La Consejería de Educación de la Comunidad de Madrid ha cifrado este martes en un 18 % el seguimiento de la huelga convocada por los sindicatos CCOO, ANPE, CSIF y UGT para reivindicar, entre otras cuestiones, mejoras para el profesorado madrileño, como reducción del horario lectivo o mejoras salariales, entre otras cuestiones.

Sin embargo, los sindicatos han elevado el porcentaje de seguimiento de la huelga en la educación pública madrileña a más del 70 %, con mayor incidencia en Secundaria aunque en esta jornada, según los representantes sindicales, destacan el “aumento significativo” en los centros de Infantil y Primaria.

Viciana destaca el desarrollo “con normalidad” de la huelga

La Consejería de Educación ha cifrado en un 18 % el seguimiento de la huelga que, según fuentes del departamento del consejero Emilio Viciana, es inferior a las anteriores: el 8 de mayo fue del 24,5 % y del 21 de mayo del 23,4 %.

En declaraciones a los medios este martes tras participar en un acto, el consejero de Educación, Ciencia y Universidades, Emilio Viciana, ha asegurado que la jornada de huelga “se está desarrollando con total normalidad, no ha habido ningún problema”, con los servicios mínimos “habituales” decretados por la Consejería “en este tipo de circunstancias”.

Servicios mínimos

Los servicios mínimos fijados por la Consejería de Educación establecen que todos los centros educativos deberán contar con el director y el jefe de estudios o el secretario, un maestro por cada 50 alumnos en los centros de Infantil y Primaria, un profesor por cada 90 alumnos en Educación Secundaria Obligatoria (ESO) o ciclos formativos de grado básico y un maestro o profesor por cada 25 alumnos en los centros que atienden a alumnos con necesidades educativas especiales.

La educación de Madrid está llamada a celebrar durante este martes una jornada de huelga convocada por los sindicatos con representación en la mesa sectorial para exigir la reducción del horario lectivo, la libertad de elección de jornada en los centros o la equiparación salarial, entre otras reivindicaciones.

En concreto, piden reducir el horario lectivo a 18 horas en Educación Secundaria, Formación Profesional y Régimen Especial y 23 horas en Infantil y Primaria; a la vez que demandan una reducción de ratios (número de alumnos por aula), los cupos necesarios para la atención a la diversidad y un plan de choque contra la burocracia.

Reunión con el consejero

Tras esta jornada de huelga, este jueves los sindicatos se reunirán con el consejero, quien ha asegurado que se hará “una propuesta” que la Comunidad de Madrid espera “que sea de la satisfacción” de los representantes sindicales.

Esa reunión estaba prevista hace un mes, pero “surgieron unos problemas de agenda” que, según Viciana “impidieron volver a convocarla de manera inmediata”.

Y ha insistido en que se ha estado trabajando en la propuesta, algo que “implica mucho trabajo interno, no solamente de la Consejería de Educación, sino con todo el Gobierno, con las demás consejerías implicadas, sobre todo a la hora de diseñar desde el punto de vista económico, una propuesta que sea responsable, adecuada a las necesidades”.

Viciana no ha adelantado si se atenderá a las reivindicaciones de los sindicatos para reducir las horas lectivas del profesorado madrileño, ya que ha considerado que son los representantes sindicales quienes deben conocer primero la propuesta, al tiempo que ha asegurado que la Consejería tiene “voluntad” de negociar y de ponerse “del lado de los de los profesores”.

Sin embargo, los sindicatos han elevado el porcentaje de seguimiento de la huelga en la educación pública madrileña a más del 70 %, con mayor incidencia en Secundaria aunque en esta jornada, según los representantes sindicales, destacan el “aumento significativo” en los centros de Infantil y Primaria.

Sindicatos celebran el “alto seguimiento” de la huelga, que cifran en un 70 %

Los sindicatos con representación en la mesa sectorial (CCOO, ANPE, CSIF y UGT) han cifrado en más del 70 % el seguimiento de la huelga, con mayor incidencia en Secundaria en esta jornada, si bien han destacado el “aumento significativo” en los centros de Infantil y Primaria.

Además, han subrayado “el alto seguimiento en algunas zonas como Madrid capital, especialmente en los distritos del Sur-Este”, y han resaltado el aumento del seguimiento en el distrito Centro con respecto a las huelgas anteriores.

También han destacado la incidencia de la huelga en la zona Sur, sobre todo en Fuenlabrada y en algunas localidades de la zona Este como Rivas.

Concentración frente a la Consejería

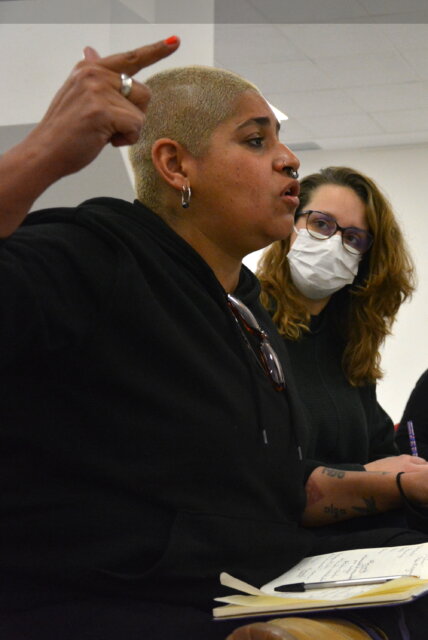

Cientos de profesores madrileños se han concentrado este martes frente a la Consejería de Educación durante la jornada de huelga convocada por los sindicatos CCOO, ANPE, CSIF y UGT por las reivindicaciones que consideran “urgentes” para la educación pública madrileña, como bajadas “reales” de ratios o las mejoras retributivas para los docentes.

Según datos de los convocantes, más de mil profesores se han acercado hasta la calle Alcalá en esta jornada de lluvia a “mojarse” por sus reivindicaciones ante la sede de la Consejería, entre pitos y proclamas por la “educación pública”.

Los sindicatos con representación en la mesa sectorial han llamado a la huelga este martes para exigir la reducción de ratios que sea “real” y del horario lectivo de los docentes, la libertad de elección de jornada en los centros y mejoras salariales, entre otras cuestiones.

En paralelo a esta protesta frente a la Consejería de Educación en la calle Alcalá, se han producido varias concentraciones esta mañana en “todas las localidades grandes de la Comunidad de Madrid”, según ha relatado en declaraciones a los medios la secretaria de Enseñanza de CCOO Madrid, Isabel Galvín, que ha recordado que esta jornada de huelga culminará con una manifestación esta tarde en las calles del centro de Madrid.

La educación en Madrid, llamada hoy a la huelga por el horario lectivo y la bajada de ratios

Users Today : 54

Users Today : 54 Total Users : 35460263

Total Users : 35460263 Views Today : 73

Views Today : 73 Total views : 3418968

Total views : 3418968