Publicado por Álvaro Corazón Rural y Jelena Arsić

La intervención militar de Estados Unidos en Vietnam durante los años sesenta y setenta dejó como mínimo tres millones y medio de muertos. Un historiador y periodista, Nick Turse, ha denunciado en Dispara a todo lo que se mueva (Ed: Sexto Piso, 2014) que las matanzas que se produjeron en la contienda no fueron errores, sino una estrategia organizada. Al menos, los estragos que continúa causando el agente naranja con el que se defolió la selva siguen siendo escalofriantes.

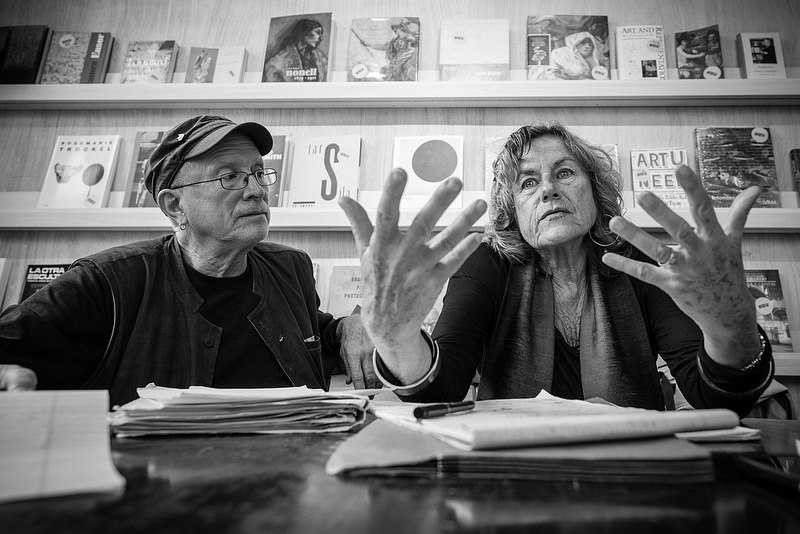

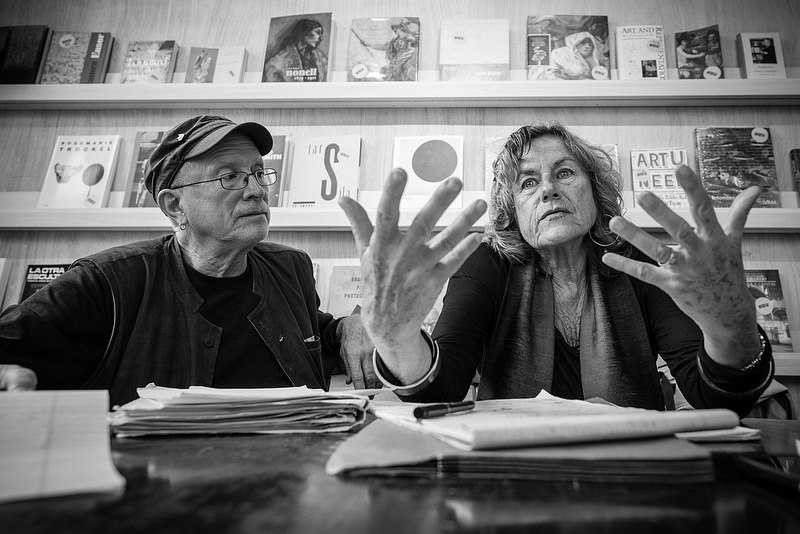

La Weather Underground fue una organización terrorista que se opuso a la guerra en la efervescencia ideológica de los años sesenta. Decidieron pasar a la acción directa, colocar bombas, para llevar el conflicto a suelo estadounidense. Siempre sin causar víctimas, las llamaban acciones simbólicas. Bill Ayers y Bernardine Dohrn fueron dos de sus militantes más destacados. Ella fue calificada por el FBI como la mujer más peligrosa de América.

Les atrapamos en un viaje que están haciendo por España presentando su nuevo libro Días de fuga (Hoja de Lata) y una novela gráfica sobre educación, Enseñar. Un viaje en cómic (Ediciones Morata). Queremos conocer sus motivaciones para llevar su movilización y su lucha a la clandestinidad, si creen que consiguieron algo y si se arrepienten de alguna cosa. Que nos cuenten su vida.

Vuestros padres son de la generación que vivió la Gran Depresión y la II Guerra Mundial. ¿Qué os contaban de aquella época?

Bernardine: Sufrieron. Mis abuelos, a los que yo nunca conocí, eran todos inmigrantes de Suecia, Rusia y Hungría. Imagínate lo que pasaron. Una experiencia tan dura como esa sirvió para que luego solo quisieran vivir con humildad y no dejar nunca de ahorrar.

Bill: Esa época fue tan sumamente dura que nuestros padres no querían ni hablar del tema, nunca mencionaban nada sobre el pasado. Como desde que nosotros nacimos todo había ido más o menos bien, ya estaba. Punto y aparte. Era un comportamiento que formaba parte de la cultura del momento: todo está bien ahora, vivimos sin grandes dificultades, así que no vamos ponernos ahora a hablar de recuerdos desagradables. Querían olvidar.

