a space to debate the model. We were concerned that much of the public discourse around education centered around the need to move toward the “Venezuelan pedagogical model”… but what does that really mean?

Talking about the “Venezuelan pedagogical model” was a profoundly depoliticized and problematic way to address the issue at hand. What do Simon Rodriguez and Cecilio Acosta [a 19th century liberal reformer] have in common? What connects Andres Bello and Luis Beltran Prieto Figueroa [*]? The history of the pedagogical movement has to do with the correlation of forces, which didn’t favor the popular classes for most of our history. In other words, in Venezuela, most of the pedagogical thought has been closer to [established] power than to the popular masses.

The euphemism “Venezuelan pedagogical thought” is profoundly empty. This becomes evident, for example, when Prieto Figueroa is referred to as a “theorist of socialist education.” Yet Prieto Figueroa’s educational project is a clear expression of the bourgeois education system that would emerge after the 1958 liberal democratic revolution. It is true that at the end of his life, in the 1970s, Prieto Figueroa embraced the socialist project, but his work in education goes hand in hand with bourgeois liberalism!

So, again, there was some debate in 2008 and 2009, but we ran into a bottleneck. The left does not seem to understand that debate is inherent in class struggle. We seem to think that a public debate hurts the revolution, when, on the contrary, it is silences and complacencies that hurt the revolution.

Those were years when there were many latent debates, with some becoming public but, at the same time, those debates were shunned. In fact, there was one debate in which Chavez participated, at the International Miranda Center… Years later, in 2011, Chavez publicly acknowledged that the debate had been useful.

But going back to the educational model itself: we are in a sort of limbo!

Mind you, I’m not talking about curricular reform. When Rodulfo Perez [2016] was minister, we had a debate about the issue of curricular reform. My position is that a curricular reform does not solve anything. Changing the curricula is not the solution because the contents are not the key problem. Changing the Koran for the Bible won’t bring about a real change. Instead, we must reconceptualize the educational model as a whole.

To give you an example, we advocate school autonomy to address both local and national needs, and to permit innovation. We are not talking about autonomy as is proposed by neoliberalism, so that every school becomes a corporation. We advocate autonomy so that communities can define priorities according to their conditions and needs. Needless to say, all that has to happen within the framework of a national educational project with input from teachers, students, and the nation as a whole. A new national debate from below is urgent.

Nobody, not even the Venezuelan right-wing, can deny the tremendous advances in inclusion in the first years of the Bolivarian Revolution, but there is a big deficit in the construction of a pedagogical project with a revolutionary horizon.

The lack of a pedagogic model led to other errors, such as the canaimitas. Chavez understood that computers and access to the internet should be democratized. However, there was a problem and I actually expressed my concern to him. Computers were given to students. Meanwhile neither teachers nor educational centers had computers. That was a defective strategy, and we are paying the consequences now. For a pedagogic strategy to be successful, it has to be lasting and incorporate both the teachers and the educational centers. Today, most teachers continue without computers, which is all the more serious in the context of the lockdown.

We have an additional problem not only among the government leadership but within the left as a whole. We talk about capitalism and imperialism, but we don’t study the phenomena and we end up reproducing its logic. The US is the big unknown for us in what relates to culture and the debates within US society. As it turns out, third-wave capitalism had already proposed that education in schools should be eliminated, that there should be a shift towards education at home. To give you an example, in 2015, the Interamerican Development Bank proposed that a model of education-at-home should be implemented in the continent.

This is what we call a “global pedagogic blackout,” and we warned about its danger in 2016 and 2017.

To give you another example, for years prior to her appointment as US secretary of education, Betsy DeBos had been arguing for cutting back funding for schools and teacher formation because, according to her, virtual classrooms would allow a shift to an at-home system that would strengthen US values.

In other words, global capital’s intention to impose homeschooling is evident. We have been warning of this danger. Now, the COVID-19 pandemic made it a convenient imperative to shift away from schools. The virtual education-at-home agenda imposed itself and we are complying.

This is very dangerous since 99.9% of virtual educational contents are in private hands. Google Education, Pearson Education, and Discovery Education are knowledge transnationals that basically own the virtual education-at-home model. Countries in Latin America, including Venezuela, didn’t prepare for this. We can call this a global crisis of educational sovereignty, which is all the more dangerous in a country that proposes to transition to a new social model.

