Europe/United Kingdow/21.08.18/Source: www.theguardian.com.

Students to receive results with grades 9-1 after changes initiated by Michael Gove

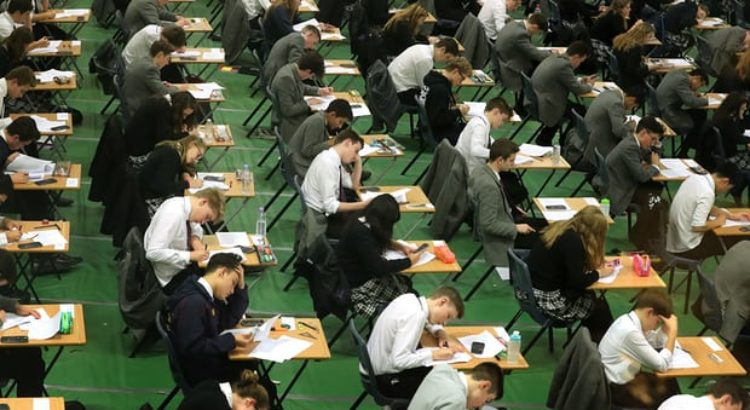

The tougher standards demanded by the new style of GCSEs being awarded for the first time this year have put pupils under a great deal of additional pressure, according to school leaders.

Hundreds of thousands of pupils in England will receive their results this week, with grades from 9 to 1 replacing the familiar A* to G.

Geoff Barton, the general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders, said the “bar has deliberately been set at a higher level” as a result of changes initiated by the former education secretary Michael Gove.

“The new exams are harder, contain more content, and involve sitting more papers,” Barton said. “We are worried about the impact on the mental health and wellbeing of young people caused by these reforms and it is our view that such a substantial set of changes as this should have been introduced in a more managed and considered manner.

“It is to the credit of schools that they have responded to this situation by providing their students with extensive pastoral support in order to alleviate stress and anxiety despite severe funding pressures.”

Hailed as the most significant change in the examination system since O-levels were replaced 30 years ago, the “more demanding, more fulfilling and more stretching” exams were introduced to help the UK better compete internationally, Gove said in 2013.

The fruits of that effort will be seen on Thursday when the results of 20 of the new GCSEs are published, including those in biology, history and Spanish.

Gove’s changes stripped out assessed work that had accounted for a substantial proportion of marks towards the final grades. In chemistry and biology, for example, non-exam assessments accounted for a quarter of a candidate’s marks, but in the new GCSEs everything depends on the final exams.

Assessment remains in some subjects, such as dance and foreign languages, but even then the proportion of non-exam marks awarded has been cut substantially, from 60% to 25% in the case of German and French.

Ofqual, which regulates public examinations in England, has pledged to maintain continuity in the proportion of grades awarded. Cath Jadhav, the director of standards at Ofqual, said exam boards would use statistics to counteract any dip in results caused by teachers being less familiar with the content and pupils having less support material.

“Across all subjects, grade boundaries will be set this summer to ensure that students this summer are treated fairly and are not disadvantaged by being the first to sit new GCSEs,” Jadhav wrote in a blogpost explaining the way grades would be set.

According to Ofqual, the new grade 7 will start at the same standard as the former A grade, meaning 9, 8 and 7 grades replace the old A* and A. The 9 is equivalent to the top half of A* awards, while an 8 encompasses the bottom portion of A* and the top part of an A, making comparisons with the old grades difficult.

“Grade 9 is not the same as the old A* grade. It’s a new grade designed to recognise the very best performance. So in every subject there will be fewer grade 9s awarded than A*s in the old GCSEs,” Jadhav said.

Last year maths, English language and English literature were the firstsubjects to be examined under the new system. About 2,000 pupils gained 9s in all three subjects. As few as 200 pupils have been forecast to achieve a full set of 9s in eight or more subjects this year.

“It was already very hard to achieve the top grade of A* under the old system, and it is even harder to achieve the top grade of a 9 under the new system,” Barton said. “Young people striving for those top grades may therefore feel disappointed if they do not achieve them, even though they have done exceptionally well in the grades they do achieve.”

Because a number of courses, including economics and design and technology, will not offer the reformed exams until next summer, parents will be confronted with children holding a mixture of numbered and lettered grades.

The previous C grade will be fixed to the same boundaries as the new grade 4, but both a 4 and a 5 will be regarded as a pass grade in the same way as a C, with the Department for Education describing a 5 as a “strong pass”.

The new combined science GCSE will be awarded as a double grade, to reflect the greater amount of content being taught. As a result, candidates will be awarded double grades ranging from 9-9, 9-8 and so on, down to the lowest 1-1 grade.

The changes do not affect Wales and Northern Ireland, which are retaining the old GCSE grades. Scottish students sit exams under a separate system.

Source of the notice: https://www.theguardian.com/education/2018/aug/20/new-gcses-put-pupils-under-more-pressure-say-school-leaders

Users Today : 11

Users Today : 11 Total Users : 35460364

Total Users : 35460364 Views Today : 14

Views Today : 14 Total views : 3419114

Total views : 3419114