Bernardine: Y no solo fue la Gran Depresión, sobre la II Guerra Mundial crecimos sin que nos dijeran tampoco demasiado.

Bill: El inicio de los años sesenta que vivimos nosotros fue una época privilegiada, pero también de negaciones. Digamos que estábamos sumidos en un sueño profundo, no tenías conciencia de lo que había fuera de tu casita. Era todo como muy tranquilo… [risas].

El american dream.

Bill: Eso que llamaron american dream era en realidad un gran letargo en el que estábamos todos sumidos. Fue un fraude, pero era lo que había. Por eso cuando cumplimos dieciséis años y explotó el movimiento de liberación negro, a mi generación se le abrieron los ojos, apareció otro camino al margen del convencional, podías tomar la decisiones distintas sobre tu vida, elegir algo completamente nuevo.

Bernardine: Para mí empezó todo con un profesor en el colegio que nos hizo escribir sobre la guerra de Independencia de Argelia. Investigué y descubrí lo que era una guerra colonial, las torturas y demás… De modo que cuando luego entré en la facultad entendí rápidamente el significado de los movimientos por los derechos humanos que estaban apareciendo a nuestro alrededor.

Bill: También hubo una cosa más en los sesenta, el rock and roll y el béisbol. Los únicos dos ámbitos de la cultura popular donde podías ver que los negros existían.

¿El rock and roll fue una verdadera revolución?

Bernardine: Sí, en primer lugar porque los músicos eran negros. Luego aparecieron Elvis y otros blancos, pero la cultura negra estaba detrás del rock and roll. Con el rock entendimos el significado de la sensualidad en una sociedad muy reprimida.

Bill: Que el rock and roll estuviese inspirado en la cultura negra fue fundamental para romper la barrera que existía entre blancos y negros. Es interesante cómo el arte puede derribar muros hasta entonces infranqueables y enseñarte cómo es realmente la vida, el mundo y las posibilidades que tienes como persona. Tras el rock todo fue más vibrante, más intelectual, más creativo y de eso trata una revolución, ¿o no? Es un cambio político, pero también cultural, psicológico, imaginativo…

¿Cómo percibíais lo que era el capitalismo antes de entrar en contacto con los movimientos sociales?

Bernardine: Yo ni sabía lo que era el capitalismo cuando estaba en el colegio ¿Y tú, Bill? Algo sí, ¿no? Porque tu padre era capitalista… [risas].

Bill: Yo estaba en un colegio interno de cierto nivel y en las clases de Historia teníamos que leer a Marx, pero por supuesto desde la interpretación de que sus ideas conducían a la esclavitud. Sin embargo, solo con algunos puntos uno ya podía deducir que la vida era distinta de lo que nos habían enseñado. Recuerdo cómo nada más leerlo le pregunté a mis padres por qué teníamos una asistenta y por qué ella ganaba menos que mi padre. Mi padre me contestó que él trabajaba mucho para conseguir su sueldo y yo le contesté que la asistenta también trabajaba duro [risas]. ¿Cuál era la diferencia entonces?

¿De qué iban las primeras manifestaciones a las que asististeis?

Bernardine: Las primeras manifestaciones a las que yo fui fueron antinucleares, cuando iba al instituto. Recuerdo ir, alucinar con la que estaba montando la gente que tenía alrededor y no saber ni lo que había que hacer.

Bill: Ir por primera vez a una manifestación suponía romper con la comodidad del pasado. Eso era muy excitante. Aunque también daba miedo salirse de repente de lo que para ti había sido hasta ese momento la «vida normal». Y el hecho de que las primeras manifestaciones a las que fuimos fueran antinucleares es interesante porque, primero, nos dimos cuenta de que el único país que había usado ese armamento era el nuestro y eso era muy duro de asumir. Se supone que nosotros éramos los luchadores de la libertad, los que traíamos la paz, pero fuimos nosotros los que tiramos esas bombas en las ciudades japonesas.

Bernardine: El mes pasado me fui de viaje con mi hijo a Hiroshima y volví a sentir una indignación que no te la puedes ni imaginar.

Bill, lo dejaste todo y te enrolaste en la tripulación de un barco mercante.

Para mí supuso una gran experiencia. Estuve por primera vez en contacto con la clase trabajadora, un tipo de personas con las que nunca antes había convivido. Hacerme amigo de ellos fue genial, era uno más entre blancos y negros. Lo más didáctico de la experiencia fue comprobar que el propio barco estaba organizado como la pirámide social que dejábamos en tierra. Los negros hacían las labores más ingratas, los marineros algo cualificados eran de todo tipo de origen y los oficiales, todos blancos.

Cuando regresaste del barco empezó tu militancia.

