Por: Dayron Roque

A propósito del artículo “Educación y autoritarismo”, de Miguel Alejandro Hayes.

No parece tener que preocuparse la derecha por hacer labor de convencimiento ideológico, cuando cierto sector de la izquierda se dedica casi con mayor ahínco a embelesar a la gente mientras dice que la combate. Ese parece ser el caso del artículo Educación y autoritarismo, publicado de manera reciente en algunos medios digitales. El asunto se enmarca en la inexistencia de un debate público acerca de la filosofía de la educación en nuestro país —en tanto es enmascarado en «debates» sobre algunas de sus manifestaciones más prácticas y puntuales—.

Lo que parece ser el tema central del texto en cuestión es cómo la educación tiene determinada influencia en la política —¿o la política en la educación?—. El carácter político de la educación es incuestionable: la escuela es una zona política compleja y contradictoria; esto es que, es un espacio donde viven mecanismos de reproducción de la dominación y, a la vez, un campo donde se construyen estrategias y alternativas de oposición, contestación y resistencia. Toda escuela tiene su «contraescuela», y ello es un asunto que interesa a la política.

Como cabe suponer, en el análisis de tal realidad, existe un abanico muy amplio de posiciones desde la extrema derecha hasta la extrema izquierda. Cada una, incluso, ha tenido la oportunidad de «ensayar» su tipo de escuela en determinados momentos y condiciones concretas. Mientras unos ven a la escuela bajo un manto de santidad y neutralidad, otros la observan «vigilantes» como «cómplice del adoctrinamiento» estatal y/o privado.

No creo que la razón esté en el «medio» de ambos posicionamientos: sería una solución salomónica muy fácil, pero errada; sobre todo si se toma en cuenta que en un extremo y otro del panorama político se repiten iniciativas, concepciones y prácticas educativas.

La derecha —que incluye, de paso, a la disfrazada de «centroizquierda»— ha logrado popularizar determinados discursos sobre la escuela que han sido «comprados» con mucho entusiasmo por la izquierda: entre ellos, la escuela como un «aparato ideológico del Estado», o que la autoridad deviene, «naturalmente» en autoritarismo en la escuela. Lo grave no es que haya personas que tengan el criterio —incluso demostrado con hechos de infelices ejemplos, que pretenden hacer pasar por la «regla»— de que la escuela solo sirve para «vigilar y castigar»; lo grave es que esas personas se hagan llamar de izquierda —y «marxista»— y que, además, que presenten su discurso como «progresista».

No es reciente la idea de ciertos sectores de la izquierda ejercer la crítica de la educación escolarizada, en el entendido de que reproduce estructuras de dominación, inherentes a toda sociedad organizada, incluyendo —dicho sea, con humildad— las que se han llamado «socialistas», a lo largo de la historia universal —la tradición anarquista, con tesis de indudable valor, ha estado en el «borde delantero» de tales esfuerzos—. El asunto en sí no es menor, pues se ubica en el centro de una de aquellas famosas tesis marxianas —sobre el tal Feuerbach— de que «el educador necesita ser educado», quizás dejada inconclusa al faltarle —por lo menos— una pregunta: ¿y cómo?

El artículo de referencia da pie para profundizar en varios aspectos de la vida en las escuelas y de la necesidad de profundizar en la misma, como parte de la necesidad de reflexionar sobre toda la vida en nuestro país. Con independencia de que trataré de profundizar en los nudos más conflictivos del mismo, en principio me permito señalar algunas cuestiones puntuales que son, cuando menos, inexactitudes de «forma»:

