The recent impeachment hearings in the United States made clear that President Donald Trump abused his office and committed a crime against the Constitution. Not only did he attempt to pressure the Ukrainian government into investigating his presidential political rival Joe Biden and his son Hunter Biden in exchange for military aid, Trump also used the power of his administration to pressure loyal followers, such as Rudy Giuliani (his personal lawyer) to claim that Ukraine, not Russia, had intervened in the 2016 election – a position completely debunked by every US government intelligence agency.

In addition, Trump once again displayed his disregard for the law and the separation of powers by refusing to cooperate with the House impeachment inquiry, claiming that the evidence pointing to his use of power to secure political favors from the Ukrainian government was fake news and amounted to nothing more than a witch hunt. Moreover, he escalated his contempt for the proceedings by conducting a smear campaign against investigators leading the hearings by calling them “human scum.” And he threatened Marie L. Yovanovitch, the former ambassador to Ukraine, who criticized Trump’s policies with Ukraine, and derided media outlets that critically covered the event.

At the same time, Trump made clear his disdain for any viable notion of justice by pardoning three American servicemen accused of war crimes. There is more at stake here than simply a president’s abuse of office for political gain and his authoritarian embrace of unaccountable power and a shameful disregard for the law. Trump has launched a direct attack on the ideological, institutional and ethical foundations central to the functioning of a democracy.

Trump Playbook

Meanwhile, in Brazil, President Jair Bolsonaro has repeatedly attacked Indigenous groups working to protect the environment from illegal loggers and from lawbreaking networks that are driving the destruction of the Amazon. In doing so he has given a green light to groups that are illegally pillaging the rainforest and threatening to kill Indigenous people, small farmers, law enforcement agents and anyone else who tries to stop them. Exhibiting a Trump-like embrace of solipsism, the spectacle of distraction, and a penchant for political absurdity, Bolsonaro has falsely accused actor Leonardo DiCaprio “of bankrolling the deliberate incineration of the Amazon rainforest” and praised Augusto Pinochet’s military coup in Chile in 1973. Unsurprisingly, Bolsonaro has also expressed his support for Brazil’s 1964-1985 military dictatorship on a number of occasions. And when faced with opposition, he draws from the Trump playbook by producing scapegoats.

Resistance to the emboldened authoritarianism of Bolsonaro’s government is growing in Brazil, however, especially with the release from prison of former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. Protests are occurring daily in the streets of Brazil, though not on the scale in which they are taking place in Colombia, Bolivia, Chile and Ecuador, and in spite of accelerating state repression. The massive protests that have occurred in Bolivia, Chile, Colombia and Ecuador have been met with violent police abuse and state repression.