Bill: No fui un militante precoz. Tardé en tomar conciencia. En esa época estaba estudiando Derecho y todos los estudiantes éramos blancos y todos menos seis chicas éramos hombres. Empecé a acercarme a movimientos sociales por afinidad, pero lo que supuso un verdadero cambio fue que Martin Luther King vino a Chicago. Antes, no reuní el valor suficiente para irle a ver al sur, pero cuando apareció por mi ciudad pensé que iba a arrepentirme toda mi vida si no me involucraba. King vino con diez activistas del sur. Nos preguntó a mí y a otros estudiantes si sabíamos quién era el propietario de la mayor parte de los pisos que se estaban arrendando en la ciudad a los pobres. Lo investigamos y nos fue imposible encontrar nada, todo iba por compañías y no logramos dar con un nombre, con un responsable. El problema era que los pisos estaban en muy mal estado. No eran siquiera habitables. No tenían ventanas, calefacción ni agua caliente. Estaban llenos de ratas y cucarachas. Así que nos pusimos a trabajar en poner de acuerdo a los vecinos para que reunieran dinero en una cuenta y pudieran reparar los edificios.

Bernardine: También nos dedicábamos a parar desahucios. Nunca olvidaré un día muy concreto en el que no pudimos detener a la policía, fallamos, y lograron entrar en el piso de una familia. Hacía mucho calor, recuerdo. Y los agentes empezaron a bajar los muebles, su ropa, las cosas de la cocina. La gente se puso muy furiosa, cada vez más. Yo estaba ahí metida en mitad de la masa rabiosa cuando de repente me empujaron, alguien enorme, miré arriba y se trataba de Muhammad Ali. Él me miró también, me pidió que le sujetase su chaqueta azul de mil dólares, se fue directo a los muebles que estaban tirados en la acera, cogió un sofá, se lo echó al hombro y lo volvió a subir al piso. Cuando la gente le vio hacer eso alucinó. Nos pusimos todos a imitarle y subimos las pertenencias de esa familia de vuelta a su hogar. La policía entonces volvía a cargarlas y las bajaba otra vez, pero, conforme las dejaban en la acera, nosotros las volvíamos a subir. Fue increíble. La acción directa en los barrios negros para mí fue una gran experiencia. Muchísimos vecinos se dirigían a mí a preguntarme cómo librarse de la guerra de Vietnam. Hubo un momento en el que empezaron a juntarse los mismos problemas: el racial, la pobreza y la guerra. Al final de verano ya empezaron a presionar a King para que se marchara de Chicago.

Bill: Ese gesto de Muhammad Ali de volver a subir el sofá y lo que supuso ha llegado hasta hoy. La gente se sigue oponiendo a los desahucios y hemos conseguido que muchos policías se nieguen a ejecutarlos.

El pretexto de Estados Unidos para su intervención en Vietnam fue la Teoría del Dominó. ¿Qué opinión os merece?

Bernardine: El capitalismo le tenía pánico a la revolución social en el tercer mundo. China y Vietnam les aterraban incluso más que la Unión Soviética por la cuestión latinoamericana y lo que les había sucedido en Cuba. Se sentían amenazados. Pero no creo que ellos se creyeran la Teoría del Dominó tal y como la formularon. Para ellos, más bien, con la demostración de fuerza que hicieron sobre Vietnam, persuadían a los demás países de no llevar a cabo una revolución social.

Bill: Para mí la Teoría del Dominó fue un mito en muchos aspectos. Aunque como metáfora era válida: la liberación nacional, el antiimperialismo, la emancipación de los trabajadores eran ideas peligrosas para el poder que no debían extenderse. Incluso tres años después de la ocupación de Vietnam, aunque estaban perdiendo, seguían matando; seguían los campos de concentración en el sur, arrasaron la poca infraestructura que el país pudiera tener. ¿Y por qué, para qué? Para que cuando los demás países vieran cómo había quedado Vietnam de destruida se lo pensaran dos veces antes de intentar ser libres, que liberarse tenía un precio inasumible. Y efectivamente, al final Vietnam ganó la guerra, pero las pérdidas fueron enormes.

Tengo aquí el libro de Nick Turse, Dispara a todo lo que se mueva. Es un estudio que detalla todos los crímenes que se cometieron allí. ¿En los sesenta teníais acceso a esa información?

Bill: Ese libro es fantástico. Explica perfectamente lo que ocurrió en Vietnam: Un genocidio.

Bernardine: La información nos llegaba a través de periodistas jóvenes que iban a cubrir la guerra. Sabían que las autoridades estaban mintiendo sobre el desarrollo de la guerra, en especial con las cifras de muertos. Por otro lado, teníamos a los soldados. No eran profesionales, eran de reemplazo, de leva, fueron obligados a ir. Y esta gente cuando volvía te contaba todos los horrores de la guerra de los que habían sido testigos. Contaban la verdad. Con lo que revelaban los periodistas y los veteranos ya sabíamos que estaban masacrando a miles de personas. Por eso se generó un pánico a la guerra, muchos jóvenes sabían que tarde o temprano iban a ser reclutados para ir a esa barbaridad.

¿Sabíais también lo de los campos de refugiados que, de facto, terminaban siendo campos de concentración?

Bernardine: Sabíamos algo, pero en realidad esa información no salió hasta 1969.

Bill: También obteníamos mucha información de Francia, de Europa, donde se contaba la guerra desde otro punto de vista.