- dice el autor que la «educación en Cuba no pudo zafarse de los tipos decimonónicos que llegaban de la metrópoli española». Sobre el particular cabe apuntar que la educación que persiste en Cuba tiene sin dudas, origen hispano; pero agotarlo ahí es, cuando menos, insuficiente. En realidad, le debe, y no poco, a la influencia estadounidense — a partir de finales del siglo xix y durante la primera mitad y poco más del xx; quienes fueron los primeros en convertir cuarteles en escuelas en 1899 y además de traernos tazas sanitarias para las escuelas, nos legaron una organización del sistema escolar más moderna y que, en esencia subsiste hasta el día de hoy — y; con posterioridad, a la influencia proveniente del extinto campo socialista — en especial la antigua URSS y la desaparecida RDA, quienes nos legaron una muy desarrollada psicología y didáctica de la matemática, por poner un ejemplo — . En la base de todo ello hay una versión muy criolla de lo que es la educación y la escuela que se vino fermentando desde inicios del siglo xix, se consolidó en la primera mitad del xx y tuvo su esplendor en la época revolucionaria — lo que permitió hacer una campaña de alfabetización en 1961, con un programa y manual hechos, en su totalidad, por educadores cubanos, que sin sonrojo ninguno ubicaba como las primeras letras a aprender «A», «E» y la «O», para formar una frase bien retumbante como «Con OEA, o sin OEA ganaremos la pelea», experiencia que estaría en el germen de lo que años después sería el movimiento de la educación popular latinoamericana, según Paulo Freire; de los logros de la educación revolucionaria un organismo tan poco sospechoso de simpatizar con la Revolución Cubana, como el Banco Mundial no tuvo más remedio que reconocerlo en los años ¡ochenta! — . El carácter repetitivo y memorístico de la escuela cubana no es responsabilidad exclusiva de ninguna de las raíces educativas de nuestro sistema: esos males se pueden apreciar en cualquiera de ellos, desde el siglo xviii hasta la actualidad, en Cuba se «acriollaron».

- «la repetición es la madre de la enseñanza», y es cierto; lo que no es «madre absoluta» o «madre despótica». No hay — a riesgo de ser totalizador — ningún aprendizaje que no se produzca sobre la base de determinadas dosis de repetición que varían en dependencia del objeto de estudio y los sujetos cognoscentes. Ahora bien, ni toda enseñanza es, solo, repetición; ni toda repetición, determina, per se, aprendizaje. Lo perverso no es que haya repetición en la enseñanza, lo perverso es que la enseñanza se reduzca a la simple repetición.

- lo que se entiende por «escuela tradicional» es un complejo cada muy amplio de experiencias y prácticas educativas, que no se reducen — ni con mucho — a las catequesis, ni al aprendizaje de los productos básicos en la educación primaria. Hay, al día de hoy, escuela «contemporánea» donde se memoriza, y escuela tradicional donde la memorización ocupa un papel menor. En cualquier caso, no son las prácticas memorísticas las que determinan el carácter tradicional de la escuela. La falsa dicotomía entre memorizar y aprender, o entre memorizar y aprehender; soslaya el hecho de que la memoria es un nivel del conocimiento, ni mejor ni peor que los otros niveles del conocimiento — la sensopercepción, la imaginación, y el pensamiento mismo — ; sino que solo eso: un nivel por el que se transita en el conocimiento. Sobre la «escuela tradicional» comentaré en detalles más adelante.

- el autoritarismo no se reproduce porque el profesorado intente «trasmitir» un «paquete de información». Hay «paquetes de información» que son imprescindibles «trasmitir» a otras personas; a lo que hay que poner atención, es cómo se determina el contenido del «paquete» — porque lo que es innegable es que en no pocos casos la enseñanza se ha llenado de respuestas a preguntas que los estudiantes no se han hecho; lo cual no sería grave si fueran respuestas a preguntas que nunca se harán a no ser por una buena educación, por ejemplo, «¿gira el sol alrededor de la Tierra?» o «¿es natural que existan personas ricas y pobres?»; sino que lo es porque le enseñan cosas de la que jamás tendrán conexión o explicación con su vida, o que, en el peor de las casos los entretiene en cuestiones colaterales — y cómo se comparte. Autoridad y autoritarismo no es lo mismo; ni dirección del aprendizaje es autoritarismo.

