El docente Mike Thiruman cuenta cómo construyó Singapur uno de los sistemas educativos más exitosos.

Por: Sonia Perilla Santamaria.

En cinco décadas apenas, Singapur pasó de ser una de las naciones más pobres y subdesarrolladas del planeta a una próspera, industrializada y moderna, cuyo exitoso modelo educativo es, sin exagerar, la envidia de todo el mundo.

Desde hace años, sus estudiantes brillan en los primeros puestos de las pruebas internacionales de educación más exigentes, como las Pisa, de la Organización para la Cooperación y el Desarrollo Económicos (Ocde), en las que Colombia y los países latinoamericanos que hacen parte del organismo siguen mostrando pobres resultados.

Precisamente, a la decisión de ese país de apostarle, desde su independencia, en 1965, todo su futuro a la educación de la población, se debe a que hoy sea considerada una nación de avanzada y con bajos niveles de corrupción. No es gratuito que países como Colombia se interesen en su experiencia y busquen reproducirla de algún modo.

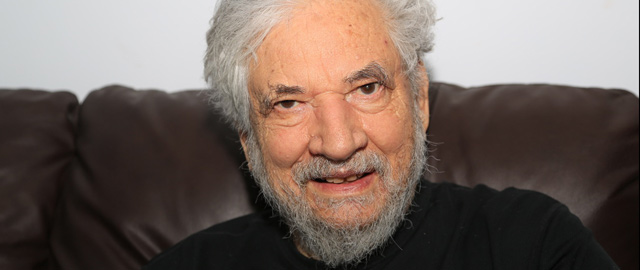

Para hablar del modelo educativo de su país, Mike Thiruman, psicólogo y presidente del Sindicato de Maestros de Singapur, vino recientemente a Colombia, donde participó en el Tercer Congreso para Directivos de Santillana.

Este hombre, de 47 años y que empezó su vida profesional como maestro de primaria, fue invitado por el secretario general de Naciones Unidas, Ban Ki-moon, a formar parte del Grupo Técnico Asesor de la Iniciativa Global de Educación.

¿Cómo describiría el proceso que transformó la educación en Singapur en una de las mejores del mundo?

Pasamos por cuatro fases: una primera, de supervivencia; la segunda fue de eficiencia; la tercera, de formación de habilidades; y ahora estamos en la cuarta: los estudiantes y la educación en valores, incluido el desarrollo del talento de los estudiantes.

¿A qué se refiere con supervivencia?

Cuando logramos nuestra independencia, nos enfocamos en sobrevivir; no tenemos ningún recurso natural importante, y somos una población diversa y multilingüe. Fue una etapa difícil, que se prolongó hasta 1978; en ese periodo nacionalizamos el sistema educativo, y aunque el inglés no es nuestra lengua nativa, decidimos que sería el idioma de instrucción para los estudiantes. También construimos un currículo nacional, enfocado en ciencias y matemáticas. En 1978 hicimos una revisión del sistema educativo, con miras a lograr que los jóvenes permanecieran en la escuela.

¿Tuvieron problemas de deserción?

En esa primera etapa del país la economía estaba saliendo a flote, lo cual abrió muchas plazas de trabajo; no pocos estudiantes decidieron salir de los colegios para vincularse a las empresas, y eso en el largo plazo no era bueno para Singapur, pues no tenían las habilidades necesarias. Buscamos que cada niño estuviera enrolado en el sistema educativo al menos diez años, para que pudiera adquirir competencias básicas en comunicación y numéricas, esenciales para cualquiera trabajo. En 1994 volvimos a analizar el sistema; ya nos habíamos consolidado como nación, ahora podíamos tomar el riesgo de ser un poco más creativos. Seguimos enfocados en habilidades comunicativas y matemáticas, pero nos propusimos promover el desarrollo de la habilidad, del talento, de cada estudiante. Eso nos tomó hasta el 2006, más o menos…

¿Qué vino luego?

Nos dimos cuenta de que el mundo estaba cambiando con la tecnología, la globalización, y el mundo se volvía cada vez más pequeño. Nos planteamos cómo preparar a los estudiantes para competir en un mundo con esas condiciones, y coincidimos en que requerían una serie de habilidades para sobrevivir y ser exitosos en la vida, como las comunicativas, la creatividad, el pensamiento crítico, la curiosidad, la adaptabilidad. Eso es mucho más complicado de enseñar que un contenido; toma mucho tiempo desarrollar estas habilidades.

¿Qué papel cumplieron los profesores en todo ese proceso?

Sin importar qué tan bueno es el sistema educativo o qué tan avanzada es la tecnología, lo importante para todos nosotros siguen siendo las personas. Nos aseguramos de reclutar para nuestro equipo a personas muy competentes como docentes. El secreto del éxito de la educación de Singapur son los maestros. Punto.

¿Qué tipo de estudiantes, de ciudadanos, está formando Singapur?

La idea es que tras 12 años de colegio cada estudiante se convierta en una persona que contribuya activamente a la sociedad, en un ser humano confiable, autónomo y un ciudadano preocupado. Un contribuyente activo piensa en los demás, comparte lo que tiene, siempre.

¿Y qué buscan en los docentes de Singapur?

Para nosotros, los maestros son como un diamante, piedras preciosas con ciertas características importantes: en el centro está la ética en la educación y alrededor, la capacidad de hacer aprendizaje colaborativo, de transformar y transformarse, de ser un líder y un gestor de la sociedad y un profesional competente. Estas son las características de nuestros profesores. Si consideramos que son una gema, los valoramos, los cuidamos y estamos pendientes de que brillen en todo momento.

¿Qué clase de docentes necesita un país como Colombia para transformar la educación?