Bernardine: Yo conocí vietnamitas en viajes que hice a Canadá y Cuba. La verdad es que llegó un momento en el que estábamos tan apasionados que llegamos a obsesionarnos con el conflicto de Vietnam. Teníamos mapas colgados en las paredes de casa, cocinábamos platos vietnamitas, leíamos a sus poetas. Llegamos a sentirnos muy identificados con ese pueblo. Por cierto, que en uno de estos viajes, conocí a un revolucionario español. Fue la primera persona que conocí que vivía en la clandestinidad.

Bill: Con toda la información que recibimos, al dejar de estar bajo la esfera de influencia del New York Times, tomamos conciencia de cuál era la situación real y nos propusimos como compromiso mostrar a nuestros compatriotas cuál era la cara humana de los vietnamitas, hacerles ver que se trataba de gente normal, con sus familias y sus amigos, y no una especie de seres extraños.

¿Habéis visto la entrevista a Robert McNamara de Errol Morris?

Bernardine: A mí McNamara me saca de quicio. Verle llorar en esa entrevista…

Bueno, él cuenta tranquilamente cómo lanzaron miles de bombas sobre la población civil japonesa, cómo arrasaron Vietnam. Admite que murieron cientos de miles de personas por sus decisiones, que podría ser considerado un criminal de guerra, pero con lo que llora es cuando recuerda el asesinato de Kennedy.

Bill: Esa es su personalidad. Es uno de esos hombres que piensan todo en términos de números y categorías. Incapaces de pensar en términos de seres humanos que tienen sentimientos. Pasa lo mimo con Kissinger, que acaba de sacar un libro y en el New York Times hablan de él tranquilamente, como si fuera un intelectual más, cuando es un criminal de guerra. Posiblemente uno de los más grandes del siglo XX. De hecho, no puede viajar a ciertos países porque lo meterían en la cárcel, pero en Estados Unidos se le considera como un cerebro privilegiado de la política exterior. Lo que demuestra que es muy fácil justificar torturas, asesinatos, bombardeos y matanzas de civiles cuando eres tú el que las cometes. Si las hace otra persona entonces resulta que es terrorismo. McNamara y Kissinger son dos ejemplos de ese nacionalismo repugnante. Y ahora, en la actualidad, tenemos a John Kerry como ejemplo de esa brillante línea de pensamiento.

Bernardine: Aunque eso no quita que para nosotros siga siendo muy importante apoyar a los veteranos de guerra. No solo a los que cambiaron su opinión, sino también a los jóvenes que han pagado un precio muy alto por entrar en combate pensando que están cumpliendo con su deber o con una obligación moral. Además, muchos de ellos fueron a Irak o Afganistán respondiendo al 11S, y una buena parte solo para poder conseguir una vía económica para financiar sus estudios universitarios. De repente se encontraron metidos en una guerra de once años de duración…

Bill, en tus memorias, comentas que la primera vez que te pegó la policía te sentiste «en el paraíso».

Bill: Es una ironía, pero fue así. Nunca me había sentido tan libre. Es difícil de explicar. Cuando estuve en la clandestinidad, por ejemplo, también tenía miedo, pero la sensación de libertad que sentía era más intensa que si me encontrase como un ciudadano más. Aunque te pegue la policía o te detengan, cuando te defines ideológicamente, cuando tomas tu elección de vivir por una causa superior, te emocionas tanto que los golpes no los sientes, aunque te puedan doler.

Llegas a decir en tu libro que en la cárcel no podías sentirte más libre.

Bill: En la celda me sentía más libre que los que están en su casa viendo la televisión zampando del frigorífico. Os lo aseguro. Y no solo yo. Leí que entre los miembros de la resistencia francesa, tras la II Guerra Mundial, sentían que al acabar la guerra habían perdido su tesoro, el subidón de libertad que es la lucha clandestina. Se habían quedado vacíos tras perder el motivo de su lucha. Suena duro, pero ellos estaban plantándoles cara a los nazis, contraatacándolos, y cuando eso se acaba, te debe absorber de tal manera que parece como que has perdido algo.

Bill, por curiosidad, en tus memorias citas mucho Ann Arbor. Por aquellos años, en esa ciudad, estaba el grupo MC5. ¿Les conociste?

Bill: Sí, claro que sí. Éramos muy buenos amigos de John Sinclair, su manager. Cómo olvidar que le metieron diez años de cárcel por llevar encima dos porros. Él predicaba que la marihuana era una forma de liberación y se lo hicieron pagar. Los MC5 estaban llenos de energía, además era un grupo mitad político, mitad rock and roll, eso era muy inspirador. También andaba por ahí Iggy Pop, pero MC5 estaban siempre tocando en todas las fiestas que organizábamos. Luego solíamos terminar con ellos en la cocina bebiendo vino y fumando marihuana, hablando tranquilamente. Eran muy buena gente y muy buenos amigos.

Os sentíais parte de una revolución global contra el capitalismo.

Bernardine: Claro, nos sentíamos identificados con los movimientos de descolonización africanos, seguíamos de cerca la guerra de liberación de Angola. Apoyábamos la lucha del pueblo vietnamita. Estábamos con los movimientos pacifistas de todo el mundo. Considerábamos que la lucha del tercer mundo era la nuestra, solo que nosotros la librábamos desde dentro.

