Coronavirus: How the lockdown has changed schooling in South Asia

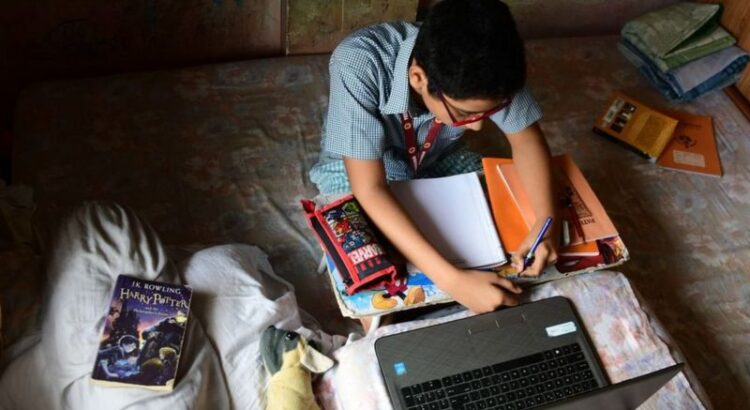

Children across much of Europe have been going back to school for the start of a new year, but in many other parts of the world, coronavirus restrictions have kept classrooms closed.

We’ve taken a look at the situation in India and its neighbours in South Asia where the United Nations estimates nearly 600 million children have been affected by lockdowns.

Who’s not going back to the classroom?

When coronavirus restrictions were first imposed in March and April, it was at the start of the academic year in many South Asian countries.

School classrooms across the region were closed down, and these restrictions have largely remained in place.

Currently:

- In India, classrooms are largely closed, with teaching being done remotely. However, the government says students from grade 9 to 12 can go into schools on a voluntary basis with their parents’ consent from 21 September if they need support

- Bangladesh and Nepal have extended school closures and will continue to rely on remote learning

- Sri Lanka‘s schools reopened in August after trying to reopen in July, but then closing after a spike in cases

- Children in Pakistan will return to school in phases, starting on 15 September as coronavirus case numbers have fallen

Who has access to the internet?

Remote learning involves either live online classes for students, or digital content which can be accessed at any time – offline or online.

But many South Asian countries lack a reliable internet infrastructure and the cost of online access can be prohibitive for poorer communities.

The UN says at least 147 million children are unable to access online or remote learning. In India, only 24% of households have access to the internet, according to a 2019 government survey.

In rural parts of India, the numbers are far lower with only 4% of households having access to the internet.

Bangladesh has better overall connectivity than India. It’s estimated that 60% can get online, although the quality of broadband internet is often very poor.

There is also a lack of basic equipment in many schools.

Nepal’s latest Economic Survey report says that of the nearly 30,000 government schools, fewer than 30% have access to a computer, and only 12% can offer online learning.

Some countries have turned to television and radio for those with no internet-enabled devices or broadband access. These platforms have much greater penetration per head of population.

India’s public broadcaster, Doordarshan, has been broadcasting daily educational content through its television channels and radio services.

Bangladesh’s government broadcaster, Sangsad television, also airs recorded classes on its channels.

«These were among the most successful approaches… in terms of reaching the largest proportion of children,» Jean Gough, Unicef’s South Asia director told the BBC.

Nepal adopted a similar approach, but fewer than half of households have access to cable television.

Opening schools ‘risks infection’

In Sri Lanka, where schools have now reopened, no social distancing is being maintained and only some have made it mandatory to wear a mask, according to Joseph Stalin, general secretary of the Ceylon Teachers’ Union.

Basic safety measures are difficult to implement «as no special funding has been allocated», he told the BBC’s Sinhala service.

The All Pakistan Private Schools Federation has opposed the reopening of schools in September saying they need government funding to help carry out testing and to implement coronavirus safety guidelines.

In India, there are similar concerns about the prospect of schools starting classes again.

«With the reopening of schools, parents, transportation, teachers other service providers will also start functioning and will increase public movement,» Priti Mahara, of Child Rights and You, told the BBC.

There is also a lack of basic equipment in many schools.

Nepal’s latest Economic Survey report says that of the nearly 30,000 government schools, fewer than 30% have access to a computer, and only 12% can offer online learning.

Some countries have turned to television and radio for those with no internet-enabled devices or broadband access. These platforms have much greater penetration per head of population.

India’s public broadcaster, Doordarshan, has been broadcasting daily educational content through its television channels and radio services.

Bangladesh’s government broadcaster, Sangsad television, also airs recorded classes on its channels.

«These were among the most successful approaches… in terms of reaching the largest proportion of children,» Jean Gough, Unicef’s South Asia director told the BBC.

Nepal adopted a similar approach, but fewer than half of households have access to cable television.

Opening schools ‘risks infection’

In Sri Lanka, where schools have now reopened, no social distancing is being maintained and only some have made it mandatory to wear a mask, according to Joseph Stalin, general secretary of the Ceylon Teachers’ Union.

Basic safety measures are difficult to implement «as no special funding has been allocated», he told the BBC’s Sinhala service.

The All Pakistan Private Schools Federation has opposed the reopening of schools in September saying they need government funding to help carry out testing and to implement coronavirus safety guidelines.

In India, there are similar concerns about the prospect of schools starting classes again.

«With the reopening of schools, parents, transportation, teachers other service providers will also start functioning and will increase public movement,» Priti Mahara, of Child Rights and You, told the BBC.

The long period of closure has also led to serious financial shortfalls for those private schools relying on tuition fees.

In Bangladesh, more than a hundred private schools have been put up for sale.

«I have already borrowed money to pay salaries and rent,» Taqbir Ahmed, owner of one such school in Dhaka told BBC Bengali.

Several charities in the region have tried to help the most vulnerable and marginalised schools.

Dr Rukmini Banerji, of the Pratham Education Foundation in India, says: «Efforts have been made by state governments and schools to connect with children who have at least one mobile phone in the household.»

In some cases, students have dropped off the educational roll as the authorities have been unable to establish contact with them.

This could cause the school dropout rate in these countries to rise «exponentially», says Unicef’s Jean Gough, if effective communication isn’t put in place.

«Projections based on previous school shutdowns due to Ebola and other emergencies suggest that there can be very significant losses in terms of learning,» Ms Gough told the BBC.

Additional research by Waliur Rahman Miraj, Muhammad Shahnewaj and Saroj Pathirana

Fuente de la Información: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-south-asia-54009306

Users Today : 5

Users Today : 5 Total Users : 35460268

Total Users : 35460268 Views Today : 6

Views Today : 6 Total views : 3418974

Total views : 3418974