Kenia / 3 de septiembre de 2017 / Autor: EFE / Fuente: Eco Diario

Casi un millón de adolescentes deja de ir al colegio en Kenia cuando tienen el periodo ante la falta de acceso a compresas y a la higiene personal. Su vulnerabilidad crece al no poder comprender qué le pasa a su cuerpo, que se convierte en un tema tabú, y el 60% acaba abandonando la escuela secundaria.

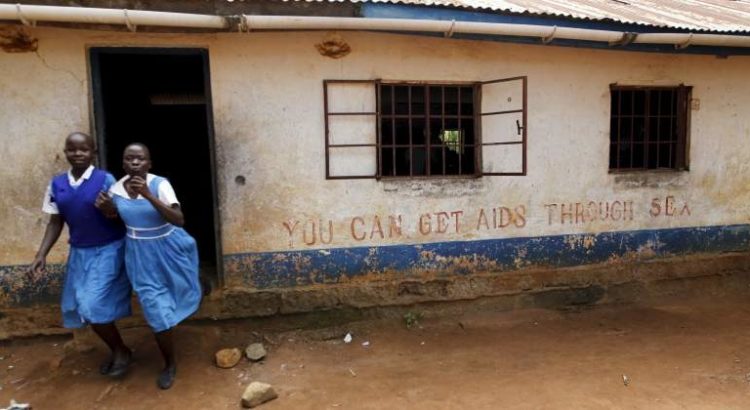

En Kenia, como en otros lugares del mundo, el viaje de las niñas a la adolescencia es un momento difícil. Pero las inseguridades y preocupaciones a las que se enfrentan se intensifican en muchos países africanos ante la casi inexistente educación sobre salud reproductiva.

Para las kenianas, el momento de convertirse en mujeres implica, en la mayoría de los casos, abandonar la escuela y, en consecuencia, sus perspectivas de futuro. Tienen que dejar de ir a clase porque allí no suelen tener acceso a aseos limpios y privados, por lo que no pueden lavarse adecuadamente durante la menstruación.

Además, como las compresas están fuera del alcance del 65 % de las kenianas por su alto coste, muchas tienen que recurrir a otros remedios -telas, hojas o papel- que les pueden provocar infecciones y múltiples inseguridades que les impiden llevar una vida normal.

Esto provoca que casi un millón de niñas se ausenten hasta seis semanas en la escuela, mientras que el 60 % terminan abandonando por esta razón. Algo tan sencillo como una compresa puede transformar a una sociedad entera, permitiendo a las menores continuar con naturalidad su vida, asistiendo a clase junto al resto de sus compañeros y soñar, como ellos, en convertirse en doctoras, ingenieras o profesoras.

La organización Zana ha puesto en marcha diferentes programas -de los que ya se han beneficiado unas 30.000 niñas de entre 11 y 14 años- para mejorar la educación sexual y romper el tabú de la menstruación, que sigue envuelta de estigmas sociales como la vergüenza y la culpa.

«Creemos que la menstruación debe ser celebrada, no ser una vergüenza», reivindican desde Zana, que espera que algún día la gestión de la salud menstrual se reconozca como un derecho para todas las mujeres y niñas en todo el mundo.

Compresas gratuitas

Aunque el objetivo a largo plazo es educar sobre educación sexual y reproductiva -una de cada cuatro niñas desconocen que se pueden quedar embarazadas al tener el periodo- el reparto de compresas gratuitas supone el primer paso para romper el tabú sobre la menstruación.

«Pero las donaciones (de compresas) no son suficiente», explica a Efe la directora general de la citada organización, Megan Mukuria, que insiste en que es necesario cambiar la mentalidad de la sociedad e introducir en el mercado compresas de mayor calidad y más asequibles que permitan una solución duradera.

Por eso, han lanzado una nueva marca de estos productos que ya venden en diferentes asentamientos informales de Nairobi a unos 7 chelines la unidad (menos de un céntimo de euro) que son accesibles para las familias en Kenia, donde el 46 % de la población vive por debajo de la línea de pobreza.

«Estoy muy feliz y agradecida de recibir compresas que me hacen sentir valiosa. Sentí como si me hubieran dado millones de dólares», dice la joven Wambui.

El acceso a la educación para las menores no es solo una cuestión de derechos e igualdad de género, sino también una cuestión económica, porque el crecimiento de los países se contrae si se excluye a las mujeres del mundo laboral.

Según el Banco Mundial, si todas las niñas en Kenia finalizaran la escuela secundaria, habría un aumento del 46 % en el PIB del país a lo largo de su vida. Sin conocimiento sobre su salud reproductiva, las niñas son más vulnerables a enfermedades, embarazos no planificados, matrimonios prematuros forzados o a la mutilación genital femenina.

Las autoridades cada vez son más conscientes de ello, y prueba de ello es que el Gobierno de Kenia prometió -durante la pasada campaña electoral- repartir productos higiénicos gratuitos ente todas las escolares del país.

Fuente de la Noticia:

http://ecodiario.eleconomista.es/africa/noticias/8581726/09/17/El-poder-de-una-compresa-en-Kenia-un-millon-de-adolescentes-deja-el-colegio-por-la-falta-de-acceso.html

Users Today : 21

Users Today : 21 Total Users : 35462871

Total Users : 35462871 Views Today : 58

Views Today : 58 Total views : 3424860

Total views : 3424860