Necesita a los mejores. En Singapur sufrimos un poco el tema de los docentes cuando la economía estaba ya bien, pues el sector privado pagaba más que el público, y los buenos profesores emigraban para allá; la calidad en el sector oficial bajaba y los sueldos de sus maestros, también. Había que romper ese círculo. El reto de que las personas mejor preparadas sean maestros no es solo nuestro, es mundial. Ante eso teníamos que ser sensibles políticamente hablando, y aunque eso es difícil económicamente, les subimos los salarios a los docentes. Al tiempo, construimos un currículo para que los profesores que no estuvieran en el nivel alto que queríamos pudieran desarrollarlo en las aulas, en un estándar esperado.

El incremento salarial fue para todos, incluidos los maestros que no estaban en un buen nivel…

Sí. A esos docentes en particular, el Ministerio de Educación les dio mucho apoyo en materia de capacitación y entrenamiento, mientras íbamos reclutando a las mejores personas. El salario se les subió a todos, porque no podía haber disparidades si prestaban el mismo servicio. Tomó cuatro o cinco años, más o menos, hasta que cambió también la mentalidad de las personas que hacían parte de ese sistema. Luego, los padres también entraron en esa onda de que si el docente es bueno, invierto, pago. Y solamente eso se produce por el éxito que se evidencia en puntos de referencia internacionales, como las pruebas Pisa.

¿Los papás pagan? ¿Es pública, privada o mixta la educación en su país?

Desde el primer grado hasta el 12, todos los colegios son públicos y financiados por el Estado, y tanto los profesores como los directivos docentes son seleccionados por el Gobierno. Los padres de familia sí pagan un aporte, solo porque queremos que sientan que se les da valor a lo que están recibiendo. Muchas veces, cuando las cosas son completamente gratuitas, la gente no les da el debido valor.

¿Cómo lograr que las prácticas de aula sean atractivas y motivadoras y no aburran a los estudiantes?

Eso no solo pasa solo en Colombia, también es un fenómeno global. Mientras los espacios de trabajo se han transformado y adecuado a los cambios del mundo, los salones de clase siguen siendo los mismos. En general, los profesores no sabemos qué hay afuera; y si eso pasa, pues sigo haciendo lo mismo todo el tiempo. Tiende a pensarse que si tengo un trabajo que funciona, ¿por qué cambiar? Hay que entender que si el mundo se ha transformado, tenemos que cambiar el modo en que enseñamos, el cómo.

¿Qué sugiere a los docentes?

Partir del hecho de que quien más debe trabajar en el aula no es el profesor, sino el estudiante; su función no es acaparar todo el conocimiento y dárselo digerido al alumno. A los niños hay que enseñarles a resolver problemas de manera creativa, distinto a como lo hacen las demás personas. Hay que motivar eso en la clase recurriendo a imágenes, fotos, tecnología, contarles algo y pedirles que lo interpreten…

¿Qué características debería buscar Colombia en aquellos que aspiran a convertir en docentes?

Dos cosas: pasión por los estudiantes y por enseñarles y valorar al ser humano, y pasión por la asignatura, por la disciplina que imparte. Eso debe sentirse para proyectarse. Ese par de cosas no se pueden enseñar. Se tienen o no se tienen.

¿Cómo motivar a miles de profesores que ya hacen parte del sistema educativo pero carecen de esas características?

Colombia ya está revisando currículos, textos y estándares de aprendizaje. Lo primero que hay que hacer es establecer esos estándares. Si tengo que llegar allá, algunos pueden ir corriendo y otros, no; hay que ayudarlos en ese proceso con recursos digitales, guías para profesores, textos, y enseñarles a enseñar con creatividad cada asignatura. Hacerlo tan sencillo que cualquier maestro pueda incorporarlo a su práctica de aula. Cuando el docente ve que va siendo exitoso, se motiva, confía en lo que es capaz de hacer. Hay que asegurarse de que hagan un entrenamiento exitoso.

¿Cree que Colombia va por buen camino?

En la última década, el acceso a la educación ha aumentado de manera significativa en Colombia, y eso es muy bueno; ahora hay que mejorar la calidad de ese acceso, y en eso trabaja el Ministerio de Educación, en materia de textos, currículos, estándares, evaluación continua y entrenamiento docente. Esa es la forma de avanzar. Una vez que se hayan establecido los estándares, es más fácil seguir en este proceso de mejoramiento. Colectivamente, todos los colombianos deben enfocarse en esa meta; sé que hay interés de la sociedad. La idea está. Es un buen punto de partida. Definitivamente, debe ser la prioridad. La economía, la cultura, la unidad de los ciudadanos dependen de la educación.

¿Algún mensaje para los maestros colombianos?

La educación es buscar la verdad, es un concepto socrático. Así es como los profesores debemos vernos. Tengo que sentir que soy un maestro, y no por cuánto me paguen o por las condiciones que me rodeen, sino por quién soy yo. Entender que la docencia está en mi ADN, que mi trabajo no es transmitir conocimientos sino abrir la mente de los niños y los jóvenes y moldear estos destinos que estoy formando en el aula. Si nos concebimos a nosotros mismos como docentes que somos, no necesitamos más arandelas para motivarnos. Eso lo ve la gente, eso lo respeta la gente.

Fuente: http://www.eltiempo.com/estilo-de-vida/educacion/entrevista-con-mike-thiruman-docente-de-singapur/16706184

Imagen: http://www.eltiempo.com/contenido/estilo-de-vida/educacion/IMAGEN/IMAGEN-16706331-2.jpg

Users Today : 150

Users Today : 150 Total Users : 35459745

Total Users : 35459745 Views Today : 271

Views Today : 271 Total views : 3418243

Total views : 3418243