Bill: Luchábamos por la descolonización, éramos antinucleares, pacifistas, estábamos con los movimientos negros y creíamos que Estados Unidos era responsable de todos los problemas contra los que luchábamos.

Qué opináis de las nuevas generaciones, ¿son tan combativas como la vuestra?

Bernardine: Son mucho más globales de lo que nosotros éramos. Nosotros hicimos un cambio, digamos, hacia una mentalidad internacional. Pero ellos han crecido pensando de forma internacional. También creo que leen mucho y que están muy bien informados. Veo que son muy inteligentes. Mira cómo se organizaron este verano cuando la policía mató a un chico negro en San Luis. También han hecho triunfar a los movimientos gay…

Bill: Sobran los ejemplos. Ahora mismo hay jóvenes luchando por los derechos de los inmigrantes, por los derechos de las mujeres, contra la violencia de la policía, por el medio ambiente. No se puede comparar. Los años sesenta se han mitificado. Hay quien dice que en esa época pasaron todas las cosas buenas. La mejor música, las mejores manifestaciones, el mejor sexo. Y nosotros siempre respondemos que no, que el sexo sigue siendo bueno [risas]. No, incluso aún hay buena música y muchas cosas interesantes. Que no se engañe a los jóvenes metiéndoles en la cabeza que todo terminó con los años sesenta.

Bernardine: Los jóvenes cambian el mundo. Pasó en nuestra época, pasó después y ocurre ahora. Aunque haya una represión masiva, siempre son los jóvenes los que protagonizan los cambios. En nuestros tiempos, los medios siempre decían que los movimientos estudiantiles estaban muertos. Hasta en el año 68 lo decían, mientras el mundo explotaba y no encontrábamos espacios lo suficientemente grandes para poder reunirnos.

Bill: El poder siempre hace eso. Primero ignora al movimiento y luego lo ridiculiza.

En vuestra época había un libro de Mao en cada cajón de cada mesilla.

Bill: Sí, en algún momento todos tuvimos nuestro pequeño romance con el maoísmo. Pero para nosotros el Partido Comunista nunca fue interesante. Tampoco nos considerábamos una nueva izquierda. No éramos anticomunistas, no nos importaba que nadie viniese a nuestra organización siendo comunista.

El nombre de vuestra organización venía de una canción de Bob Dylan.

Bernardine: Estaban siendo asesinados seis mil vietnamitas por semana y la policía estaba asesinando a los miembros destacados de los Panteras Negras. Discutimos en una reunión de urgencia qué estrategia seguir y redactamos un documento de muchas páginas, como un informe interno de la organización. Después de leerlo, teníamos que ponerle un título y Terry Robins, gran fan de Bob Dylan, eligió ese título.

La primera norma de vuestra organización: sexo libre.

Bernardine: No fuimos solo nosotros. Pasó en muchos movimientos. Las píldoras anticonceptivas acababan de cambiar nuestros esquemas morales sobre el sexo, que la mujer podía tener placer formaba parte de su liberación. Dimos un paso adelante rechazando la monogamia.

Bill: Pensábamos que todo lo viejo, lo antiguo, lo anterior, tenía que ponerse en duda. Digamos que fue una idea experimental.

Bernadine: Pero no fue inútil. Con la propuesta del sexo libre muchos se encontraron a sí mismos; muchos amigos nuestros, por ejemplo, descubrieron que eran gais. Funcionó de maravilla porque conseguimos que cada uno fuese capaz de vivir su propia sexualidad, que es diferente en cada persona. Yo no quería casarme nunca [risas] y aquí estoy, pero porque consideraba que el matrimonio suponía para las mujeres convertirse en propiedad del marido.

Bill: También hay que decir en defensa del sexo libre que antes éramos jóvenes y guapos. ¡Quién quería ser monógamo!

¿Había muchos miembros de vuestra organización que provenían de familias acomodadas?

Bernardine: Había de todo. Mucha gente que vivía de familias ricas, otros eran de clase media. Otros inmigrantes. Pero en general la mayoría veníamos de las universidades, aunque también había gente que solo tenía la educación secundaria. Éramos una gran mezcla. El punto de ruptura fue cuando decidimos convertirnos en una organización que iba a vivir en la clandestinidad, a realizar acciones ilegales. Rompimos con la ley y las manifestaciones en las que participamos empezaron a ser violentas, con destrozos de mobiliario. Pero tenéis que entender que Estados Unidos es uno de los países más violentos que te puedas encontrar. En vuestra sociedad, en Europa, la gente no va armada. En nuestro contexto, estábamos ya rodeados de violencia de modo que hay que valorar en su justa medida que en nuestras manifestaciones hubiera actos vandálicos. En aquellas fechas estaban muriendo seis mil personas a la semana en Vietnam, dime ¿qué ibas a hacer, qué podías hacer para pararlo? Los grupos católicos de izquierda, curas y monjas, iban por ahí quemando cosas con gasolina. Que las autoridades nos consideraran violentos a nosotros era como de broma. Nunca matamos a nadie. Solo hicimos acciones que se pudieran entender como un mensaje.