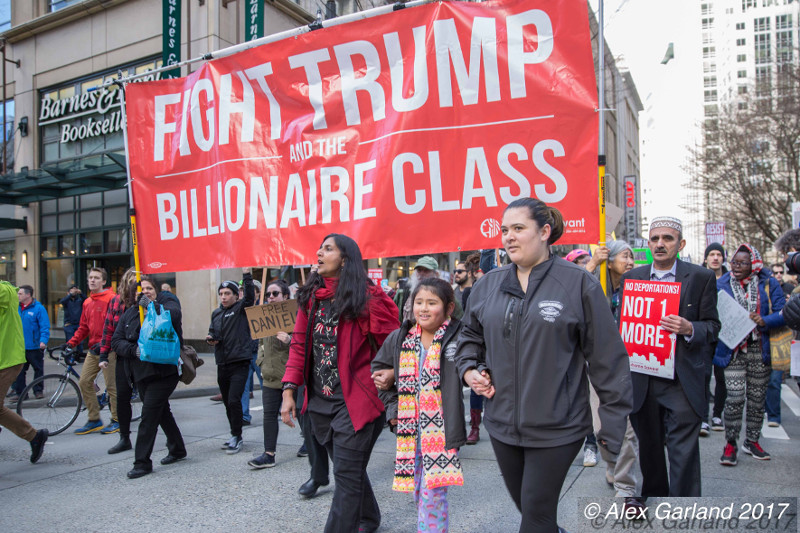

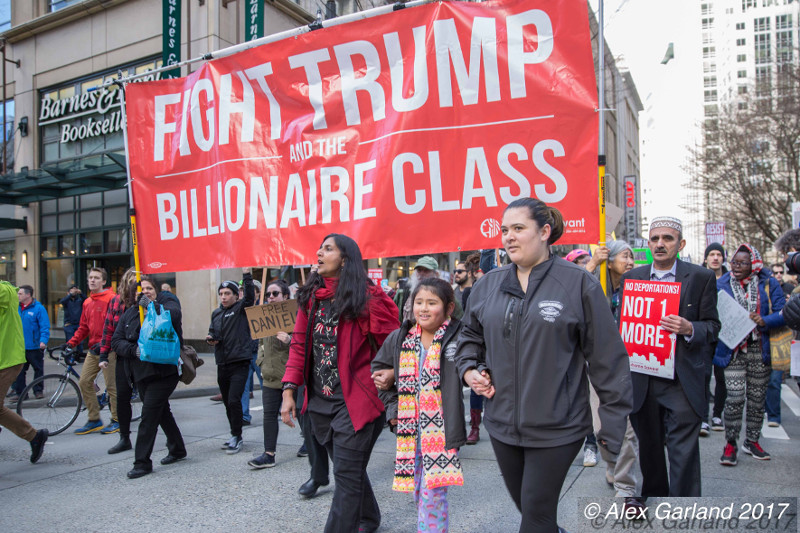

These events may seem unrelated, but in fact they are part of intertwined trends that are transforming the political landscape across the globe. These movements of resistance represent a reaction to the multiple abuses produced by a mix of political authoritarianism and neoliberalism marked by cruel predatory policies, a disdain for human rights, and fascist claims to ultra-nationalism and social cleansing. In Chile, Bolivia, Colombia and other Latin American countries, people are organizing against a neoliberal system that denies meaningful health care, a decent pension system, quality education, public transportation, investment in public goods, and social mobility to the underclass of people deemed as disposable. In countries such as Hong Kong, the United States and Brazil, there are growing movements for democratic rights, solidarity and economic equality. In this instance, resistance movements share the struggle for combining struggles for economic equality, social justice and minority rights.

In other words, two distinct political tremors are shaking the world: the spread of resistance to rising neo-fascism (evident in places like Brazil and the United States) on the one hand, and a new surge in massive forms of collective resistance against neoliberalism (evident in places like Chile and Colombia) on the other.

These movements, which are engaging in massive forms of collective resistance, are aiming to destroy the structures and ideological plague of neoliberal global capitalism, with its relentless attacks on public goods, unions, social provisions and the ecosystem, as well as its relentless drive to privatize everything and turn all social relations into commercial transactions.

Taken together, these two movements are confronting the interrelated and mutually compatible demons of neoliberalism and fascist politics. Moreover, both movements are predicated on the need to engage the role of the symbolic as a political site where politics can be rethought and collective strategies can emerge.

Toward a Politics and Pedagogy of Everyday Life

Pedagogy as a politics of persuasion, identity formation and resistance offers up the opportunity for such movements to speak to a vision that addresses the core values of justice, equality and solidarity while taking on economic inequality, corporate power and racial injustice. Rather than talk in abstractions about freedom, equality and justice, it is crucial for radical political movements to frame their language in relation to the everyday experiences and problems that people face. For instance, it is important for radical social movements to fashion a language that resonates politically and emotionally with peoples’ needs, values and everyday social relations while embracing the core values of equality, freedom, solidarity and justice. Leah Hunt-Hendrix points to the importance of addressing such core values in the US. She writes:

“Millions of Americans – whether they’re people of color, white, immigrants; whether they live in cities, suburbs, small towns or the country; whether they’re Republicans, Democrats, independents, voters or non-voters – living in poverty or struggling to make it from paycheck to paycheck. Millions are unemployed or underemployed, choosing between health care, heat or housing. Many more feel like they’re slipping behind and lack the economic security they once had.”

At the same time, movements in Chile, Colombia and Ecuador are mobilizing against the twin evils of neoliberalism and fascism, and are demonstrating the need to address the cultural forces shaping society. Such forces are viewed as constitutive of the very nature of politics and modes of agency that both repress progressive alternatives and make them possible. Such movements are not only addressing the educative nature of neoliberal politics, but creating the theoretical and pedagogical groundwork for giving people the tools for understanding how everyday troubles connect to wider structures of domination. This pedagogy of resistance is critical of the attack on notions of the democratic imagination, redemptive notions of the social, and the institutions and formative cultures that make such communities, public goods and modes of solidarity possible. A radical pedagogy in this instance functions to break through the fog of manufactured ignorance in order to reveal the workings and effects of oppressive and unequal relations of power. Pedagogy as a tool of resistance opens up a space of translation, critique and resistance.

