Por Kevin Watkins

Africa’s education crisis seldom makes media headlines or summit agendas and analysis by the Brookings Center for Universal Education (CUE) explains why this needs to change. With one-in-three children still out of school, progress towards universal primary education has stalled. Meanwhile, learning levels among children who are in school are abysmal. Using a newly developed Learning Barometer, CUE estimates that 61 million African children will reach adolescence lacking even the most basic literacy and numeracy skills. Failure to tackle the learning deficit will deprive a whole generation of opportunities to develop their potential and escape poverty. And it will undermine prospect for dynamic growth with shared prosperity.

If you want a glimpse into Africa’s education crisis there is no better vantage point than the town of Bodinga, located in the impoverished Savannah region of Sokoto state in northwestern Nigeria. Drop into one of the local primary schools and you’ll typically find more than 50 students crammed into a class. Just a few will have textbooks. If the teacher is there, and they are often absent, the children will be on the receiving end of a monotone recitation geared towards rote learning.

Not that there is much learning going on. One recent survey found that 80 percent of Sokoto’s Grade 3 pupils cannot read a single word. They have gone through three years of zero value-added schooling. Mind you, the kids in the classrooms are the lucky ones, especially if they are girls. Over half of the state’s primary school-age children are out of school – and Sokoto has some of the world’s biggest gender gaps in education. Just a handful of the kids have any chance of making it through to secondary education.

The ultimate aim of any education system is to equip children with the numeracy, literacy and wider skills that they need to realize their potential – and that their countries need to generate jobs, innovation and economic growth.

Bodinga’s schools are a microcosm of a wider crisis in Africa’s education. After taking some rapid strides towards universal primary education after 2000, progress has stalled. Out-of-school numbers are on the rise – and the gulf in education opportunity separating Africa from the rest of the world is widening. That gulf is not just about enrollment and years in school, it is also about learning. The ultimate aim of any education system is to equip children with the numeracy, literacy and wider skills that they need to realize their potential – and that their countries need to generate jobs, innovation and economic growth. From South Korea to Singapore and China, economic success has been built on the foundations of learning achievement. And far too many of Africa’s children are not learning, even if they are in school.

The Center for Universal Education at Brookings/This is Africa Learning Barometer survey takes a hard look at the available evidence. In what is the first region-wide assessment of the state of learning, the survey estimates that 61 million children of primary school age – one-in-every-two across the region – will reach their adolescent years unable to read, write or perform basic numeracy tasks. Perhaps the most shocking finding, however, is that over half of these children will have spent at least four years in the education system.

Africa’s education crisis does not make media headlines. Children don’t go hungry for want of textbooks, good teachers and a chance to learn. But this is a crisis that carries high costs. It is consigning a whole generation of children and youth to a future of poverty, insecurity and unemployment. It is starving firms of the skills that are the life-blood of enterprise and innovation. And it is undermining prospects for sustained economic growth in the world’s poorest region.

Tackling the crisis in education will require national and international action on two fronts: Governments need to get children into school – and they need to ensure that children get something meaningful from their time in the classroom. Put differently, they need to close the twin deficit in access and learning.

Why has progress on enrollment ground to a halt? Partly because governments are failing to extend opportunities to the region’s most marginalized children. Africa has some of the world’s starkest inequalities in access to education. Children from the richest 20 percent of households in Ghana average six more years in school than those from the poorest households. Being poor, rural and female carries a triple handicap. In northern Nigeria, Hausa girls in this category average less than one year in school, while wealthy urban males get nine years.

Conflict is another barrier to progress. Many of Africa’s out-of-school children are either living in conflict zones such as Somalia and eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, in camps for displaced people in their home country, or – like the tens of thousands of Somali children in Kenya – as refugees. Six years after the country’s peace agreement, South Sudan still has over 1 million children out of school.

The Learning Deficit

Just how much are Africa’s children learning in school? That is a surprisingly difficult question to answer. Few countries in the region participate in international learning assessments – and most governments collect learning data in a fairly haphazard fashion.