- un descubrimiento notable del marxismo — y más que del marxismo, de las prácticas revolucionarias en los últimos doscientos cincuenta años, de lo que lo mejor de la tradición marxista ha bebido — , en materia de liberación, es que nadie libera a nadie, las personas se liberan en comunión: el educador autoritario se libera por la acción mancomunada de los educandos, que al liberarse, lo liberan.

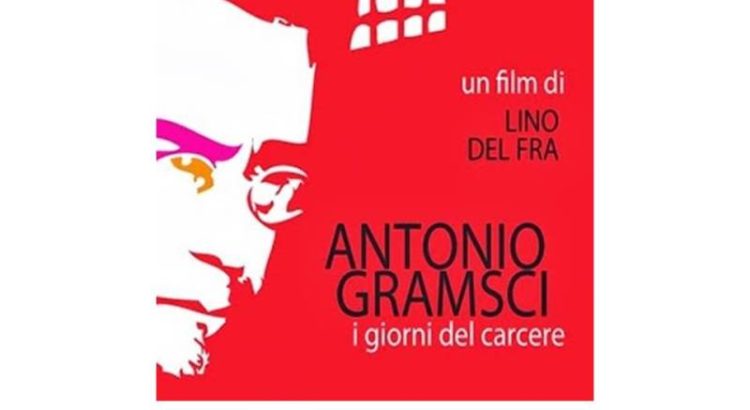

- el sentido común — en la concepción gramsciana, que lo comprende como la «filosofía de los no filósofos», y que suele ser el peor de los sentidos, por oposición al «buen sentido» — es cierto que se forma en la escuela, pero no solo ahí — lo cual es señalado por el propio Gramsci y luego por Althusser — ; de hecho, en los tiempos que vivimos, ya mucho menos de lo que se formaba hace un siglo o hace incluso cincuenta años — y el asunto de cómo la escuela pública ha sido puesta bajo ataque, ha sido deslegitimada y su influencia disminuida frente a otros «productores de sentido común», excede los propósitos de estas líneas y es un tema a investigar con profundidad — . Y ello ha sucedido, en un entorno en el que, de manera paradójica, ha crecido la población escolarizada en el mundo — el «ejército de reserva» mundial no está formado, en su mayoría, por analfabetos sino por graduados universitarios de carreras que no logran encontrar trabajo — . Sin embargo, ya, cada vez menos, se cumple la idea aquella — de inspiración althusseriana — de que ninguna institución «dispone durante tantos años de la audiencia obligatoria, cinco a seis días a la semana, a razón de ocho horas», y no solo en términos cuantitativos de horas en un aula docente, sino por la influencia real que ejerce.

Como algunos de los puntos anteriores merecen una explicación más detallada que un párrafo, voy a exceder el límite del análisis y desarrollar algunas ideas enunciadas como titulares.

Sobre la «escuela tradicional»

En época de indudables avances tecnológicos que llegan a las escuelas, y, sobre todo, de proliferación de teorías de toda laya sobre la educación puede ser difícil discernir entre lo que es escuela «tradicional», y lo que no lo es.

Aunque existe educación desde que el ser humano se alzó sobre sus pies y tuvo necesidad de trasmitir a las nuevas generaciones determinados saberes ordenados, de forma sistemática — lo que explica la idea de la educación como «categoría eterna» — ; la escuela, en su concepción moderna y occidental — la que nos llega a nosotros en Cuba, pero que, dicho sea con pena, deja por fuera la experiencia educativa de las culturas organizadas orientales, en especial, la china que, sin embargo, legó a la educación occidental un instrumento «imprescindible»: los exámenes — ; es una construcción nacida entre el fin de la Edad Media y el inicio de la Modernidad capitalista — su origen aparece en las órdenes religiosas que se dedicaron al asunto de la educación: jesuitas, claretianos, salesianos — . Cuando muchos hacen referencia a la «educación tradicional» — o, con más exactitud a la «escuela tradicional» — , en realidad señalan a esa institución que nació como parte del movimiento de la Ilustración europea, en sus diversas variantes — hace rato quedó claro que no es lo mismo el modelo educativo inglés, la escuela prusiana, o la escuela francesa, por pensar en una comparación rápida — .