Hugo Chavez and two children who received the canaimita computer. (MinCI)

The blockade and sanctions affect all aspects of life, including the educational system. Further, there is a social debt with teachers in Venezuela, whose salaries often fail to cover the cost of the transportation to school. How can this be solved in a country that continues to be besieged, and in which we must seek creative and popular solutions to the problems we face?

The US’ criminal blockade affects not only the economy but also daily life for the population, including, of course, education. There are two ways to solve this problem. One is to make a pact with the bourgeoisie, and the other one is to rekindle the socialist project by pushing forward anti-capitalist measures. I advocate for the second option, and this is not an “ultra-leftist” attitude.

For example, 2018 World Bank data show the Venezuelan debt to be around 150% of its GDP. Two years later, international debt seems to be above 200%. Anti-capitalist solutions are not utopian proposals that might only be carried out without sanctions. For instance, we could refuse our external debt. It is not really possible to pay our debt unless we surrender our assets here in Venezuela as payment to capital. To say the obvious, that can be equated with giving up sovereignty and independence.

As I see it, the blockade gives us the opportunity to push socialist policies forward.

I visited Cuba during the special period, and one of the things that most impacted me was how the people in the government and party leadership lived. The leadership lived just as the common people lived. I think it is very important for us to highlight this in our current situation. We should learn from Cuba: when the blockade hit them hard, the leadership didn’t turn over the nation’s assets. Instead, they sacrificed themselves with the pueblo, and they channeled a great deal of their very limited resources to education.

Regarding teachers’ salaries, capitalism likes to present teachers as people with extraordinary vocations. That is how the system tries to justify overexploitation. Instead, we have always defended the idea that we are education workers, and as workers, we deserve a dignified salary in the working world.

A teacher’s salary today is outrageously low, but in fact, this is not new. We were already concerned about teachers’ wages having lost their purchasing power in 2009! Also, compensation should be holistic: teachers need computers… and internet connections… We cannot have one discourse for the outside world and one for the internal one. We support the teacher’s strike in Bolivia when they criticize the government because it is outsourcing the cost of computers and internet onto teachers. However, if we criticize the situation in Bolivia, we have to be coherent and be critical here too!

Even before the financial sanctions began in 2017, there was already a serious problem with student attrition. The sanctions seem to have accelerated the drop-out rate. Is there any good data about this?

No, there are no numbers available and that is a very serious problem. Like many others, I have been demanding that the state release data in general, and particularly regarding dropout rates. It is not possible to solve problems if we don’t understand the dimensions of the crisis we are facing. Recently the UCAB [Andres Bello Catholic University], hand-in-hand with the UN, produced a report with dramatic numbers. Are they correct or not? We can only guess…

The state stopped publishing school data around 2013. By now, nobody who has been near a school can have any doubts. Empirical evidence points to a dramatic dropout rate. There are many reasons for this, ranging from teachers abandoning their posts (due to their low wages and problems with transportation) to problems with electricity and general infrastructure. On top of that, there are important problems with the PAE [“Programa de Alimentacion Escolar,” school meal program]. For a while, almost 100% of public school children received their meals in school, but that has changed dramatically.

To address this situation, we first have to understand where we are. We need the data to be released. This is not a problem of faith or discourse. This is an education crisis, and we need access to the numbers so that we can look for solutions.

You have reflected on the students «disappeared» from education in the context of the COVID-19 lockdown. Internet access in Venezuelan households, as in much of our continent, is below 50 percent. How does the current emphasis on education-at-home affect the different social classes?