Atomization Makes Us Vulnerable to Oppressive Regimes

One reason the movements in Chile, Colombia and Ecuador have gained momentum is through their successful resistance to the atomization that isolates individuals and encourages a sense of powerlessness by claiming the existing order cannot be changed. They have at times succeeded in countering this atomization by refusing what Robert Jay Lifton in a different context calls a “malignant normality.” That is, the imposition of “destructive versions of reality” and the insistence “that they are the routine and the norm.”

This is particularly crucial because atomization is one of the conditions that make oppressive regimes possible. In order to dismantle these regimes, we must also find a way to break out of the patterns of atomization that enable them.

Leo Lowenthal writing in Commentary in January 1, 1946, writes about the atomization of human beings under a state of fear that approximates a kind of updated fascist terror, one that echoes strongly with the present historical era. Hannah Arendt went further and argued that, “What prepares men for totalitarian domination in the non-totalitarian world is the fact that loneliness, once a borderline experience usually suffered in certain marginal social conditions like old age, has become an everyday experience of the ever growing masses of our century.” She elaborates her view of loneliness as the precondition for fascist terror when she writes:

“Loneliness, the common ground for terror, the essence of totalitarian government, and for ideology or logicality, the preparation of its executioners and victims, is closely connected with uprootedness and superfluousness which have been the curse of modern masses since the beginning of the industrial revolution and have become acute with the rise of imperialism at the end of the last century and the break-down of political institutions and social traditions in our own time. To be uprooted means to have no place in the world, recognized and guaranteed by others; to be superfluous means not to belong to the world at all.”

What both understand, writing in the aftermath of the ravaging destruction produced by fascism and World War II, is that democracy cannot exist without the educational, political and formative cultures and institutions that make it possible. Moreover, atomized, rootless and uninformed individuals are not only prone to the forces of depoliticization, but also to the false swindle and spirit of populist demagogues, and the discourses of hate and the demonization of others.

We live in an age of death-dealing loneliness, isolation and militarized atomization. If you believe the popular press, loneliness is reaching epidemic proportions in advanced industrial societies. The usual suspect is the Internet, which isolates people in the warm glow of the computer screen while reinforcing their own isolation and sense of loneliness. The notion of friends and likes become disembodied categories in which human beings disappear into the black hole of abstractions and empty signifiers.

Many blame the internet for this development, but the rootlessness and loneliness on display in many internet-facilitated interactions actually predate the internet. In neoliberal societies, even before the invention of the internet, dependence, compassion, mutuality, care for the other and sociality were already undermined by a market-driven ethic in which self-interest becomes the organizing principle of one’s life, and a survival-of-the-fittest mode of competition breeds a culture that promotes an indifference to the plight of others, a disdain for the less fortunate, and a widespread culture of cruelty aimed at those considered poor, “disposable” and excess.

Isolated individuals do not make up a healthy democratic society. A more theoretical language produced by Marx talked about alienation as a separation from the fruits of one’s labour, and while that is certainly more true than ever, the separation and isolation now is more extensive and governs the entirety of social life in a consumer-based society run by the demands of commerce and the financialization of everything. Isolation, privatization and the cold logic of instrumental rationality have created a new kind of social formation and social order in which it becomes difficult to form communal bonds, deep connections, a sense of intimacy and long-term commitments.

Neoliberalism has created a society where pain and suffering are viewed as entertainment, warfare a permanent state of existence and militarism as the most powerful force shaping masculinity. Politics has taken an exit from ethics, and thus the issue of social costs is divorced from any form of intervention in the world. This is the ideological metrics of political zombies and the currency of neoliberal fascism. The key word here is atomization, and it is a curse imposed by both neoliberal and authoritarian societies while also posing a dire threat to any viable form of democracy.

Toward a Politics of Investment

As we are witnessing in Chile, Ecuador, Hong Kong and Brazil, the heart of any type of politics wishing to challenge this flight into authoritarianism is not merely the recognition of economic structures of domination, but something more profound – which points to the construction of particular identities, values, social relations, or more broadly, agency itself. Central to such a recognition is the fact that politics cannot exist without people investing something of themselves in the discourses, images and representations that come at them daily.

Rather than suffering alone, lured into the frenzy of hateful emotion, individuals need to be able to identify – see themselves and their daily lives– within progressive critiques of existing forms of domination and how they might address such issues not individually, but collectively. This is a particularly difficult challenge today because the scourge of atomization is reinforced daily not only by a coordinated neoliberal assault against any viable notion of the social, but also by an authoritarian and finance-based culture that couples a rigid notion of privatization with a flight from any sense of social and moral responsibility. Moreover, under the dynamics of a fascist political machine, power is concentrated in the hands of a small financial elite that promote divisiveness and hatred through appeals to white nationalism, a deep contempt for liberalism, a propensity for violence and a suppression of dissent.