A la escuela tradicional se le endilgan, por igual, muchos aciertos y perversiones; en dependencia de quien lo apunte. También, cabe decir, hay diversas gradaciones en cuanto a la «tradición» de que se trate y el papel asignado al profesorado, el estudiantado, el contenido de la educación, y el papel del Estado y la sociedad, entre otros. No obstante, hay un número de características que, de manera común, la tipifican, entre otras:

- la escuela es el lugar por excelencia en el que las «viejas» generaciones educan a las «nuevas» generaciones y le trasmiten su corpus de valores morales, habilidades sociales y conocimientos esenciales.

- la educación es función del Estado, porque la sociedad «educa» a través del Estado; pero es, a la vez, ¡neutral! [Hay que reconocer, que, en rigor, desde la educación tradicional, o, con más exactitud, desde la pedagogía que la sustenta, es donde menos se reconoce el papel del Estado como un instrumento de represión y legitimación ideológica, con probabilidad, como veremos más adelante, porque no se propone «desmontar» — en términos analíticos, no de acción política — tal Estado, ni distingue entre un Estado tiránico, uno monárquico, y uno demorrepublicano.]

- la confianza y el respeto son la base de la educación, aunque para ello haya que apelar al terror y el autoritarismo. Aquí lo curioso es que, en teoría, no se trata de una escuela autoritaria, el autoritarismo sería una «desviación», un «exceso», en determinadas condiciones. En cualquier caso, se trata de un «delicioso despotismo» que sería agradecido por el estudiantado, como parte de su educación para la vida: una versión del «no muerdas la mano que te da de comer».

- las diferencias sociales existen de manera «natural», y son «asimiladas» por la escuela, ya sea vía diferenciación entre estudiantes «aventajados» y «desaventajados», vía expulsión escolar directa — llamada, con gentileza, «deserción escolar» — , o vía diferenciación en los tipos de escuelas, en atención a diversos criterios — escuelas técnicas o de oficios, escuelas religiosas, escuelas privadas de pago, escuelas para niños pobres, entre otras — .

- la escuela es un mecanismo de ascenso social, de movilidad, que, al preparar «para la vida», realiza una «inversión» en ¡capital humano! [Para que no nos llamemos a engaño, en el año 2000, un documento de la ¡Unesco!, conocido como Informe Delors, se llama, en realidad, La educación encierra un tesoro. Y bien que sí, ya lo saben en la OMC y el Banco Mundial que vigilan los índices de escolaridad con la misma atención que el PIB.] En esta versión de la escuela como inversión, o como bien de consumo — que hay para todos los gustos y posibilidades… económicas — ; la educación es una mercancía, susceptible de ser privatizada, sino en todo, por partes. Lo curioso es que ciertos sectores de la izquierda han «comprado» este discurso de la educación como un «tesoro», una «inversión», que produce «capital humano». En rigor, se ha de apuntar, que ha sido vendida — y no ha tenido poca aceptación en el «mercado» — esta idea a países empobrecidos como un «boleto» para salir del subdesarrollo estructural, sobre la base de la presunta posibilidad del mismo para «capacitar la mano de obra» que necesita la economía trasnacional. [En este punto, como otra aparente digresión, he de anotar que esta concepción de escuela y de educación, no es, ni con mucho, «memorística», ni «mecanicista» ni, en apariencia pasa por «autoritaria», ni produce «dolor emocional»; antes bien, impulsa la «creatividad», las «competencias», las «destrezas», las «habilidades» técnicas y «emocionales», busca… ¡la «educación integral»!]

