China/Agosto de 2017/Fuente: The News Lens

Resumen: Las lágrimas brotaron en los ojos de Luo Maoling mientras se dirigía a la pequeña multitud en la ceremonia de clausura del campamento de verano. Más de 70 donantes de largo plazo de la Fundación Adream habían llegado a la ciudad de Barkam, sus familias en remolque, para participar en el campamento de cuatro días. Ahora, el jefe adjunto de la autoridad educativa local, Luo ha sido testigo del arco de la fundación caritativa desde su programa piloto lanzado en la ciudad de alrededor de 55.000 hace una década. «Me avergonzaba de que no hubiéramos puesto en práctica bien el programa», dijo. «Podríamos haber hecho un mejor trabajo haciéndonos dignos de todas estas donaciones». Barkam está situado en las montañas de la provincia de Sichuan en el suroeste de China. Su población es predominantemente poblada por tibetanos, aunque los residentes están bastante dispersos: La ciudad ocupa un área aproximadamente del tamaño de Shanghai, pero alberga alrededor del 0,2 por ciento de la población de la ciudad más grande. Cuando un terremoto de 8.0 grados de magnitud devastó la provincia en 2008, Barkam fue sobre todo salvado. De los estimados 87.600 que murieron, el terremoto sólo cobró ocho vidas de Barkam, que estaba a sólo unas horas de viaje desde el epicentro, pero protegido por una cresta de la montaña. Tres meses antes del terremoto, Adream abrió su primer «Centro de los Sueños», una especie de sala de lectura de alta tecnología para los jóvenes estudiantes de Barkam.

Tears welled up in Luo Maoling’s eyes as he addressed the small crowd at the summer camp’s closing ceremony. Over 70 longtime donors to the Adream Foundation had come to the city of Barkam, their families in tow, to participate in the four-day camp. Now the deputy head of the local education authority, Luo has witnessed the charitable foundation’s arc since its pilot program launched in the city of around 55,000 a decade ago.

“I was ashamed that we had not implemented the program well,” he said. “We could have done a better job of making ourselves worthy of all these donations.”

Barkam is nestled in the mountains of Sichuan province in southwestern China. It’s predominantly populated by Tibetans, though residents are fairly spread out: The city occupies an area roughly the size of Shanghai but is home to about 0.2 percent of the larger city’s population. When an 8.0-magnitude earthquake devastated the province in 2008, Barkam was mostly spared. Of the estimated 87,600 who died, the quake claimed just eight lives from Barkam, which was only a few hours’ drive from the epicenter but protected by a mountain ridge. Three months before the earthquake, Adream opened its first “Dream Center,” a sort of high-tech reading room for Barkam’s young students.

A decade later, you can still see signs of the earthquake in the mountains lining the raging, lead-colored rivers that snake through that part of the province. Since its founding, Adream has expanded from a single pilot project to 15 schools in the area and countless others across China, contributing the equivalent of 3 million yuan (US$446,000) in educational resources — classroom materials, teacher trainings, and online tech support — to the local school system. From its humble beginnings in Barkam, Adream has grown into one of the most influential education charities in China, serving 3 million underprivileged students with 2,600 Dream Centers, mostly in China’s oft-neglected heartland. Though the idea for Adream was conceived in Hong Kong and they are now headquartered in Shanghai, Barkam was ground zero.