Bill: Violencia es quedarse en casa viendo la televisión mientras fuera se cometen injusticias. La mayoría de la población americana piensa que si no hacen nada no están siendo violentos. Nosotros apoyamos la acción directa. Es otra cosa. Si le preguntas a Martin Luther King te diría que nuestra acción directa contra el militarismo o el racismo no es violencia.

Bernardine: Cuando salió el documental sobre nosotros se presentó en Sundance. Fuimos invitados al estreno y recuerdo que una periodista del LA Times nos preguntó que cómo podíamos ser violentos si nos gustaban Gandhi y Mandela. Yo le dije: ¿Cómo? ¿Mandela? En Estados Unidos la gente se piensa que fue un gentleman que estuvo en la cárcel y él solito acabó con elapartheid. Pensé: «Anda, vete a casa y lee un poco aunque sea en Google sobre lo que hizo Mandela y luego seguimos esta discusión». En Estados Unidos tenemos una imagen muy distorsionada de lo que es la verdadera violencia.

Bill: Es como cuando el presidente de Estados Unidos dice que King fue un ejemplo a seguir, un hombre recto. Y yo pienso que no, que no actuaba solo. Él era parte del movimiento. King no creó el movimiento, el movimiento creó a King.

Bernardine: Me gustan los movimientos juveniles actuales que se niegan a tener un líder.

Bernardine, el FBI dijo que eras la mujer más peligrosa de América.

Bernardine: Ya me gustaría…

Bill: ¡Esa es mi chica! [risas]

Bernardine: Antes de mí, ¿sabes quién dijeron que era la mujer más peligrosa de América? Jane Addams, una feminista que era socialista y lesbiana. Se había opuesto a la I Guerra Mundial. Edgar Hoover, que estaba empezando, dijo que era la mujer más peligrosa de América y después de unos años la dieron el Premio Nobel de la Paz [risas].

Bill: A Bernardine la pusieron en una lista de los diez delincuentes más buscados. Las listas de los más buscados habían estado siempre llenas de criminales, mafiosos, de asesinos terribles y, a partir de los setenta, se empezaron a llenar de estudiantes guapos [risas].

Bernardine: Fracasaron. Iban de organización poderosa, pero les pillamos por sorpresa. Durante años mandaron a gente a que preguntara por mí de puerta en puerta. Creían que nuestros padres o nuestros compañeros de la universidad iban a decirles algo, pero nuestra campaña de convencer a la gente de que no colaborase en absolutamente nada funcionó.

Bill: Incluso en la investigación del FBI podías ver reflejada la pirámide social. Cuando fueron a hablar con mi padre, un profesional considerado, le pidieron una cita para verle en su oficina. Cuando fueron a hablar con el de Bernardine, que era un inmigrante, aparecieron en mitad de la noche en su casa diciéndole que tenían un cuerpo en la morgue que querían que identificase a ver si era su hija. Le intentaron aterrorizar, mientras que a mi padre le guardaron una distancia y un respeto.

Bernardine: Como sabéis, una vez conseguimos robar los archivos del FBI. Ahí vimos que había dos estrategias. Para los negros, asesinar a sus líderes; para los blancos, infiltración y destrucción desde dentro.

Bill: Sí, con los movimientos negros hicieron eso, matarlos. Tardó siete años en salir a la luz, en que los abogados lograran demostrarlo, pero al final se vio que eran ciertos algunos asesinatos.

Bernardine: Pero ya os digo, nadie colaboró con ellos para atraparnos a nosotros. Porque, además, no éramos los únicos que estaban en la clandestinidad en aquel entonces. Había mucha gente indocumentada, traficantes de LSD, insumisos que huían de la mili, desertores, no estábamos solos. Estados Unidos estaba lleno de gente furtiva.

¿Cómo era la vida en la clandestinidad?

Bernardine: Trabajábamos. Yo lo hacía de camarera, limpiando casas, recogiendo fruta, vendimiando. Y entretanto, muchas reuniones. Mientras, sabíamos que parte importante de la sociedad nos apoyaba, tenían ese gran romance americano con losoutlaws, como si fuésemos Bonnie & Clyde.

Un antes y un después en vuestra organización fue cuando le explotó la bomba en Nueva York a unos militantes de vuestro grupo, una bomba que iban a colocar en un baile de oficiales para matar al mayor número de ellos posible. Ahí decidís no atentar contra vidas humanas.

Bill: Unos del grupo decidieron hacer ese ataque en una base militar. Prepararon la bomba, les estalló y murieron los tres. Pero ya habíamos pasado a la clandestinidad y esta decisión la tomó un grupo por su cuenta porque funcionábamos de forma descentralizada. De todas formas, lo que pasó en ese edificio donde explotó la bomba no lo sabe nadie. La bomba estaba hecha con metralla para matar personas, no para hundir un edificio. En lo que a nosotros respecta, cuando descubrimos lo que habían planeado, fue un shock. Estábamos muy asustados. Horrorizados. Nos reunimos para decidir si apoyábamos esa clase de violencia y, tras meses de discusiones, optamos por realizar acciones meramente simbólicas, sin víctimas. ´

Bernardine: No queríamos ser una fuerza militar, asesinar a gente, sino una fuerza política. Los que estuvieron de acuerdo se quedaron y los que no, abandonaron la organización. Nos llevó un año definirnos.