Un análisis detallado de las anteriores características y, sobre todo, de sus reales gradaciones en la práctica; permiten, en principio, apuntar que:

- no hay «una» escuela tradicional, sino múltiples

- cualidades de la escuela tradicional pueden ser la memorización y el autoritarismo; pero solo eso, pueden ser. De hecho, en las «versiones» más contemporáneas de la escuela, hay poco de memorística, y el autoritarismo ha sido sustituido por formas más sutiles de dominación — en el mejor de los casos se ha intentado crear una «burbuja» que deja el autoritarismo «fuera» de la escuela; y en el peor, se ha llegado a confundir autoridad con autoritarismo, llamando a «experimentos» de supresión de toda organización — . Cierto sector de la izquierda ha asumido que la autoridad es per se algo perverso, germen de la tiranía. Confundir autoridad con autoritarismo es como confundir el fondue de queso con el queso fundido.

La reacción frente al autoritarismo es lógica, pero no basta para llenar un proyecto educativo distinto, diferente, no solo opuesto al del capitalismo.

Aquí sucede algo parecido con la cuestión de la consideración de la escuela como «aparato ideológico del Estado»: el origen de la confusión está en la concepción que se tenga de la organización de la sociedad y el papel de los dirigentes. Se ha puesto muy de moda la concepción de «movimientos» que pretenden ser más «horizontales» que un ángulo de 180º, y tal idea se ha pretendido llevar a la educación — ¿o fue de ciertas corrientes educativas que salió esa concepción? — . Pero la práctica ya ha demostrado dónde terminan esas ideas.

La crítica a la «escuela tradicional» desde la izquierda: algunos equívocos

La escuela tradicional ha sido criticada desde su propio nacimiento, y a la misma se le han opuesto numerosos movimientos que han tenido mayor o menor éxito, en dependencia de determinadas condiciones. En algunos casos, las «contraescuelas» — por ejemplo, las «Montessori» — han sido «absorbidas» por el movimiento revolucionario del turbocapital y la han hecho parte del sistema dominante. En otros casos, «nuevas escuelas» y «nuevas pedagogías» — por ejemplo, la soviética y las de su inspiración — que ocuparon un espacio hegemónico importante desaparecieron bajo oprobiosas acusaciones — con razón en algunos asuntos, dígase con pena — . En no pocos ejemplos, se han mantenido, de manera «marginal», algunas experiencias «contraescolares» — «escuelas» de inspiración anarquistas, por poner un caso — .

Una de las cuestiones más comunes en la crítica, desde la izquierda, a la escuela — y que ya veremos, ha sido, en los últimos decenios, un discurso muy afín a las pretensiones de la derecha — es el de su conflictiva relación con el Estado. Ello pudiera explicar que, no pocas de las posiciones se han ubicado en un ámbito antinstitucional, como expresión de un posicionamiento antiestatalista.

Con probabilidad, uno de los asuntos más censurables de la crítica que se hace desde cierta zona de la izquierda es aquella que reduce la Ilustración como el movimiento que fundamenta, en términos ideológicos, la educación o los «mitos educativos», a partir de dos argumentos esenciales: la escuela como camino hacia una sociedad de «iguales» — por oposición a la sociedad estamental, típica de las formaciones precapitalistas — y la escuela como espacio de igualdad de oportunidades. Aquí solo cabe decir que ambos argumentos no son incorrectos, a lo sumo, son incompletos — y, de paso, que el proyecto educativo de la Ilustración no se reduce, ni con mucho a lo anterior, pero eso es asunto de otro momento — . Lo que no alcanzó la educación de la Ilustración no ha sido por exceso de aquella, sino, en rigor, por su falta; de la misma manera que lo que tuvo de burguesa la revolución francesa fue su ¡contrarrevolución! [Dicho sea de paso, las recordadas críticas que los «padres fundadores» de la nación cubana hicieron a la educación decimonónica se basaba, en rigor, en los términos y fundamentos de la Ilustración.]