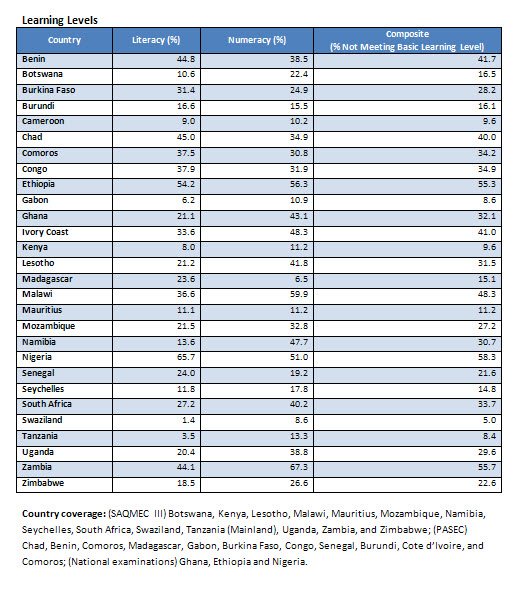

The Learning Barometer provides a window into Africa’s schools. Covering 28 countries, and 78 percent of the region’s primary school-age population, the survey draws on a range of regional and national assessments to identify the minimum learning thresholds for Grades 4 and 5 of primary school. Children below these thresholds are achieving scores that are so low as to call into question the value-added of their schooling. Most will be unable to read or write with any fluency, or to successfully complete basic numeracy tasks. Of course, success in school is about more than test scores.

It is also about building foundational skills in teamwork, supporting emotional development, and stimulating problem-solving skills. But learning achievement is a critical measure of education quality – and the Learning Barometer registers dangerously low levels of achievement.

The headline numbers tell their own story. Over one-third of pupils covered in the survey – 23 million children – fall below the minimum learning threshold. Because this figure is an average, it obscures the depth of the learning deficit in many countries. More than half of students in Grades 4 and 5 in countries such as Ethiopia, Nigeria and Zambia are below the minimum learning bar. In total, there are seven countries in which 40 percent or more of children are in this position. As a middle-income country, South Africa stands out. One-third of children fall below the learning threshold, reflecting the large number of failing schools in areas servicing predominantly low-income black and mixed race children.

Disparities in learning achievement mirror wider inequalities in education. In Mozambique and South Africa, children from the poorest households are seven times more likely than those from the richest households to rank in the lowest 10 percent of students.

Unfortunately, the bad news does not end here. Bear in mind that the Learning Barometer registers the score of children who are in school. Learning achievement levels among children who are out of school are almost certainly far lower – and an estimated 10 million children in Africa drop out each year. Consider the case of Malawi. Almost half of the children sitting in Grade 5 classrooms are unable to perform basic literacy and numeracy tasks. More alarming still is that half of the children who entered primary school have dropped out by this stage.

Adjusting the Learning Barometer to measure the learning achievement levels of children who are out of school, likely to drop out, and in school but not learning produces some distressing results. There are 127 million children of primary school age in Africa. In the absence of an urgent drive to raise standards, half of these children – 61 million in total – will reach adolescence without the basic learning skills that they, and their countries, desperately need to escape the gravitational pull of mass poverty.

What is Going Wrong?

Rising awareness of the scale of Africa’s learning crisis has turned the spotlight on schools, classrooms and teachers – and for good reason. Education systems across the region urgently need reform. But the problems begin long before children enter school in a lethal interaction between poverty, inequality and education disadvantage.

The early childhood years set many of Africa’s children on a course for failure in education. There is compelling international evidence that preschool malnutrition has profoundly damaging – and largely irreversible – consequences for the language, memory and motor skills that make effective learning possible and last throughout youth and adulthood. This year, 40 percent of Africa’s children will reach primary school-age having had their education opportunities blighted by hunger. Some two-thirds of the region’s preschool children suffer from anemia – another source of reduced learning achievement.

Parental illiteracy is another preschool barrier to learning. The vast majority of the 48 million children entering Africa’s schools over the past decade come from illiterate home environments. Lacking the early reading, language and numeracy skills that can provide a platform for learning, they struggle to make the transition to school – and their parents struggle to provide support with homework.