¿Qué acciones realizasteis según ese modelo?

Bernardine: Los objetivos de la Weather Underground, donde pusimos bombas, fueron todos militares. El Pentágono, comisarías… La verdad es que no tengo un atentado favorito. [risas] [Lista de todas sus acciones N. del R.]

Aparte de las bombas, organizasteis la fuga de prisión de Timothy Leary.

Bernardine: De eso sí nos arrepentimos, de no haber hecho más acciones donde estaba presente el sentido del humor como en esa, que fue una operación tan divertida. Nadie nos lo ordenó jerárquicamente, simplemente vimos que era una buena oportunidad y lo hicimos. Timothy Leary era un intelectual que experimentaba con LSD y promovía esta droga como forma de romper con las costumbres e iniciar una nueva forma de vida, encontrar una nueva manera de ver el mundo. Él tonto no era, entendía nuestra lucha contra la guerra de Vietnam y el racismo. Era un activista más. Sencillamente, estaba en la cárcel por el asunto de la droga, como tantos otros, y quería escaparse. Su gente se puso en contacto con nosotros, nos pareció bien, nos financiaron y desarrollamos el plan. Fuimos capaces de sacarle de la cárcel y del país.

¿Cómo hacíais las bombas, qué materiales empleabais?

Bernardine: De eso no hablamos.

¿Conocíais a la Baader Meinhof?

Bill: Sí, sabíamos que existía, fue un fenómeno más de los sesenta. Formaciones revolucionarias que intentaban luchar. Entonces tenías ese tipo de resistencia en todas partes, en Inglaterra, en Francia, en Japón, en Alemania, en España…

Bernardine: Pero nosotros tomamos la decisión de nunca abandonar nuestro país. Éramos hijos de América. Veíamos lo que hacía la Baader Meinhof por televisión, pero nuestras estrategias, las decisiones que tomamos, fueron diferentes.

Decís en el documental que en los setenta vuestra vida en la clandestinidad y vuestros atentados empezaron a ser como una rutina. Decidisteis dejarlo.

Bernardine: Teníamos una regla que no era muy habitual en las organizaciones que operaban en la clandestinidad. En Weather Underground los militantes podían irse cuando quisieran. No había consecuencias por abandonar. Durante los setenta unos entraron, pero también muchos se fueron. Cuando acabó la guerra de Vietnam, la cuestión de seguir siendo fugitivos se puso sobre la mesa. Hubo diferentes opiniones, unos querían seguir y otros queríamos volver a disfrutar de una vida privada normal, tener familias e hijos. Muchos lo dejaron pero se unieron al movimiento gay, otros al sindicalismo… Yo odiaba tener que rendirme y entregarme, pero Bill fue adorable y me dejó tomarme mi tiempo. Al final nos entregamos cuando nació nuestro segundo hijo.

Bill: Estábamos también deseando militar en una organización más grande. Fuimos a Chicago, resolvimos nuestros problemas legales y no entendimos que nuestra reinserción fuese en contra de nuestras ideas revolucionarias.

Bernardine: Yo hice mi discurso militante: «Me niego a entregarme, pero aquí estoy» [risas]. No sabíamos qué iba a pasar. Teníamos dos críos. Le dijimos a nuestro hijo mayor lo que pasaba y al menos se quedó con que íbamos a cambiarnos los nombres, nunca habíamos ido por ahí con los verdaderos. La noche siguiente vimos a los padres de Bill por primera vez en once años y luego fuimos a que yo le presentara a los míos.

Bill: Lo que más me gustó es que el primer comentario de mi padre al verme fue que necesitaba un buen corte de pelo. Y lo primero que dijo el padre de Bernardine fue «¿Estás casada?». Seguían siendo unos padres como los de toda la vida.

Bernardine: Ahora bromeamos con eso pero la verdad es que los pobres pasaron por un auténtico infierno. Pero bueno, llegado el momento estaban muy felices de ver a sus nietos.

¿No tuvisteis problemas con la ley?

Bernardine: Yo tenía cargos por las manifestaciones violentas, unos dieciséis o diecisiete. Cargos federales por destrozar propiedades públicas. Pero el FBI había llevado las investigaciones de forma tan claramente ilegal que no pudieron acusarnos de nada. Tampoco tenían muchas pruebas a esas alturas, la verdad. De todas formas, muchos militantes de Weather Underground sí que terminaron en la cárcel, pero por otros cargos al margen de nuestras acciones. Por no querer revelar nada sobre mis compañeros yo ya me había chupado en su momento siete meses de cárcel.

Bill: Las acusaciones fueron muy débiles. Nos acusaban de haber planeado acciones pero no tenían pruebas de que las hiciéramos. Con esas acusaciones ridículas nos habían puesto en la lista de los diez más buscados. Además, el FBI pretendía secuestrar al hijo de la hermana de Bernardine y retenerle hasta que nos entregáramos. No llegaron a hacerlo, pero con esos métodos ningún juez les hubiera podido haber dado la razón.

