Por: Atawallpa Oviedo Freire

A pesar del infame asesinato de 50 seres humanos en Orlando (EEUU), no se han aplacado los cuestionamientos y mofas por parte de los “fieles siervos” de dios, del amor, de la justicia, y de la vida; más por el contrario, han alabado, bendecido y promovido más actos como éste: “Roger Jiménez, pastor de origen venezolano y líder de la iglesia Verity Baptist Church en Sacramento, California, ha acarreado sobre sí una tormenta de críticas por un controversial sermón en el que elogió la masacre de 49 personas en un club gay de Orlando, EE UU, por contribuir a la eliminación de «sodomitas». Aseguró que no pretende incitar a la violencia contra la comunidad LBGT pero dijo que cree que Dios «ha puesto una sentencia de muerte» sobre ellos. [1]

A su vez, en Bolivia, las iglesias cristianas amenazan con marchas y acciones contra la nueva “Ley de Identidad de Género” aprobada recientemente. Y así, por todo el mundo. Me identifico con aquellas visiones que consideran que la religión es todo lo contrario a la espiritualidad, o es la forma en la que la religión utilizando un lenguaje espiritual tiene como propósito desviar al caminante de lo sagrado. Mientras la religión expulsó a dios a un cielo idílico, la espiritualidad vive a dios en todas las formas de la existencia. Si la religión vive para un paraíso en el más allá y un infierno en el más acá, la espiritualidad vive en el presente del aquí y ahora, entendiendo que el paraíso es un estado de consciencia que siempre está con nosotros y en la que jamás habría un dios que podría echarlos fuera, sino, uno mismo. De ahí, que las religiones no viven en este paraíso terrenal sino en un “infierno en la tierra”.

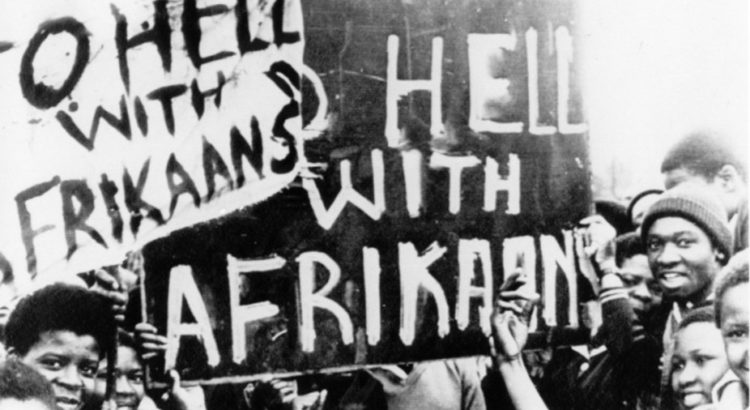

Los que cuestionan a los LGTB, como asimismo otras formas de vida y creencias, envueltos en una prepotencia y arrogancia sempiterna, utilizan a su religión para pretender convertir a sus dogmas en una verdad universal. Una actitud segregacionista y utilitaria del concepto de dios, cuando existen múltiples definiciones y formas de percibir a la divinidad, por lo que no pueden apropiarse de lo sagrado ni hacerse los dueños de las leyes de la vida natural a partir de sus afirmaciones ortodoxas. Lo que estamos viendo, es que se repite o se continua con el mismo esquema ejercido en su proceso de cristianización, de que su dios es el “único” y “verdadero”, para irónicamente y a nombre de él asesinar a millones de seres humanos en todo el mundo. Por ejemplo, se calcula que las diversas matanzas y guerras llevadas a cabo por los cruzados produjeron 5 millones de muertes a lo largo de tres siglos y medio. Las guerras entre católicos y los protestantes franceses de doctrina calvinista o hugonotes, entre 1562-1598, causaron la muerte de al menos 3 millones de seres humanos. En la época de la “santa inquisición” asesinaron a 40.000 mujeres acusadas de brujas. En total, las guerras santas mataron a unos 30 millones de personas en Europa. Lo cual es la mitad, de los 60 millones de habitantes de Amerindia, asesinados bajo diferentes formas, pero todas ellas bajo el esperpéntico argumento de “extirpación de idolatrías”.

Y así, pudiéramos hacer una larga lista de episodios en distintas partes del mundo, de cómo el cristianismo se ha manchado de sangre y de miseria hasta los actuales días con la cantidad de curas pederastas y pedófilos, pasando por los escándalos financieros del banco del Vaticano. Con estos antecedentes, hablan de moral, ética, amor, ciencia, para cuestionar los derechos humanos de los LGTB, con argumentos llenos de fanatismo y de fundamentalismo, haciéndole actuar y hablar a dios como un ser juzgador, sentenciador, discriminador, calificador. Se creen los representantes autorizados por dios, y en su nombre lanzan sus inquisiciones y cacerías cada vez que se van afectando más sus intereses. Y ese es el problema de fondo, pues cada día hay gente más consciente por lo que tienen menos feligreses, como en Europa que ya no tienen a quién cobrar los diezmos o los sacramentos, o en el caso de los otros países, que ya no pueden mantenerlos sumisos al servicio de los gobiernos conservadores de derecha, como fue la misión histórica de la iglesia y las religiones. Algunos, temen que eso se extienda por el resto del mundo y no puedan seguirse haciendo millonarios, como algunos pastores a través de sus radios y canales de televisión.