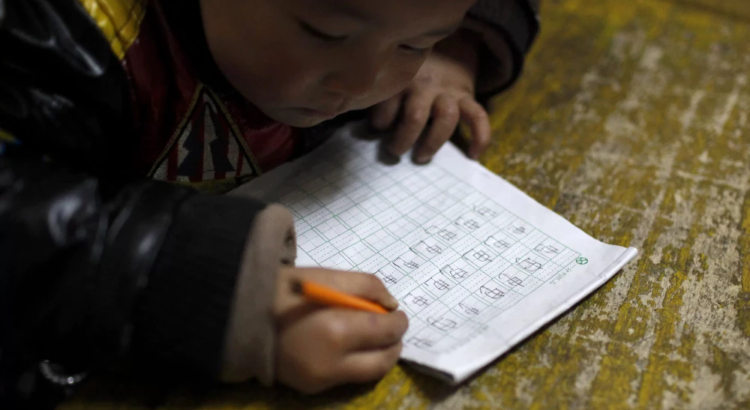

In contrast to the philanthropic group’s rampant growth, Barkam itself has stayed more or less the same since the first Dream Center opened. Special instructors at the city’s partner schools are still holding Dream Classes for faculty, as they have for years. Serving as a sort of testing ground for creative teaching methods, these classes are a far cry from the rote learning methodology embraced by many schools in China. Yet because teachers are so often evaluated according to their students’ test scores, many of the Dream Teachers were given the cold shoulder by their peers, who saw little incentive to introduce change in their classrooms. And even if the faculty had been more receptive to the Dream Teachers, having just one per school was rarely enough to make a splash.

Beginning in 2015, Deputy Director Luo managed to transfer the few talented Dream Teachers working in the countryside into schools in downtown Barkam — up the professional ranks, for all intents and purposes. But by that time, most of Barkam’s Dream Teachers had become discouraged and quit. Only 13 remained. The high dropout rate made the program difficult to sustain in Barkam: Despite being Adream’s home base, the city was no beacon of success for other Dream programs to emulate.

Barkam No. 2 Middle School, the program’s flagship institution, saw seven Dream Teachers resign and its Dream Center nearly dismantled. Today, however, the school has a rising star in 26-year-old Cai Wenjun. Expressive, upbeat, and charming, Cai is often invited to travel to far-flung places such as Xinjiang and Inner Mongolia to train cohorts of China’s 60,000 Dream Teachers, who come from all walks of life and from partner schools all over the country.

China is a notoriously top-down society. For nonprofit and for-profit businesses alike, relationships with the authorities can spell doom or boom — and Adream has understood this since day one. The fact that Barkam’s Party secretary, Zhang Peiyun, and the head of the local education bureau, Liu Rongxin, attended the summer camp’s opening and closing ceremonies, respectively, speaks volumes about the guanxi — interpersonal relationships that facilitate business and other dealings — that the foundation has managed to cultivate in official circles. In fact, the charity counts at least one local government among its donors: In exchange for financial support from Zunyi, a city in southwestern China’s Guizhou province, the organization will introduce Dream Centers at all of the city’s public schools.

With nearly 3,000 Dream Centers now open to students, Adream is hungry for funding to cover both its current overhead costs and its plans for future expansion. So far, increased attention from government bodies has proved beneficial in helping the organization gain funding and an official vote of confidence — along with all the public credibility and influence that carries.

Out in the audience at the camp’s closing ceremony, Zhuokeji Primary School’s headmaster, Yan Bo, is less concerned about Dream Teachers needing training and Dream Centers needing refurbishing. Instead, he’s worried about the very survival of his school. It’s well-run and has a beautiful campus, but at 10 kilometers from the city center, it has trouble retaining students, who are leaving in droves for more central alternatives believed to have more resources at their disposal.

Urbanization is taking a mounting toll on rural schools, and Barkam is no exception. Zhuokeji Primary School was designed for 300 students but currently accommodates just 80. Sure to accelerate what until now has been a steady decline is the fact that just 4 kilometers away, the local government has built a massive new school for over a thousand students. Rumored to have topflight teachers and better facilities, Barkam No. 4 Primary School will open its doors this fall — and may soon force Zhuokeji to shutter its own.

Even after a decade of innovation and hope for Barkam’s schools, deputy education chief Luo has seen three of his young relatives settle down in Shanghai for work. But he understands their decisions: To him, true education stems from an awareness of the wider world — a world the Adream Foundation has opened up to the children of Barkam — and from pursuing the chance to roam and experience new things while we’re still young, willing, and able.

Fuente: https://international.thenewslens.com/article/75265

Users Today : 257

Users Today : 257 Total Users : 35459852

Total Users : 35459852 Views Today : 430

Views Today : 430 Total views : 3418402

Total views : 3418402