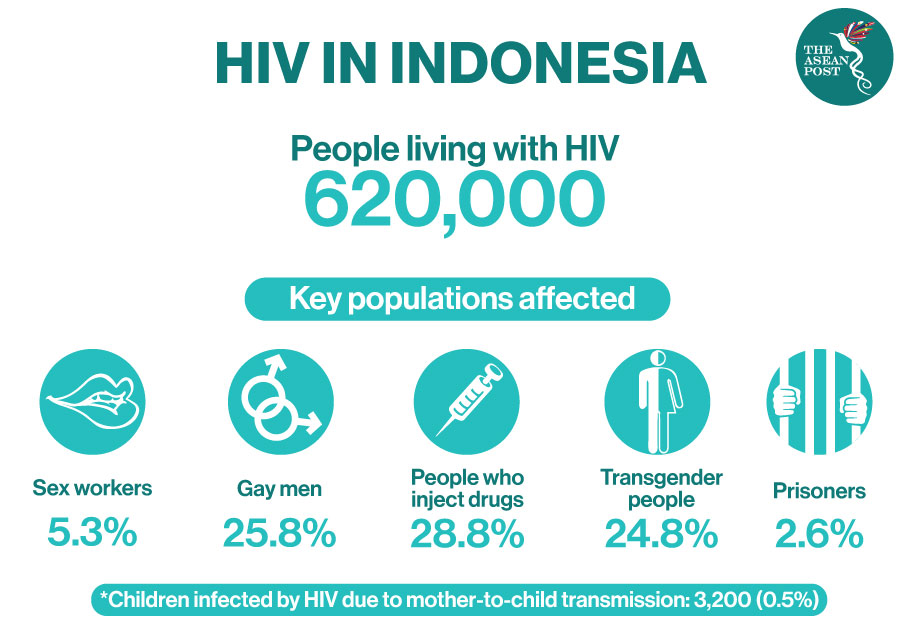

Indeed, some 50% of students around the world have technological barriers to access that cannot be overcome overnight. In April, the director of UNESCO Audrey Azoulay said that of the 1.37 billion children and teens out of school due to the pandemic, 800 million don’t have access to a computer, and 700 million don’t have access to the internet. This represents a global “educational blackout.”

All of this holds for Latin America. Ecuadorian teachers are demanding the destitution of the education minister because 70 percent of children are falling by the wayside. In Bolivia, there is a teachers’ hunger strike because more than 80 percent of the students don’t have access to the tools needed to study from home. The SENA [Colombia’s national education system] declared that of the more than 800,000 children in school in February, 528,000 have effectively dropped out. Venezuela is part of this whole picture. Our situation is critical, and anybody who is teaching in Venezuela can attest to this. We cannot be solidarious with teachers struggling in the continent while turning a blind eye toward our own problems.

In fact, these are not times for celebrating. Chavez taught us that our main concern should be for those who are left outside. With this in mind, let’s take a critical look at the concept of “school at home” and “university at home.” Neoliberalism coined these terms with its desire to transfer the responsibility of the state to families.

When the lockdown set in, I pointed out that hundreds of thousands of children would not have the tools to continue studying and this was taken as an attack… Again, this goes back to the left’s fear of debate. We shouldn’t unlearn what we learned from Chavez: we can have 99 children in school, but if one is missing, that one kid should be a concern to revolutionaries.

It is true that the work of teachers is extraordinary. They are sacrificing themselves in order to go on teaching. That should be recognized. Nonetheless, our main concern should be the thousands of children who are falling by the wayside.

Those of us who continue to teach, we know that at the very least half of our students are unable to keep up. I say that with the aim of awakening concern. I think, for instance, that Robinson, Ribas, and Sucre Missions should be going house by house, to figure out who has access to technology and who does not.

Again, teachers and university professors deserve recognition and dignified salaries. They have been bearing the brunt of the crisis on their shoulders. What they are doing is marvelous and it shows that they have energy and commitment. In many cases, teachers are doing what the state should be doing… Their self-sacrifice should be celebrated, but that is not enough.

The truth is revolutionary if we talk about problems and look for real solutions for the people. We have to understand how things really are, and we have to develop a plan to reach the people. We cannot be ostriches, sticking our heads in the ground to avoid seeing problems. We have to face reality as it is.

There are ways to solve our problems, but we need to have a debate. Unfortunately in the left we have a culture that interprets debate as giving ammunition to the enemy. Let’s remember Chavez, who was most concerned by those left behind by the system and also Che Guevara who said, “Truth is the most revolutionary act that we can engage in.”

Akaiz Zambrano receives her Sucre Mission university diploma. (YVKE)

Note

[*] Simon Rodriguez (1769-1854) was the teacher of Simon Bolivar and a creative independence era pedagogue. Andres Bello (1781-1865) was a linguist with a classist conception of the world. Cecilio Acosta (1818-1881) was a liberal reformer. Luis Beltran Prieto Figueroa (1902-1993) was an education reformer who implemented the technical education system in Venezuela.

Users Today : 102

Users Today : 102 Total Users : 35459568

Total Users : 35459568 Views Today : 161

Views Today : 161 Total views : 3417919

Total views : 3417919