Turquía/10 de Febrero de 2018/El País

El número de hijos de refugiados que reciben educación se ha multiplicado por cinco en menos de cuatro años, pero aún hay 350.000 menores que no van a clase.

Rukye, de 25 años, proviene de un pueblo al norte de Alepo. Ella su marido y sus entonces tres hijos salieron de Siria hace cuatro años a medida que les llegaban las noticias del avance de Daesh hasta su municipio. Se instalaron en Gaziantep (sur de Turquía) y en este tiempo han añadido un miembro a su familia, la pequeña Hadija. La hija mayor, Lujain, de siete años, no se encuentra en casa porque está en el colegio. «Todavía no sabe qué quiere ser de mayor, por ahora lo importante es que vaya al colegio y aprenda el idioma, porque no sabemos cuántos años nos quedan aquí», sostiene su madre. Su hermana Orjuan, de seis años, empezará a ir a la escuela el curso que viene. No habla turco todavía. «¿Entonces cómo te entiendes con tus amigos de aquí?», le preguntan. «Nos entendemos y ya está», responde ella sonriendo.

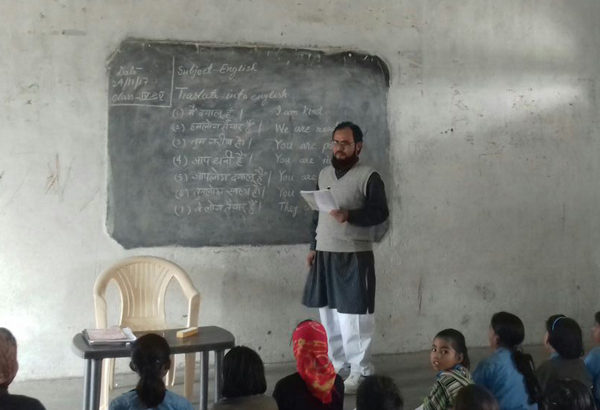

Turquía es el hogar de 3,7 millones de refugiados (en su mayoría sirios), de los que al menos 1,5 millones son menores, según datos facilitados por la Unión Europea y Unicef. 610.000 niños y jóvenes reciben educación tanto en colegios públicos como en centros especiales habilitados para hijos de exiliados por la guerra en Siria. Hace cuatro años solo la recibían 108.000. «Si queremos evitar que toda una generación se pierda, todas las partes tienen que implicarse en la educación. Aún hay 350.000 menores que no van a clase«, explica al otro lado del teléfono el responsable de Unicef en Turquía, Philippe Duamelle. El presupuesto del fondo para este 2018 en la región es de 230 millones de dólares (185 millones de euros).

Las familias reciben dinero extra si envían a sus hijos al colegio. La cantidad es mayor sin son niñas

Desde finales de 2016, la Unión Europea, el Gobierno turco y varios organismos internacionales, como el Porgrama Mundial de Alimentos (perteneciente a la ONU), prestan un servicio de ayuda a los refugiados registrados más vulnerables por el que se les ingresa cierta cantidad de dinero al mes en una tarjeta de débito. Uno de los criterios que hace variar los fondos que se aportan a cada unidad familiar es el número de hijos que tengan. Unicef entró a formar parte de este programa añadiendo un extra de dinero si los servicios sociales constataban que la familia enviaba a los menores a la escuela en lugar de hacerles trabajar para colaborar en la economía de la casa. Entre 40 y 60 liras turcas (entre 8,60 y 12,90 euros) por niña y entre 35 y 55 (entre 7,52 y 11,80 euros) por niño. Unicef actualmente aporta este plus a 190.000 familias. La discriminación positiva ha logrado que el número de varones y féminas que acuden a clase sea prácticamente el mismo.

El plan del Fondo de las Naciones Unidas se complementa con un protocolo especial de protección a la infancia activo en 15 provincias. 900 asistentes sociales y pedagogos recorren las casas de los beneficiarios cada día para detectar las situaciones de riesgo para los niños y prestar asistencia. Hasta ahora, esta unidad de protección ha atendido a 45.000 familias.

Durante los primeros meses de la llegada masiva de refugiados sirios a Turquía no existían ni las mismas estructuras que ahora han establecido las organizaciones internacionales, ni la estrecha colaboración con el Gobierno en vigor actualmente. Esto provocó que durante un largo periodo de tiempo un gran número de menores dejaran de recibir educación y no hayan podido volver a recibir clases. Organismos internacionales y Turquía están negociando nuevas medidas para solucionar esta situación. «Estamos trabajando con el Gobierno en un plan de formación acelerada para volver a incluir a estos 350.000 alumnos en el sistema y que no se pierda su capacidad», señala Duamelle. La iniciativa, según las previsiones, se pondrá en marcha en el primer trimestre de este año.

El 60% de los pequeños acude a colegios públicos y el 40% a centros especiales para refugiados.

La barrera del idioma es un gran obstáculo para los refugiados sirios en Turquía y en muchos casos son los niños, que sí aprenden el idioma, los que actúan como intérpretes de sus familiares. Es el caso de Huda, cuya hija mayor, que también se encuentra en el colegio en el momento en el que hablamos con ella, es prácticamente bilingüe porque llegó al país con apenas cinco años. Huda tiene dos hijos más y asegura que todos ellos irán a la escuela.

El aumento del número de menores que recibe educación se debe en gran medida a la aportación económica del programa de Unicef y también a que el Gobierno turco ha abierto las puertas de sus escuelas a los alumnos hijos de refugiados. «Al principio se plantearon otros protocolos temporales, porque todos pensábamos que esas familias podrían volver a su casa antes. Pero muchas de ellas ya llevan en Turquía ocho años, así que llegó un punto en el que había que establecer un sistema más estable», añade Duamelle. El 60% de los pequeños acude a colegios públicos y el 40% a centros especiales para refugiados en los que se les imparte 16 horas semanales de turco.

EL PRÓXIMO GRAN RETO

La mitad de los menores escolarizados están entre los 6 y los 12 años. Las cifras se reducen a medida que avanza la edad. Nahla, una viuda de 49 años, vive en Gaziantep con seis de sus nueve hijos. Los que tienen entre 9 y 14 años van al colegio, pero el mayor, Marwa, compagina sus clases con el trabajo informal que desempeña en un supermercado como reponedor. Su madre sostiene que la «educación es lo más importante para su futuro», pero también necesita todo el apoyo económico posible para mantener a la familia. A su lado, los dos pequeños, Isra y Nuri, escuchan atentos. Pueden estar por la mañana en casa junto a su madre porque van al colegio en horario vespertino.

El responsable de Unicef en Turquía, Philippe Duamelle, apunta a que también se está trabajando con las autoridades turcas para facilitar el proceso de exámenes de acceso a la universidad para los jóvenes refugiados.

Fuente: https://elpais.com/elpais/2018/01/25/planeta_futuro/1516886063_796193.html

Users Today : 22

Users Today : 22 Total Users : 35462246

Total Users : 35462246 Views Today : 46

Views Today : 46 Total views : 3423257

Total views : 3423257