Author: Silvia Peirolo

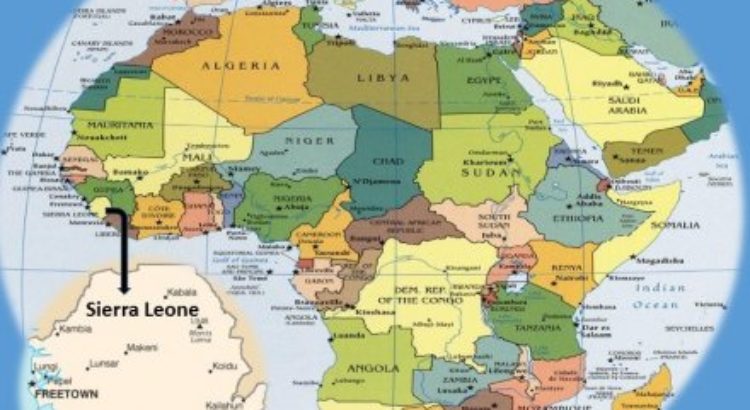

La Sierra Leone è un piccolo paese nell’Africa occidentale conosciuto per grandi (drammatiche) storie: tratta degli schiavi, guerra dei diamanti, Ebola. Nonostante le ingenti somme ricevute dalla comunità internazionale, la Sierra Leone rimane uno dei paesi più poveri del mondo. Nel 2017, l’Italia ha ricevuto 1101 richieste di protezione internazionale da cittadini sierraleonesi di cui 253 sono state rifiutate. Date le condizioni nel paese, il conferimento dello status di ‘rifugiato’ ai cittadini sierraleonesi – ferma restando la valutazione individuale nel merito di ogni domanda d’asilo – non è più giustificato. Ciononostante, le condizioni di fragilità e di vulnerabilità dei cittadini sierraleonesi permangono tutt’oggi. Qual è il ruolo dell’Unione Europea, e dell’Italia, di fronte alle richieste di solidarietà avanzate da persone non ‘perseguitate’ nel senso stretto del termine, ma in condizioni di estrema fragilità e vulnerabilità? Alcuni potrebbero chiedersi: perché l’Unione Europea si dovrebbe interessare alla Sierra Leone? Ci sono 4513 km in linea d’aria che separano la Sierra Leone all’Italia, non sono sufficienti per ignorare i ‘loro’ problemi? Eppure, nel passato, la futura Unione Europea si è interessata molto alla Sierra Leone, prima per la tratta degli schiavi e poi per le risorse naturali.

Le conseguenze della tratta degli schiavi

Le prime navi portoghesi iniziarono a visitare regolarmente il paese intorno al 1460. L’estuario di Freetown era considerato uno dei pochi porti ‘buoni’ della costa occidentale dell’Africa: vennero così costruiti imponenti scali commerciali lungo la costa e gli europei cominciarono a comprare una merce che nei secoli successivi sarebbe rimasta la più preziosa di tutti: gli schiavi. La tratta degli schiavi non fu, come molti pensano, un invenzione degli europei: esisteva già e rimarrà un’attività importante in Sierra Leone fino alla metà del 19° secolo.

La Sierra Leone esportava moltissimi schiavi. Bunce Island è un’isola che si trova a circa 32 chilometri da Freetown. Sebbene sia molto piccola, grazie alla sua posizione strategica al limite della navigazione per le navi oceaniche, è una base ideale per la tratta degli schiavi. Decine di migliaia di africani furono esportati da Bunce Island verso le colonie nordamericane della Carlona del Sud e della Georgia e sono gli antenati di molti afroamericani degli Stati Uniti.

- Mappa di Bunce Island

Fonte: www.yale.edu, hitchcock.itc.virginia.edu

Bunce Island è il simbolo di un periodo in cui la Sierra Leone si trasformò in una gigantesca riserva per la caccia all’uomo. Sono stati fatti studi interessanti per capire l’impatto della schiavitù sui paesi africani. L’economista Nathan Nunn, dall’università statunitense di Harvard, sostiene che i territori da cui un tempo proveniva la maggioranza degli schiavi sono ancora oggi i più poveri e violenti. Eppure la tratta degli schiavi è stata abolita ormai più di duecento anni fa, com’è possibile?