En esta visión, la escuela misma es un límite a la capacidad de crecimiento y mejoramiento humanos, al convertirse en un sistema-monstruo, atado a intereses estatales o privados — otro ¡Leviatán! indomable — . Considerar, a la altura del siglo xxi, que, los indudables logros que la clase trabajadora ha arrancado a la burguesía durante los últimos doscientos cincuenta años en materia de educación masiva, pública y con ciertos mínimos de calidad, es parte de una perversa conspiración para darle más poder y afianzar al Estado, es, cuando menos, un desvarío.

Lo que sucede es que no pocos quieren pedirle «peras al olmo», y que la escuela resuelva lo que no ha podido resolver, por sí misma, la sociedad. [Por eso, entre otras razones, no bastaba con el «tengamos el magisterio y Cuba será nuestra», de don Pepe de la Luz y Caballero; hacía falta una revolución de sacrificio masivo para hacer «Cuba nuestra», y aun así no alcanzaron los primeros treinta años.]

En relación con la concepción presente en las críticas, desde la izquierda, al Estado como un instrumento de dominación, como un medio institucionalizado con el cual se impone, se inculca y se legitima los intereses de la clase dominante comentaremos en el epígrafe siguiente, dada su centralidad en el asunto.

Sobre la escuela como Aparato Ideológico del Estado

Como ya he apuntado al inicio, al parecer los enemigos del marxismo no tienen que dedicarse mucho a combatirlo cuando, en nombre del propio marxismo — y con más ahínco que aquellos — , una parte no despreciable de los marxistas se dedican a defender lo mismo que defienden sus enemigos. Hay múltiples ejemplos, pero, el relacionado con la escuela — como institución pública — es paradigmático.

Y esta confusión parte de una confusión mayor: la concepción del Estado. En relación con el Estado moderno — entendiendo como tal el de la época del capitalismo — , no poco de la tradición marxista ha fallado en delimitar varias cosas: desde qué es, de verdad, el Estado, hasta cuál es la diferencia entre Estado, como sociedad política y la sociedad civil, y cuáles son las diferencias entre el poder del Estado y el aparato del Estado, por hablar de algunos casos; Marx dejó esbozadas algunas ideas, Lenin, en lo que pudo las continuó, pero más allá de Gramsci no ha habido un desarrollo, esencialmente nuevo. Uno de esos fallos ha sido al delimitar dónde comienza la Ilustración y dónde el capitalismo — sí, porque aunque algunas personas les cueste trabajo creerlo, el derecho de las masas populares a participar, incluso donde ha sido apenas a nivel representativo, de la vida política de la nación, no fue un dócil regalo de la burguesía empoderada, ha sido, como otros tantos derechos, arrancado con no pocas luchas; y en algunos lugares, todavía hoy, ni eso — ; en el entendido perverso de que Ilustración y capitalismo son dos caras de la misma moneda. La cuestión no es menor porque las confusiones entre el proyecto de uno y otro y la presunción de que el Estado moderno era consustancial del capitalismo económico — su «superestructura» — regaló a los enemigos del marxismo un caudal teórico — sin contar realizaciones prácticas — del que aun adolecen todos los que se ubican en un «antiestatalismo», que presume de izquierdas — y en rigor histórico hay que reconocer que no mejor les fue a los que intentaron ir «más allá del Estado y del derecho», yendo justo a más Estado y más a la derecha — .

Dentro de los regalos que aceptó cierta zona de la izquierda está el concepto de «aparatos ideológicos del Estado» — en su versión althusseriana — , como una explicación que, aplicada a la escuela, permitiera desmontar una de las más grandes conquistas de las revoluciones de los siglos xviiiy xix: la educación pública. [Y quizás en 1968, en medio del mayo francés, parecía el asunto muy pertinente; pero en 2019 ya no «cuaja» la historia.]

