BANGKOK, 30 de mayo de 2018 –

Resumen: Tomando el ODS 4.2 de la Política a la Acción: Nepal acoge el 3er Foro de Política Regional de Asia y el Pacífico sobre Atención y Educación de la Primera Infancia (AEPI). Desde el primer día de clases, un niño ya podría enfrentar desafíos serios e incluso insuperables para acceder a una educación de calidad. A medida que se abre el 3er Foro de Política Regional de Asia y el Pacífico sobre Atención y Educación de la Primera Infancia (AEPI) y la Conferencia Regional de Desarrollo de la Primera Infancia de Asia y el Pacífico (2018) se abre en Katmandú el 5 de junio de 2018, hay una comprensión creciente de un enfoque multisectorial es esencial para nivelar el campo de juego para los niños, incluso antes de su inscripción en la escuela primaria. El concepto de ‘preparación para la escuela’ es un elemento fundamental de los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible (ODS). Meta 4.2 – ‘Para 2030, garantizar que todas las niñas y niños tengan acceso a un desarrollo, atención y educación preescolar de calidad para que estén listos para la educación primaria. ‘ Cuando los niños no están listos para la escuela para la edad de ingreso primaria, los impactos negativos a largo plazo en los resultados del desarrollo, particularmente para los niños más vulnerables, están bien documentados. Hay teorías bien establecidas y evidencia de investigación que destaca la importancia crítica del desarrollo de la primera infancia, pero 250 millones de niños menores de 5 años en países de ingresos bajos y medios corren el riesgo de no alcanzar su potencial debido al retraso en el crecimiento, la pobreza y la desventaja . Ese potencial abarca el bienestar cognitivo, emocional, social y físico. Esto exige medidas urgentes para aumentar la cobertura de los programas de AEPI de calidad multisectorial que incorporan salud, nutrición, seguridad y protección, atención receptiva y aprendizaje temprano. En el marco del ODS 4.2, se requiere que el Ministerio de Educación (MOE) de cada país desempeñe un papel central en un enfoque multisectorial implementando y monitoreando programas de AEPI de calidad, llegando a otros ministerios y agencias responsables del DIT y coordinando sus esfuerzos. Este enfoque holístico y multisectorial de la AEPI es en realidad un interés fundamental de cada Ministerio de Educación responsable de los resultados educativos de los niños inscritos en el sistema escolar, porque la participación de AEPI está significativamente relacionada con el desarrollo cognitivo y la preparación escolar desde el nacimiento hasta los 8 . Como anfitrión del foro de políticas de ECCE y de la conferencia ECD, Nepal está bien preparado para adoptar este enfoque holístico del desarrollo temprano y la educación. El Primer Ministro de Nepal, Sr. KP Sharma Oli, ha destacado que el desarrollo de la primera infancia está consagrado en la Constitución del país y es esencial para lograr los ambiciosos planes de desarrollo sostenible del país. En ausencia de estos programas ECCE multisectoriales dirigidos por el MOE, los resultados de aprendizaje de los niños sufren, pero también los propios sistemas escolares, ya que pagan el precio si los niños no están bien cuidados con esfuerzos enfocados en su desarrollo antes de llegar a la escuela primaria.

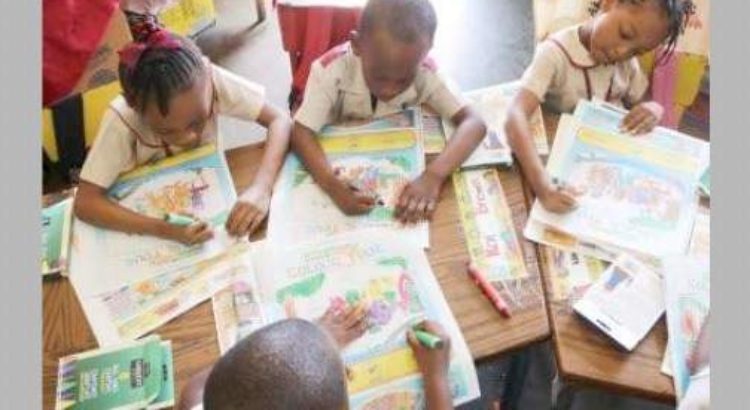

On the very first day of school, a child could already face serious, even insurmountable, challenges to access quality education. As the 3rd Asia-Pacific Regional Policy Forum on Early Childhood Care and Education (ECCE) and 2018 Asia-Pacific Regional Early Childhood Development (ECD) Conference opens in Kathmandu on 5 June 2018, there is a growing understanding that a multi-sectoral approach is essential to level the playing field for children, even prior to their enrolment in primary school.