Nel 17° secolo all’imperialismo portoghese si sostituì quello britannico. Gli inglesi presero il controllo del paese, fondando nel 1787 la Colonia della Corona Britannica della Sierra Leone, con Freetown come capitale. Il nome ‘Freetown’ (città libera) è ben augurante e voleva essere l’incarnazione della speranza nel futuro di chi era potuto tornare in patria come uomo libero. La capitale sierraleonese venne infatti fondata come un insediamento per gli schiavi che si erano schierati con gli inglesi durante la guerra rivoluzionaria americana. Diventò quindi la destinazione degli schiavi liberati fino al 1885. Anche se originariamente gli schiavi provenivano da tutte le aree dell’Africa, la maggior parte decise di rimanere in Sierra Leone. I discendenti degli schiavi liberati sono quelli che oggi vengono definiti creoli.

La maledizione delle materie prime

Nell’ottocento gli europei costruirono gli imperi coloniali in Africa. Le stive delle navi commerciali non si riempivano più di giovani schiavi, ma di cacao, avorio, caucciù e olio di palma. I commercianti europei dividevano i profitti con un élite africana che era responsabile del controllo del territorio africano. In Sierra Leone, gli inglesi si espansero nell’entroterra promuovendo il commercio e stipulando trattati con capi indigeni. Quando il comportamento dei capi africani non era conforme ai dettami inglesi, intervenivano l’esercito e la marina. Le stesse forze di polizia della Sierra Leone furono fondate nel 1829 dai britannici con l’obiettivo di proteggere gli interessi coloniali. In un certo senso era cambiata la materia prima del commercio ma le dinamiche erano rimaste immutate: questo modello ha caratterizzato il paese anche dopo la fine del dominio coloniale, e persino dopo la conquista dell’indipendenza nel 1961.

Sull’Africa grava una maledizione delle materie prime che si passa di generazione in generazione. Richard Auty nel 1993 usò per la prima volta l’espressione ‘maledizione delle risorse’ per descrivere come i paesi africani, ricchi di risorse naturali, abbiano paradossalmente una crescita economica minore rispetto ai paesi privi di abbondanti risorse naturali. L’idea che le risorse naturali possono essere economicamente più una maledizione che una benedizione lo dimostra la sanguinosa guerra dei diamanti.

L’estrazione e la vendita dei cosiddetti diamanti insanguinati possono facilmente essere descritti come un fattore prolungante della guerra civile protrattasi tra il 1991 e il 2002, come mostra il film Blood Diamonds. Dopo l’indipendenza nel 1961, il nuovo apparato politico sierraleonese si dimostrò debole e incapace di fornire gli elementi necessari al benessere e alla crescita economica e sociale della popolazione, cosicché, quando la guerra civile esplose nel 1991, molti giovani insoddisfatti avevano trovato comprensione nel RUF, il Fronte Rivoluzionario Unito. In questa guerra civile in cui tutti combattono contro tutti, tutti vogliono quei diamanti, che si vendono molto bene negli Stati Uniti e in Europa. Quando ci si trovava a parlare con i mercanti di diamanti nei bar degli hotel per ‘opotu’ (bianchi nella lingua indigena), i commercianti dicevano che trattavano in ‘meloni e banane’. Si riferivano al colore dei diamanti grezzi.

- I lavoratori lavorano alla ricerca di diamanti in una miniera gestita dal governo in Sierra Leone. Photo credit: CNN

Leggi anche: https://money.howstuffworks.com/african-diamond-trade2.htm

Nel 1999, nel tentativo di promuovere i negoziati tra il RUF e il governo venne firmato l’Accordo di pace di Lomé. L’accordo mirava a portare la pace assicurando a RUF un’amnistia generale e offrendo posizioni governative ai comandanti. Per esempio, al comandante del RUF venne proposta la vicepresidenza e il controllo delle miniere di diamanti del paese, in cambio della cessazione dei combattimenti.