The atomization of individuals in fascist and neoliberal societies finds its counterpart in the often fatal political fragmentation that is often seen on the left with its proliferation of different groups articulating and addressing often single-issue forms of oppression, whether they are rooted in some version of identity politics or specific instances of domination such as issues associated with climate change. This is not to suggest such struggles are not important politically. On the contrary, what is crucial and equally important is the strategic imperative to unite them around a politics of solidarity that can get them to work together through narratives that, as Nancy Fraser and Houssam Hamade argue, unite struggles for emancipation and social equality.

Feminist scholar Zillah Eisenstein captures insightfully and with great lyrical power the necessity for coalition building as part of a politics of solidarity. She writes:

“Coalitions are part of building solidarity with and between the differences. They are demanded by the complexity of our presences. We must move with and beyond the categories that push us apart like center and margin; we must move beyond binaries that separate and divide, and instead find a way toward connectedness that denies unity, or oneness, and instead images solidarity and its tensions. This is a moment for cross-movement and intersecting actions that will create new alliances that we might not know or imagine yet. This means supporting autonomous actions that become cross movement through the intersections that exist within each.”

A politics of solidarity could incorporate calls for health care, higher wages, decent pensions, access to quality education, a clean environment, and social goods that improve the dignity and quality of life for everyone. What is needed in this case is a politics that awakens new modes of identification, desire and self-reflection. Stuart Hall was right when he argued in the journal Cultural Studies that, “There’s no politics without identification. People have to invest something of themselves, something that they recognize is of them or speaks to their condition, and without that moment of recognition… Politics also has a drift, so politics will go on, but you won’t have a political movement without that moment of identification.”

The cultural apparatuses controlled by the 1 percent are the most powerful educational forces in many authoritarian societies, and they have been transformed into disimagination machines – apparatuses of misrecognition, ignorance and cruelty. Collective agency is now atomized, devoid of any viable embrace of the social. Too many people on the left and progressives have defaulted on this enormous responsibility for recognizing the educative nature for politics and for challenging this form of domination, working to change consciousness, and make education central to politics itself. Democracies are only as strong as the people who inhabit society. Put differently, the relationship between culture and politics becomes clear in the understanding that democracy’s survival depends on a set of habits, dispositions and sensibilities of a formative culture that sustains them.

Authoritarians Use Miseducation to Maintain Power

Trump plays to and manipulates the media because he understands how politics and theater merge in an environment in which the spectacle becomes the only politics left. He does not want to change consciousness, but to freeze it within a flood of shocks, sensations and simplisms that demand no thinking while erasing memory, thoughtfulness and critical dialogue.

For authoritarians like Trump and Bolsonaro, miseducation is the key to maintaining power. In addition, they use the media, schools and other cultural institutions to kill the social imagination, collapse the distinction between the truth and falsehoods, and abolish the line between civic literacy and lies. Education in the broadest sense has become a powerful weapon not merely of propaganda, but a tool of power in the shaping of desires, identities and one’s view of the future. The central political issue here is not about the emergence of an existing reign of civic illiteracy, but about the crisis of agency, the forces that produce it, and the failure of progressives and the left to take such a crisis seriously by working hard to address the symbolic and pedagogical dimensions of struggle – all of which is necessary in order to get people to be able to translate private troubles into wider social issues. The latter may be the biggest political and educational challenge facing those who believe that the current political challenge is not between simply Trump and progressives who rail against the financial elite and big corporations, but over those who believe in democracy and those who do not.

The threat to the planet and humankind is so urgent that there is no space in between from which to refuse to challenge these predatory political movements. The machinery of social and political death unleashed by the avatars of greed, disposability and exploitation parades its horrors like a badge of honor, all the while escaping into the global networks of finance and social irresponsibility, while preaching a feral nativism and developing a politics of entrenched walls and borders. Against these new political formations – as is evident in resistance movements in Puerto Rico, Ecuador, Iraq, Lebanon and Hong Kong – movements for resistance have developed that are global, mobilized by millions, and call not to win justice through often rigged and corrupt elections, but to shut down the militarized institutions, cultures and ideologies of racism, exploitation and death through direct action. When thousands take to the streets, the punishing state loses the only weapon it has left: sheer repression. If these authoritarian states imprisoned and killed millions, such actions would attract even more resistance. Susan Buck-Morss, the author of Revolution Today, is right in writing:

“In order to challenge the illegality of law itself, the force that is needed has nothing to do with firearms. It is the overwhelming, globally democratic force of numbers across every line of difference. The way to prevent an ‘end to democracy’ is to make democracy the means.”