The concept of ‘school readiness’ is a critical element of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) Target 4.2 – ‘By 2030, ensure that all girls and boys have access to quality early childhood development, care and pre-primary education so that they are ready for primary education.’ When children are not ready for school by the primary entry age, the long-term negative impacts on developmental outcomes, particularly for the most vulnerable children, are well-documented.

There are well-established theories and research evidence highlighting the critical importance of early childhood development, yet 250 million children younger than 5 years of age in low and middle-income countries are at risk of not reaching their potential due to stunting, poverty and disadvantage. That potential encompasses cognitive, emotional, social and physical welfare. This calls for urgent action to increase coverage of multi-sectoral quality ECCE programmes that incorporate health, nutrition, security and safety, responsive caregiving and early learning.

Under the framework of SDG 4.2, each country’s Ministry of Education (MOE) is required to play a pivotal role in a multi-sectoral approach implementing and monitoring quality ECCE programmes by reaching out to other ministries and agencies responsible for ECD and coordinating their efforts. This holistic, multi-sectoral approach to ECCE is actually a fundamental interest of each Ministry of Education responsible for educational outcomes of children enrolled in the school system, because ECCE participation is significantly linked to cognitive development and school readiness from birth to the age of 8.

As the host of the ECCE policy forum and ECD conference, Nepal is well-prepared to adopt this holistic approach to early development and education. Prime Minister of Nepal Mr K.P. Sharma Oli has emphasized that early childhood development is enshrined in the country’s constitution and essential to achieve the country’s ambitious sustainable development plans.

In the absence of these MOE-led, multi-sectoral ECCE programmes, children’s learning outcomes suffer, but so too do school systems themselves as they pay the price if children are not well cared for with focused efforts on their development before they reach primary school.

In addition, there is also an increasing recognition of the importance of systematic monitoring of ECCE efforts, not only to track progress relative to the SDG4.2 indicators – but also because the entire ECCE programme must be seen as a continuum of development.

Since 2013, the UNESCO Asia and Pacific Regional Bureau for Education, UNICEF and ARNEC, with other key partners, have been organizing the Asia-Pacific Regional Policy Forum on ECCE to provide a platform for high-level policy-makers of Asia-Pacific countries to share knowledge and discuss strategies to expand access to, and improve the quality of, comprehensive, integrated and holistic ECCE. The forum will result the Regional Strategy to improve the equity and quality of ECCE.

The 3rd Asia-Pacific Regional Policy Forum on Early Childhood Care and Education (ECCE) is led by UNESCO. The Regional ECD Conference is organized by the Asia-Pacific Regional Network for Early Childhood (ARNEC) www.arnec.net including its core partners United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) Regional Office for East Asia and the Pacific http://www.unicef.org/eapro/ and Regional Office for South Asia andhttp://www.unicef.org/rosa/; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) http://bangkok.unesco.org/; Plan International www.plan-international.org/; Open Society Foundations https://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/; Save the Children www.savethechildren.org and ChildFund Internationalhttps://www.childfund.org/.

The three-day event, being hosted by Nepal Government’s Ministry of Education, Science and Technology, includes the participation of about 700 high-level government officials, development professionals, researchers as well as representatives from organizations working in early childhood development, care and education from 40 countries in the Asia-Pacific region.

For more information, please contact:

Mr Baikuntha Prasad Aryal, Joint Secretary/Spokesperson, Ministry of Education, Science and Technology Email: baikunthaparyal@gmail.com

Ms Kyungah Bang, Programme Officer, UNESCO Bangkok Email: k.bang@unesco.org

Ms Silke Friesendorf, Communication Manager, ARNEC. Email: silke.f@arnec.net www.arnec.net

Fuente: https://bangkok.unesco.org/content/taking-sdg-42-policy-action-nepal-hosts-3rd-asia-pacific-regional-policy-forum-early

Users Today : 61

Users Today : 61 Total Users : 35459527

Total Users : 35459527 Views Today : 89

Views Today : 89 Total views : 3417847

Total views : 3417847