Il 19 gennaio 2002, il presidente dichiarò: “war don don”: la guerra è finita. Il bilancio è tragico. 2,6 milioni di sfollati, 50.000 morti, 257.000 vittime di abusi sessuali, 250.000 bambini soldato, 11 capi di accusa per l’ex-Presidente della Liberia, 17.000 caschi blu inviati sotto la cosiddetta “politica di riconciliazione nazionale”. Ishmael Beah, ex-bambino soldato diventato celebre scrittore di Memorie di un soldato bambino, ha avuto l’incredibile fortuna di sfuggire alla guerra dei bambini e, dopo essersi trasferito negli Stati Uniti, ha raccontato la sua storia. Eppure la guerra non ha colpito solo la generazione di Ishmael. Le vittime della guerra non sono solo quelle uccise o mutilate durante il conflitto, ma anche le successive generazioni che vivono sulla propria pelle le terribili condizioni della ricostruzione. La guerra ha avuto un impatto significativo sull’economia, sulla governance, sulla società civile, sull’ambiente, sulla salute e sul sistema educativo, i cui risultati si vedono ancora oggi.

I rifugiati sierraleonesi: da dopo la guerra ad oggi

La guerra civile ha costretto alla fuga circa due milioni di persone, soprattutto in Guinea e in Liberia. Con il ritorno degli ultimi dei circa 280mila rifugiati sierraleonesi rimpatriati dalla fine della guerra civile, si è concluso nel luglio 2004 l’imponente programma di rimpatrio dell’Alto Commissariato delle Nazioni Unite per i Rifugiati (UNHCR). Sempre secondo l’UNHCR, nel 2008, le condizioni in Sierra Leone erano tornate alla normalità. Di conseguenza, l’UNHCR ha consigliato agli stati di non concedere più lo status di rifugiato ai cittadini sierraleonesi – ferma restando la valutazione individuale nel merito di ogni domanda d’asilo – poiché le cause che avevano portato all’attribuzione di tale status in passato hanno cessato di esistere. Considerando i cambiamenti importanti e permanenti avvenuti nel paese, il conferimento dello status di ‘rifugiato’ ai cittadini sierraleonesi non è più giustificato.

Il grafico rappresenta l’andamento delle domande di asilo da parte di cittadini della Sierra Leone dal 2000 al 2017. La prima riga azzurra rappresenta il numero totale di domande di asilo. In verde è indicato il numero di richieste accettate e in rosso le domande respinte. È chiaro da subito che le domande di asilo si sono drasticamente ridotte dal 2001, per poi leggermente aumentare negli ultimi anni.

- Domande di asilo da cittadini della Sierra Leone dal 2000 al 2017

Fonte: https://www.worlddata.info/africa/sierra-leone/asylum.php

In Italia, nel 2017, 1.101 cittadini sierraleonesi hanno richiesto protezione internazionale. 23 domande sono state accettate, 253 rifiutate. Delle altre 825 domande di asilo non si sa ancora nulla. Tralasciando l’assurdità della lentezza dei procedimenti che lasciano la vita di 825 persone in sospeso per mesi, quelle 253 domande di asilo rifiutate aprono una riflessione. Paolo Naso, docente di Scienza politica all’Università Sapienza di Roma, sostiene che i ‘migranti’ che arrivano oggi in Italia, non sono né migranti economici né rifugiati politici, ma entrambe le cose. La distinzione tra richiedente asilo e migrante economico appartiene ad un periodo storico passato, quello del muro di Berlino e della guerra fredda. Il rifugiato era perseguitato a livello individuale, come ad esempio un dissidente anti-comunista.

Nell’epoca attuale le persecuzioni sono più collettive, sono fatti di massa: dalla crisi ambientale, alla povertà economica, al cosiddetto state failure. Oggi dividere i due aspetti è impossibile. Da qui la debolezza delle politiche che semplicisticamente affermano: “sì ai rifugiati politici, no ai migranti economici”.

I sierra leonesi che richiedono protezione internazionale in Italia riflettono perfettamente questo concetto. La Sierra Leone ha storicamente affrontato episodi di violenza e di conflitto, con una decennale guerra civile che ha distrutto il paese. Eppure, oggi c’è qualcosa che uccide tanto quanto le guerre e le epidemie: la povertà. In Sierra Leone – 181esima su 186 posti nella graduatoria dell’indice di sviluppo umano delle Nazioni Unite – il 57% della popolazione vive con poco più di un dollaro al giorno, l’aspettativa di vita è di 50 anni, 161 bambini su 1.000 muoiono prima di raggiungere i 5 anni di età e 1 donna su 100 muore partorendo. Oggi la dimensione della persecuzione, della sofferenza, s’intreccia con quella della povertà.