En resumen, el concepto de «aparato ideológico del Estado» entiende que la escuela es, en los sistemas modernos capitalistas, lo que la Iglesia fue al feudalismo: es decir, un lugar donde se enseñan siempre ciertas «habilidades» — «competencias» pudieran decirse, para estar a tono con las circunstancias — , pero mediante formas que aseguran el sometimiento a la ideología dominante. No pocos podrán suscribir con entusiasmo esta afirmación superficial que, sin embargo, deja por fuera la cuestión del carácter público-estatal de la escuela moderna republicana, básico en su origen. En la modernidad — en la capitalista, pero también en la de la transición socialista — , los «aparatos» público-estatales están imaginados, como «aparatos» republicanos, quiere esto decir, antimonárquicos, anticlericales — no, en rigor, «antirreligiosos» — y antidespóticos. Ahora bien, entender que la sustitución, sin más, de los «aparatos ideológicos» feudales por los burgueses fue el resultado «natural» en el proceso de consolidación de la modernidad es pasar por alto que si ello sucedió así no fue a causa del éxito de la Ilustración, sino por su derrota.

En rigor, no es posible hablar, en abstracto, de «aparato ideológico del Estado», sin caracterizar, como mínimo, qué Estado es al que hace referencia. En un Estado republicano, la escuela pública es, justo, la vacuna necesaria, la «cura en salud» frente al «control ideológico» — y aquí se abriría otro debate sobre qué entender por «control ideológico» y por qué no refiere lo mismo que «hegemonía», pero, igual, es una deuda para saldar en otro momento — . Lo público-estatal es, hasta el día de hoy, el único antídoto que se ha encontrado contra el «control ideológico» privado, incluyendo el de los padres y las sectas religiosas, políticas y gremiales. Cualquier solución que no sea enseñanza estatal-pública, será enseñanza privada y privatizada para determinados estratos — sean estos determinados por su poder adquisitivo, su pertenencia ideopolítica, su origen territorial, étnico, racial, y otras de las agrupaciones posibles — ; cualquiera de ellos, incluso, muy disfrazados de métodos educativos «contemporáneos», «integrales», «democráticos», «horizontales» y «libertarios». Los experimentos, en uno y en otro sentido, a lo único que conducen son a formas de «privatizar» la educación — que no significa, en rigor, que sea «no-gratuita»; puede haber educación gratuita «privatizada» — . Si un grupo ultraizquierdista — o izquierdista a secas — decide desertar de la enseñanza estatal para tener su experimento de enseñanza «diferente», «libertaria», no es menos «control ideológico», ni menos nocivo que si los testigos de Jehová, los miembros de la Iglesia Católica Romana, el Talibán, los de la Alianza Evangélica, o los «nuevos ricos» decidieran hacer su propio experimento de enseñanza «distinta» — y no es que estos grupos no hayan hecho ya sus «experimentos» educativos; o que, ahora mismo no reclamen tal oportunidad — . [Como un paréntesis en este punto, se puede añadir que han existido ejemplos notables de experiencias educativas progresistas que procuraron y lograron en lo posible evitar tales defectos y alimentan nuestro caudal de la pedagogía crítica; y que, ante el panorama actual de la educación escolarizada, engrampada por acción u omisión en una crisis tremenda, no es que falten ganas de crear una «nueva escuela», pero eso es «harina de otro costal».]

Cada vez que se lanza un dardo contra la enseñanza estatal se hace en nombre de la «libertad de escoger» el «tipo de educación» y en el entendido — por algunos — de que la escuela estatal es un «germen de dictadura». Como ha apuntado alguien: «Lo malo no es que la escuela sea estatal, lo malo es que el Estado no sea un Estado de derecho». [Y en una pequeña digresión sobre la «libertad de escoger», no es ocioso apuntar que el abuso de la misma, en materias de interés público como la salud ha conducido, entre otros desvaríos, a los «movimientos» antivacunación y de ahí, en conjunto con otros factores, a la reemergencia de enfermedades que se pensaban erradicadas; y no fue en lugares de «atraso cultural».]

