Australia/ 2 de junio de 2016,/By panadero de Sally , and Georgina Ramsay

Resumen: Existe un estudio donde se plantea la necesidad adaptar los estilos de aprendizaje para a aquellos cuyo primer idioma no es el Inglés. Entre tanto dice: Peter Dutton, el Ministro de Inmigración y protección de las fronteras, en los titulares recientemente después afirmando que muchos refugiados son analfabetas. No sólo es esta declaración de las estadísticas no fiables, que no tiene en cuenta las complejas cuestiones de por qué los estudiantes – y no sólo los que proceden de refugiados – pueden tener dificultades con la lectura y la escritura. Señalan la experiencia educativa de los refugiados en Australia .Aceptan que la mayoría de los refugiados reasentados en Australia sabe leer y escribir en su propio idioma. En línea con estas aspiraciones, muchas universidades han estado preparando para el aumento de la matrícula de estudiantes de origen de los refugiados. ¿los estudiantes de un fondo de refugiados experimentan dificultades particulares al llevar a cabo los estudios universitarios? se refieren a la barreras para el aprendizaje se necesita comprender a los estudiantes de familias de refugiados -, así como los que no son , la investigación muestra que los estudiantes de familias de habla no-Inglés aprenden de manera diferente dependiendo de los tipos y el número de idiomas que hablan y saben leer y escribir en su propio idioma. Los estudiantes internacionales que han aprendido inglés antes de vivir en otro país de habla inglés son más propensos al aprendizaje auditivo y visual. Estos estudiantes han aprendido inglés predominantemente a través de los textos. Esto significa que sus conocimientos, en cuanto a la lectura y la escritura, es generalmente más desarrollada que su hablar y escuchar. Se refieren que al Apoyar a los estudiantes en el aula y un maestro con estrategias para el aula deben incluir: Llegar a conocer a los estudiantes y ver qué experiencias y estilos de aprendizaje así como los enfoques reconocer que la educación no tiene por qué limitarse a la alfabetización formal.

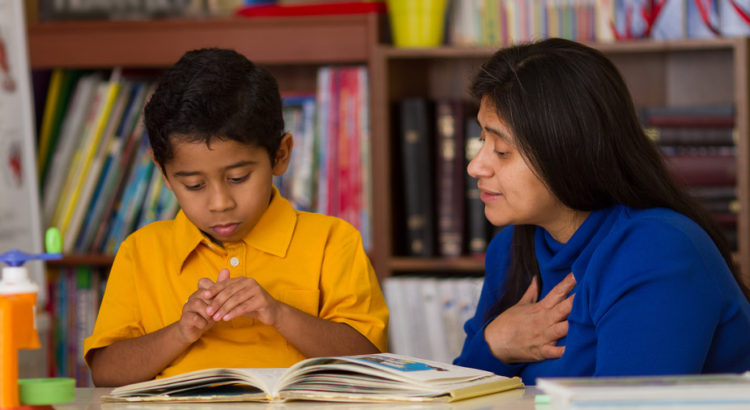

We need to adapt learning styles to suit those whose first language isn’t English. from www.shutterstock.com

Peter Dutton, the minister for immigration and border protection, made headlines recently after claiming that many refugees are illiterate.

Not only is this statement a misleading appropriation of statistics, it fails to address the complex issues of why students — and not just those from refugee backgrounds — may struggle with reading and writing.

Educational experience of refugees in Australia

We know that the majority of refugees who are resettled in Australia are literate in their own language.

Data based on refugees who’ve resettled in the previous three to six months shows that around 77% of female refugees are literate in their own language, along with 83% of male refugees.

It found that 66% of refugees said they plan to study further and 30% aspire to achieve a university degree.

A longitudinal survey of immigrants who entered Australia on a humanitarian visa in 1999/2000 showed that 33% of them had tertiary qualifications.

Those from Afghanistan (64%) and Sudan (47%) were most likely to have achieved a tertiary qualification.

Data from the 2006 census show that almost 60% of second-generation humanitarian entrants attained post-school qualifications, which is 10% greater than the figure for those born in Australia.

In line with these aspirations, many universities have been preparing for increasing enrolments of students from a refugee background.

But do students from a refugee background experience particular challenges when undertaking university study?

Barriers to learning

It is not just literacy that has impacts on the experiences of students from a refugee background.

Different educational systems, cultural and societal values, and general unfamiliarity in the new country of settlement all present challenges.

Despite these barriers, refugees are not a specific equity group and are often treated as mainstream students. Their diverse educational experiences and learning styles can consequently be ignored or misunderstood.

We need to better understand the ways that students from refugee backgrounds – as well as broader cohorts of students from non-English-speaking backgrounds – learn.

“Eye” and “ear” learners

Research shows that students from non-English-speaking backgrounds learn differently depending on the types and number of languages they speak and are literate in.

For example, international students who have learned English prior to living in an English-speaking country are more likely to be “eye” learners.

These students will have learned English predominantly through texts. This means that their literacy, in terms of reading and writing, is generally more developed than their speaking and listening.

As “eye” learners, these students are likely to be successful according to conventional methods of teaching in Australia that privilege text-based evaluation.

Students from a refugee background predominantly become literate in English in Australia as a second (or third or fourth etc) language. This includes refugees born overseas and their children, who often receive the bulk of their education in Australia.

These students are more likely to be “ear” learners, who pick up language through daily interaction, rather than text resources.

“Ear” learners are often confident English-language speakers. Yet they often have less-developed literacies, with strong spoken features evident in their academic writing.

Fluency in spoken English for this group of learners can lead to assumptions that ear students are similarly biliterate, but this is rarely the case.

So, how can educational institutions recognise and support diverse learning styles, and avoid reproducing assumptions about the educational history of students from refugee backgrounds?

Supporting students in the classroom

It is important for teachers to go beyond a one-size-fits-all approach to learning. Moving away from reliance on summative assessments based on formal literacies is a good first step. Classroom strategies should include:

- Get to know students and see what experiences and learning styles they can bring to the classroom.

- Move away from assessment items that privilege academic literacies and “eye” learning. Do ten-minute “free writing” sessions, whereby students are encouraged to write down their spontaneous thoughts on a given topic at the beginning of each lesson. This helps to develop familiarity with noting thoughts and opinions in writing, and offers opportunities to gain quick feedback on learning and language. Students could also be encouraged to talk about these pieces with a fellow student, which benefits those who learn by ear.

- Encourage group collaboration. Developing social networks is not only important for inclusion, but is a way for students to enhance academic literacies.

- Embed formative literacy assessments throughout an entire academic term, discussing what counts as good writing and drawing on discipline-specific conventions to teach these. This allows for teachers and students to identify areas for development so that support can be sought before language becomes a problem to be fixed when big assessments loom.

When applied to students from a refugee background, these approaches recognise that education does not have to be limited to formal literacy.

Imagen: https://62e528761d0685343e1c-f3d1b99a743ffa4142d9d7f1978d9686.ssl.cf2.rackcdn.com/files/124447/width926/image-20160530-7709-sa4cvs.jpg

Users Today : 15

Users Today : 15 Total Users : 35460032

Total Users : 35460032 Views Today : 23

Views Today : 23 Total views : 3418654

Total views : 3418654