Considerazioni conclusive

Quello che serve oggi all’Unione Europea non solo nuove politiche di respingimento o di accoglienza-integrazione dei migranti, non sono dibattiti sulla condizione di solidarietà tra gli Stati membri sul piano finanziario o sulla redistribuzione dei migranti e delle loro famiglie secondo precisi standard.

La domanda che dovremmo porci è: Quale potrebbe e dovrebbe essere la risposta dell’Unione Europea alle richieste di solidarietà avanzate da persone in condizioni di estrema fragilità e vulnerabilità?

Le cause di fragilità e vulnerabilità nei paesi di origine non sono un problema ‘loro’, ma un problema ‘nostro’. Quando ci dimentichiamo questo dettaglio, ricordiamoci che è stata la futura Unione Europea ad avere un ruolo centrale nel colonialismo, che ha saccheggiato paesi dalle proprie ricchezze naturali e sottomesso popoli mantenendo dittatori sanguinari. Sono state due potenze alla base dell’Unione Europea a ridisegnare la carta geografica mondiale con gli accordi di Sykes-Picot, inventando stati, e cancellando, prima con una matita e un righello, e poi con le armi, comunità intere. E, se vogliamo guardare ancora più vicino, l’Italia, nel periodo che va dal 1993 al 1997, è stato il principale fornitore di armi leggere ed esplosivi alla Sierra Leone. Secondo i dati del commercio estero Istat, nei primi undici mesi del 1997 sono stati venduti circa 1.600.000 bossoli per fucili.

Abbiamo preso le persone, quando ci faceva comodo. Abbiamo preso le risorse naturali, quando ci faceva comodo. Abbiamo venduto le armi, quando ci faceva comodo. E ora che cosa ci fa comodo?

Silvia Peirolo

Agosto 2018

Fonti consultate:

Baker, B. (2008). Beyond the Tarmac Road: Local Forms of Policing in Sierra Leone & Rwanda. Review of African Political Economy, 35(118), 555-570.

Baker, B., May, R. (2004). Reconstructing Sierra Leone. Commonwealth & Comparative Politics, 42(1), 35-60.

Berghs, M. (2010). Coming to terms with inequality and exploitation in an African state: Researching disability in Sierra Leone. Disability & Society, 25(7), 861-865.

Berghs, M. (2011). Embodiment and emotion in Sierra Leone. Third World Quarterly, 32(8), 1399-1417.

Berghs, M. (2016). War and embodied memory: Becoming disabled in Sierra Leone. Routledge.Berghs, M., & Dos Santos-Zingale, M. (2011). A comparative analysis: everyday experiences of disability in Sierra Leone. Africa Today, 58(2), 18-40.

Boas, M. (2001) Liberia and Sierra-Leone: Dead Ringers? The Logic of Neopatrimonial Rule, Third World Quarterly, Vol. 22, Issue 5, pp. 697 – 723

LA VOCE di Ferrara Comacchio, Aprile 2000, pag.2

Simoncelli, M. (2001) Armi leggere guerre pesanti. Il ruolo dell’Italia nella produzione e nel commercio internazionale, Rubbettino Editore, 190-192

Sull’autrice

Laureata in Scienze Internazionali dello sviluppo e della cooperazione all’Università di Torino (Italia) e in Scienze internazionali con una specializzazione in Aiuto Umanitario all’Università di Wageningen (Paesi Bassi). Si interessa alle questioni legate alla migrazione, ai diritti umani e alla difesa e sicurezza con un focus geografico sull’Africa. Parla fluentemente inglese e francese.

Fuente: http://www.meltingpot.org/Sierra-Leone-Quando-la-dimensione-della-persecuzione-si.html#.W2wz2NJKjMw

Users Today : 15

Users Today : 15 Total Users : 35461023

Total Users : 35461023 Views Today : 33

Views Today : 33 Total views : 3420547

Total views : 3420547