Bernardine: Los agentes que planearon eso terminaron condenados. Tras el final de la guerra de Vietnam y la guerra sucia del FBI América estaba en shock. Nos colamos por la puerta que abrió el presidente Jimmy Carter, aunque nos entregamos justo cuando Reagan fue elegido presidente [risas].

Hoy en día seguís recibiendo amenazas de muerte.

Bill: Es que uno de mis libros lo publiqué justo el 11 de septiembre de 2001. Esa misma mañana el New York Times llevaba en portada de su sección cultural una foto de nosotros dos con la reseña. El diario salió a las seis de la mañana y los atentados contra los Torres Gemelas fueron a las nueve. A raíz de eso, nos llovieron más amenazas que durante la guerra de Vietnam. En esos días de auténtica paranoia con el terrorismo, nosotros nos convertimos en los terroristas domésticos de Estados Unidos. Recibimos amenazas de muerte prácticamente todos los meses. Si vamos a dar un discurso a algún lado, siempre hay amenazas, pero no las tomamos en serio. Es solo gente muy ruidosa pero nada más. Nos los imaginamos como el típico tío bebiendo demasiado whisky delante del ordenador, quién sabe si viviendo en el sótano de la casa de su madre [risas].

¿Qué habéis hecho contra la guerra de Irak y Afganistán?

Bill: Estuvimos en muchos movimientos. En especial en un movimiento colectivo en Chicago [Movement Building Colective] Pero creemos que no puedes limitarte solo a estar en un movimiento ni quedarte en tu casa sentado. Hay que hacer algo más. Por eso hemos estado profundamente involucrados en proyectos pacifistas que van de la educación a la justicia, aunque la guerra sea la idea central.

Bernardine: Yo también estuve en el movimiento en contra de que la OTAN se reuniera en Chicago hace dos años.

Bill: Esas manifestaciones fueron un gran éxito. Vimos cómo el Gobierno se lo tomaba como un ensayo general para la represión. Nunca habíamos visto la ciudad tan vacía. Los únicos que quedamos fuimos nosotros, los manifestantes, y la policía y los militares. Todo lo demás, drones, helicópteros, quitanieves ¡en mitad del verano! Hacía un calor infernal, pero los trajeron.

Bernardine: Lo más impresionante es que los que más daban la cara en las manifestaciones eran veteranos de la guerra de Irak. Los líderes de estos movimientos habían estado en la guerra. Iban los primeros, encabezaban la protesta y lo más espectacular fue cuando les lanzaron sus medallas a los generales de la OTAN, fue una imagen imborrable.

Bill: Estados Unidos tiene una larga historia de ocupaciones militares y guerras. Invasiones de terceros países que no solo son injustas e ilegales, sino que además acaban con las aspiraciones de paz y justicia de todos los ciudadanos del planeta. Lo más grave de todo, además, es que las guerras por petróleo no responden a una causa política, que implique a mucha gente, sino solo a los intereses de un 1%. En este contexto, nosotros no podemos influir en el Congreso, pero sí en nuestras áreas de influencia más cercanas, como es la educación. Por eso tratamos de organizarnos de abajo a arriba. Promovemos nuestros valores en la comunidad, en las aulas, en la iglesia, en la universidad. No te creas que esto no le preocupa al Gobierno. Si miras la historia de todos los grandes cambios, siempre vienen desde abajo.

Bernardine: De hecho, en política, nunca harás nada bueno sin el poder de abajo.

¿Ha cambiado algo con Obama?

Bill: Obama en 2008 dijo que era pragmático y moderado. Pero la derecha dijo que era un musulmán encubierto, que estaba con los terroristas, que tenía una agenda socialista. Y ya veis, creo que iba en la buena dirección, pero al final no tardó en disgustarnos con todas estas guerras.

¿Os arrepentís de algo?

Bernardine: Ahora, hablando como una mujer de setenta y tres años, creo que no nos equivocamos. No me arrepiento de nada.

Bill: Nunca causamos muertos. Como dice Bernardine, no nos arrepentimos de haber causado destrozos con bombas de una forma simbólica. No nos arrepentimos de haber luchado contra un Gobierno que llevaba a cabo un genocidio en Vietnam y pretendía acabar con la cultura negra por la violencia. Con setenta años, por supuesto que me arrepiento de muchas cosas. Políticamente, el arrepentimiento más profundo que siento es el de haber formado un movimiento tan sectario. Desde ese punto de vista, tan reducido, nunca actúas bien. Ahora hemos aprendido más y crecido como personas.

Fotografía: Begoña Rivas

Enlace original en: http://www.jotdown.es/2014/11/bernardine-dohrn-y-bill-ayers-violencia-es-quedarse-en-casa-viendo-la-television-mientras-fuera-se-cometen-injusticias/

Users Today : 22

Users Today : 22 Total Users : 35461786

Total Users : 35461786 Views Today : 36

Views Today : 36 Total views : 3422514

Total views : 3422514