Gender roles can mean that young girls are removed from school to collect water or care for their siblings. Meanwhile, countries such as Niger, Chad and Mali have some of the world’s highest levels of child marriage – many girls become brides before they have finished primary school.

School systems in Africa are inevitably affected by the social and economic environments in which they operate. Household poverty forces many children out of school and into employment. Gender roles can mean that young girls are removed from school to collect water or care for their siblings. Meanwhile, countries such as Niger, Chad and Mali have some of the world’s highest levels of child marriage – many girls become brides before they have finished primary school.

None of this is to discount the weaknesses of the school system. Teaching is at the heart of the learning crisis. If you want to know why so many kids learn so little, reflect for a moment on what their teachers know. Studies in countries such as Lesotho, Mozambique and Uganda have found that fewer than half of teachers could score in the top band on a test designed for 12-year-olds. Meanwhile, many countries have epidemic levels of teacher absenteeism.

It is all too easy to blame Africa’s teachers for the crisis in education – but this misses the point. The region’s teachers are products of the systems in which they operate. Many have not received a decent quality education. They frequently lack detailed information about what their students are expected to learn and how their pupils are performing. Trained to deliver outmoded rote learning classes, they seldom receive the support and advice they need from more experienced teachers and education administrators on how to improve teaching. And they are often working for poverty-level wages in extremely harsh conditions.

Education policies compound the problem. As children from nonliterate homes enter school systems they urgently need help to master the basic literacy and numeracy skills that they will need to progress through the system. Unfortunately, classroom overcrowding is at its worst in the early grades – and the most qualified teachers are typically deployed at higher grades.

Public spending often reinforces disadvantage, with the most prosperous regions and best performing schools cornering the lion’s share of the budget. In Kenya, the arid and semi-arid northern counties are home to 9 percent of the country’s children but 21 percent of out-of-school children. Yet these counties receive half as much public spending on a per child basis as wealthier commercial farming counties.

Looking Ahead – Daunting Challenges, New Opportunities

The combined effects of restricted access to education and low learning achievement should be sounding alarm bells across Africa. Economic growth over the past decade has been built in large measure on a boom in exports of unprocessed commodities. Sustaining that growth will require entry into higher value-added areas of production and international trade – and quality education is the entry ticket. Stated bluntly, Africa cannot build economic success on failing education systems. And it will not generate the 45 million additional jobs needed for young people joining the labor force over the next decade if those systems are not fixed.

Daunting as the scale of the crisis in education may be, many of the solutions are within reach. Africa’s governments have to take the lead. Far more has to be done to reach the region’s most marginalized children. Providing parents with cash transfers and financial incentives to keep children – especially girls – in school can help to mitigate the effects of poverty. So can early childhood programs and targeted support to marginalized regions.

Africa also needs an education paradigm shift. Education planners have to look beyond counting the number of children sitting in classrooms and start to focus on learning. Teacher recruitment, training and support systems need to be overhauled to deliver effective classroom instruction. The allocation of financial resources and teachers to schools should be geared towards the improvement of standards and equalization of learning outcomes. And no country in Africa, however poor, can neglect the critical task of building effective national learning assessment systems.

Aid donors and the wider international community also have a role to play. Having promised much, they have for the most part delivered little – especially to countries affected by conflict. Development assistance levels for education in Africa have stagnated in recent years. The $1.8 billion provided in 2010 was less than one-quarter of what is required to close the region’s aid financing gap.

Unlike the health sector, where vaccinations and the global funds for AIDS have mobilized finance and unleashed a wave of innovative public-private partnerships, the education sector continues to attract limited interest. This could change with a decision by the U.N. secretary-general to launch a five-year initiative, Education First, aimed at forging a broad coalition for change across donors, governments, the business community and civil society.

There is much to celebrate in Africa’s social and economic progress over the past decade. But if the region is to build on the foundations that have been put in place, it has to stop the hemorrhage of skills, talent and human potential caused by the crisis in education. Africa’s children have a right to an education that offers them a better future – and they have a right to expect their leaders and the international community to get behind them.

Users Today : 190

Users Today : 190 Total Users : 35459785

Total Users : 35459785 Views Today : 350

Views Today : 350 Total views : 3418322

Total views : 3418322