Ahora bien, ¿cómo impedir, en las condiciones de una sociedad en transición como la cubana, que las escuelas público-estatales devengan en «aparatos ideológicos»? Es un desafío tremendo, porque los caminos recorridos no han hecho, en no pocos casos, el mejor favor a ese propósito y porque más allá de determinadas certezas de principio, no todo está claro en términos de organización práctica.

Dos ideas básicas pudieran ser:

- la existencia — real y no formal — de un Estado de derecho socialista: y esto quiere decir cosas que no se agotan en el «Estado de derecho burgués», incluso, quizás, ni siquiera en el «Estado de derecho» y punto. Quiere decir, imperio de ley, y que nadie — ni una persona, ni un grupo de personas — , puedan ocupar el lugar de las leyes. Para ello hace falta concebir una teoría de la dominación en el socialismo — porque está claro que existe dominación en el socialismo, pero sería, en términos teóricos y, sobre todo en términos de política real práctica muy necesario entender cuáles son sus manifestaciones y límites reales, posibles y necesarios — . La escuela es como un pequeño Estado, y como tal funciona: puede ir desde la más abierta dictadura a la más perfectible democracia republicana; en el espectro entre ambos puntos y en ellos mismos, muchas personas se encuentran cómodas por lo que habrá quienes no se inmuten con que la escuela funcione de manera despótica, pero una sociedad que busca una ciudadanía responsable que participa del poder del Estado — mientras exista el Estado, para cuando este no exista, habrá que ver — , la escuela debería ser el «reflejo adelantado» de la sociedad.

- la consideración del magisterio y el profesorado como una clase de propietarios especiales: de propietarios de sus puestos de trabajo, en asociación libre y organizada en las instituciones público-estatales llamadas escuelas, sujetas a control popular. A esta clase de «propiedad» no se accede por privilegios de estrato, sino por oposición pública que garantice la presencia de los más capaces para ocupar ese cargo. El corolario de esta idea es la llevada y traída «libertad de cátedra», que tiene un «mapa» claro de los «límites» de la libertad y es el que establece la Constitución de la República. [Y habrá siempre una relación conflictiva entre los grados de libertad que impone la Constitución — o la práctica misma de la política en Cuba — y la libertad que se pueda experimentar en una escuela; lo que es poco probable que haya es una relación en forma de función lineal que empareje los límites de la libertad en uno y otro espacio.]

Estaba tentado a terminar con un decálogo — en realidad mucho menos de diez — ideas sobre cómo superar una educación autoritaria en las condiciones de Cuba, como país en transición socialista. Luego recordé que tales pretensiones — las de condensar un listado, unos requerimientos mínimos — pueden ser tan peligrosas y autoritarias como justo dicen no ser. Por eso, se me ocurrió que, con probabilidad, serían más útiles algunas interrogantes, para seguir el debate y, quizás, contribuir al propósito de educar en y para la libertad:

¿cuál debe ser la naturaleza de la relación entre el Estado socialista de derecho y la escuela cubana? ¿dónde se regulará tal relación? ¿quiénes controlarán su cumplimiento exitoso, cómo?

¿cuáles son los contenidos — en el sentido más amplio posible — de una educación en y para la libertad? ¿cuáles sus métodos?

¿cómo se forma el magisterio y profesorado para tales propósitos? ¿qué papel desempeña la «sociedad» — la civil y la política — en ese empeño?

¿qué papel se le reserva al estudiantado en su proceso de formación? ¿cómo lo ejerce?

¿cómo se mide el impacto de la educación en la sociedad?

¿cómo ensayar, desde la escuela, el alcance de una sociedad con la mayor suma de felicidad posible?

Fuente: http://www.rebelion.org/noticia.php?id=259961

Users Today : 72

Users Today : 72 Total Users : 35459978

Total Users : 35459978 Views Today : 96

Views Today : 96 Total views : 3418561

Total views : 3418561