Desde las religiones monoteístas se concibe a la homosexualidad como un pecado, pero desde las concepciones espirituales habidas en todos los rincones del planeta, no existe una concepción pecaminosa sino de comprensión y de respeto a cada expresión diversa de vida. Han entendido, que es una situación milenaria existente en todos los pueblos del mundo, como otra forma de la manifestación natural de la vida, pues es algo que también se da entre ciertos tipos de animales no-humanos. Vaya a saber, por qué la gran conciencia se ha recreado así. Otro argumento que han esgrimido es que están defendiendo a la “familia tradicional”, es decir, están protegiendo a la familia patriarcal y machista, en la que el hombre es el que dirige, es el referente, el prototipo, y medida de lo que deben ser los demás miembros de la familia. La mujer debe ser sumisa, domeñada y obediente al hombre, y los hijos deben agachar la cabeza a lo que ordena y determina el padre. Como era hasta hace unos pocos años atrás y eso lo quieren mantener o evitar que se disperse más, pues, poco a poco las mujeres e hijos se van emancipando de esa tutela esclavista impuesta.

Incluso, algunos extremistas cristianos alaban el burka que deja libre solo los ojos, como lo hacen con sus mujeres sus primos musulmanes nietos del patriarca Abraham. Esta actitud misógina de sometimiento, es típico de sociedades monoteístas, verticalistas, machistas, fragmentarias. Por ello, estos grupos critican al feminismo (aunque hay un tipo, que solo es el otro lado del machismo); como asimismo, al indigenismo, al etnicismo, al anticapacitismo, al antiespecismo, y todos aquellos paradigmas que cuestionan el religiocentrismo, el paternalismo, el asistencialismo, y todas las formas que apuntalan el sistema de dominación colonial, civilizatorio, monárquico, eurocéntrico. De ahí, que su dios es varón y no admiten el sacerdocio de las mujeres. Empezaron matando a las milenarias diosas-madres y a las sacerdotisas indo-europeas, y luego se han dedicado a asesinar a toda expresión y principio femenino en todas las culturas del mundo. En su recorrido histórico no solo han despreciado a las mujeres, las etnias, la sensibilidad, la sensitividad, y todo lo que representa lo femenino de la vida, sino que también desprecian a la naturaleza (“la manzana prohibida”), por ello su vida ha estado dedicada a hacer cumplir lo que manda el génesis: “dominad a la naturaleza…” De ahí, el calentamiento climático que ha puesto en peligro la existencia de la especie humana.

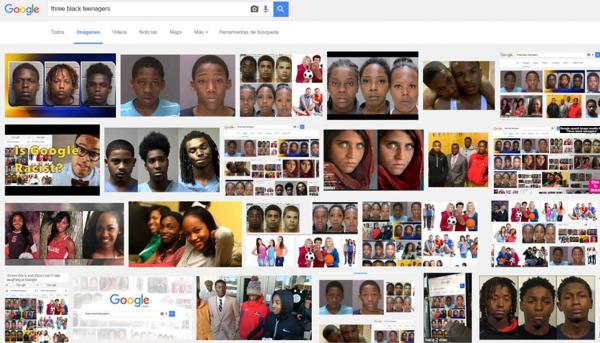

Todo ello, les ha conducido a crear una sociedad sectaria, hegemonista, homogeneizadora y monocromática, la misma, que poco a poco se les está acabando, por lo que han pegado el grito en el cielo con argumentos cosificadores de dios y de la espiritualidad, en el intento de parar esta nueva consciencia que se expande. Les asusta la diferencia, la variedad, la diversidad, y todas aquellas expresiones que enriquecen la vida de múltiples colores como el arcoíris, pues solo quieren vivir en la dicotomía de blancos y negros, de buenos y malos. Por ello, desprecian a todos quienes no sean blancos, de ahí, que hasta Jesús es blanco, rubio, de ojos azules. Lo que quiere decir, que además son racistas. Menosprecian a los dioses y diosas indígenas, y las siguen calificando de idolatrías, de fetichismo, de primitivismo. Siguen repitiendo en sus iglesias y escuelas, que los conquistadores trajeron la civilización y la cultura a esta tierra de infieles y paganos, por eso, alaban y siguen reproduciendo todo lo que provenga de la derecha conservadora occidental. Por lo que también son parte, de los que apoyan a los países industrializados y todos sus conceptos neoliberales, desarrollistas, capitalistas. En respuesta a todo esto, surgió la teología de la liberación, la iglesia de los pobres, los “curas rojos”, etc. Son gente, al interior de las mismas iglesias cristianas que tomaron consciencia del poder de dominación y de manipulación que tienen las religiones monoteístas y sus gobiernos títeres. Ellos, son el claro ejemplo de la crisis de las religiones, que reclaman cambios al interior y exterior de las iglesias, pues saben que estas congregaciones han estado siempre al servicio de los ricos, de los imperios, del status quo, y de todo aquello que represente el poder de control y de sometimiento a quienes se los oponen.

Por ello, y por mucho más, algunos psicólogos de universidades norteamericanas quieren declarar a la religión como una enfermedad. En un reciente artículo de la revista Time se entrega una visión acerca de los daños que podría causar la religiosidad. «La religión puede ser una fuente de consuelo que mejora el bienestar. Sin embargo, algunos tipos de religiosidad podrían ser una señal de problemas más profundos de la salud mental». [2]

Notas:

[1] http://www.el-nacional.com/

[2] https://vistoenlaweb.org/2013/

Fuente: http://www.rebelion.org/noticia.php?id=213677&titular=la-religi%F3n-como-forma-de-dominio-

Fuente de la imagen: http://definicion.de/wp-content/uploads/2008/09/Homofobia2-300×300.jpg

Users Today : 123

Users Today : 123 Total Users : 35459589

Total Users : 35459589 Views Today : 200

Views Today : 200 Total views : 3417958

Total views : 3417958