Any viable strategy for change needs a politics that informs the masses and immobilizes the ruling elite. Also needed is a politics that shuts down the flow of capital, the production of misery and the institutions that make it possible.

This suggests a politics that must unite workers, educators and others across the boundaries of race, class and a range of other oppositional movements. The biggest challenge to create such a unified movement speaks not only to a crisis of politics, but agency itself. Such a politics is only possible if it is accompanied by rigorous forms of self-reflection and self-determination as well as a rejection (as Theodor Adorno once put it) of the educational ideal of hardness and toxic masculinity that informs and shapes current right-wing populist movements. Paul Valery’s insistence that “inhumanity has a great future” can only survive if people accept the alleged universal presupposition that power is only about domination and that nothing can change.

As Byung-Chul Han argues in What is Power?, power exceeds the domination of the will, and its affirmation and use are never far from both a critique of oppressive power relations and a full-fledged resistance to them. Rather than only acting so as to repress freedom, power also constitutes itself through the production of freedom. If there is to be a successful challenge to the rise of neoliberal fascism across the globe, the root causes of the current political and economic threats to humankind must be uncovered by recognizing the “societal play of forces that operate beneath the surface of political forms.” In part, this means being historically aware of what forces are at work in a number of countries that signal the rise of new forms of authoritarianism and modes of fascist politics. While no historical moment provides the perfect mirror to the current crisis, our current situation offers up warnings about how the horrors of the past can crystallize into new forms.

Without Hope, There Is No Possibility For Resistance

Central to such a task is recognizing that the globe faces a crisis not only of politics, but also of memory, history, agency and hope. Without hope, there is no possibility for resistance, dissent and struggle. Agency is the condition of struggle, and hope is the condition of agency. Hope expands the space of the possible and becomes a way of recognizing and naming the incomplete nature of the present. It is worth noting that the US is suffering from a crisis of agency brought on in part by a crisis of civic literacy, education and the heavy hand of relegating millions to an ethic of sheer survival. As civic institutions collapse under the ideological and economic weight of global neoliberalism, a unique blend of fascist politics – with its hyper nationalism, call for racial purity, religious extremism and market fundamentalism – operates in what appears to be an ideological ecosystem of ignorance, power and alleged common sense, not to mention the allure of hatred, bigotry and racism.

One consequence is that the inability to relate to and identify with the suffering of others has reached crisis proportions in the current historical moment. This is a politics that celebrates brutality, aggression and sadism, and can be seen in the exercise of state terrorism in Brazil against ecological activists trying to save the Amazon rainforest, and in the United States in the separation and incarceration of undocumented immigrants and their children. In this plague of human cruelty and misery, what must be addressed is an understanding of the forces at work in the updated fusion of fascism and neoliberalism that now dominates a number of countries. At the very least, this is a politics in which political zombies masquerade as patriots, all the while promoting forms of racial and economic fundamentalism and social cleansing.

In the current historical moment, fascism in its neoliberal forms has moved to the center of power in a number of countries, such as Brazil and the United States, and it represents a unique political formation that is haunting the globe. If it is to be challenged, we must rethink how dominant politics resonates with the simplified discourses of populism and easily accommodates the call for strongmen to take over the reins of governance. To do so we must critically analyze the educational conditions that allow individuals to surrender their sense of agency, modes of identification and dreams to the ideological and political forces of neoliberal fascism.

At the heart of this issue is the question of how education can enable forms of self-formation that enable people to resist fascist and neoliberal mentalities, which are inevitably present within cacophonous democratic political modes of governance. To resist these mentalities, we must expose the ideological and economic workings of power and collectively embrace the need to engage in direct action in order to shut down the machineries of death. People in Chile, Puerto Rico, Hong Kong, Ecuador, and Iraq, among other countries, are rising up against the corruption and brutal austerity measures produced by neoliberalism and in doing so they are producing a fierce critique of capitalism and constructing a new understanding of politics and mass resistance. These protests are occurring at a crucial time when the forces of militarism, state violence and disposability are on the march. Under such circumstance, it is crucial to remember – as Marx once stated – that history is open and is made by human beings. It is in precisely that warning and hope that democracy will either perish or thrive. •

This article first published on the TruthDig.com website.

Users Today : 93

Users Today : 93 Total Users : 35410243

Total Users : 35410243 Views Today : 112

Views Today : 112 Total views : 3341607

Total views : 3341607