Harry Daniels

Department of Education. University of Oxford (United Kingdom)

El aprendizaje en culturas de interacción social

Resumen

Este artículo aborda las formas en que las culturas de las instituciones y los patrones de interacción social ejercen un efecto formativo en el qué y cómo del aprendizaje. El modo en que se regulan las relaciones sociales de las instituciones tienen consecuencias cognitivas y afectivas para aquellos que viven y trabajan dentro de las mismas. El actual estado del arte en las ciencias sociales se esfuerza por proporcionar una conexión teórica entre formas específicas, o modalidades, de regulación institucional y de la consciencia. Los intentos que se han llevado a cabo para hacerlo tienden a la incapacidad de generar análisis y descripciones de formaciones institucionales que sean predictivos de consecuencias para los individuos. Al mismo tiempo, la política social tiende a no comprometerse con las consecuencias personales de las diferentes formas de regulación institucional. Se discutirá un enfoque con el fin de establecer conexiones entre los principios de la regulación de las instituciones, las prácticas discursivas y de la formación de la consciencia. Este enfoque se basa en el trabajo del sociólogo británico, Basil Bernstein y el teórico social ruso Lev Vygotsky.

Palabras clave: Vygotsky; Bernstein; instituciones; aprendizaje; cultura.

Abstract

This paper is concerned with the ways in which the cultures of institutions and the patterns of social interaction within them exert a formative effect on the what and how of learning. The way in which the social relations of institutions are regulated has cognitive and affective consequences for those who live and work inside them. The current state of the art in the social sciences struggles to provide a theoretical connection between specific forms, or modalities, of institutional regulation and consciousness. Attempts which have been made to do so tend not to be capable of generating analyses and descriptions of institutional formations that are predictive of consequences for individuals. At the same time social policy tends not to engage with the personal consequences of different forms of institutional regulation. I will discuss an approach to making connections between the principles of regulation in institutions, discursive practices and the shaping of consciousness. This approach is based on the work of the British sociologist, Basil Bernstein, and the Russian social theorist, Lev Vygotsky.

Keywords: Vygotsky; Bernstein; institutions; learning; culture.

Introduction

This paper is concerned with the ways in which the cultures of institutions and the patterns of social interaction within them exert a formative effect on the what and how of learning. This is part of a more general argument to which I subscribe. This is that we need a social science that articulates the formative effects of a much broader conception of the social than that which inheres in much of the slew of research which emanates from the writings of Vygotsky and his colleagues. The boundaries which shape researcher’s horizons often serve to severely constrain the research imagination. Sociologists have sought to theorise relationships between forms of social relation in institutional settings and forms of talk. Sociocultural psychologists have done much to understand the relationship between thinking and speech in a range of social settings with relatively little analysis and description of the institutional arrangements that are in place in those settings. At present there is a weak connection between these theoretical traditions.

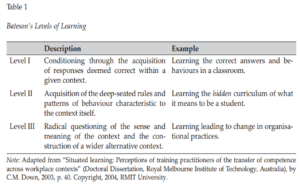

An important point of departure is with the understanding of learning itself. The Russian word, used by Vygotsky and his colleagues, obuchenie is often translated as instruction. The cultural baggage of a transmission based pedagogy is easily associated with obuchenie in its guise as instruction. Davydov’s (1995) translator suggests that teaching or teaching-learning is more appropriate as the translation of obuchenie in that it refers to all the actions of the teacher in engendering cognitive development and growth. In the plethora of approaches to the analysis of teaching and learning, whether they be situated or distributed, or espousing an internalisation, participation or transformational model, there has been relatively few attempts to forge the elusive connection between macrostructures of power and control and micro processes of the formation of pedagogic consciousness (see Daniels, 2001, 2008, for details). There also appears to be an assumption in many accounts of learning that it may be described and analysed as a homogenous phenomenon. In his original formulation of expansive learning, Engeström (1987) draws on Bateson’s formulation, in 1972, of levels of learning. Down (2003) provides a summary of Bateson’s levels as shown in Table 1.

Engeström (1987) draws attention to Learning III. He argues that this form of learning involves the reformulation of problems and the creation of new tools for engaging with these problems. This ongoing production of new problem solving tools enables subjects to transform “the entire activity system”, and potentially create, or transform and expand, the objects of the activity (pp. 158-159).

Expansive learning involves the creation of new knowledge and new practices for a newly emerging activity; that is, learning embedded in and constitutive of qualitative transformation of the entire activity system. Such a transformation may be triggered by the introduction of a new technology or set of regulations, but it is not reducible to it. All three types of learning may take place within expansive learning, but these gain a different meaning, motive and perspective as parts of the expansive process. A full cycle of expansive transformation may be understood as a collective journey through the zone of proximal development of the activity (Engeström, 1999a).

Whatever the type or form of learning that is taking place there is a need to understand its emergence in relation to the circumstances in which it is taking place. My argument is that the way forward is to be found in an exploration of the dialectical relation between theoretical and empirical work which draws on the strengths of the legacies of sociological and psychological sources to provide a theoretical model which is capable of descriptions at levels of delicacy which may be tailored to the needs of specific research questions. The development of the theoretical model along with the language of description it generates will hopefully open the way for new avenues of research in which different pedagogic practices are designed and evaluated in such a way that the explicit and tacit features of processes of the mutual shaping of person and context may be examined (Daniels, 2010). This will enable significant contributions to be made to the possibilities for studying fields or networks of interconnected practice (such as those of the home, school and community) with their partially shared and often contested objects. Alongside this enhancement of the outward reach of the theory must be increased capacity and agility in tackling inward issues of subjectivity, personal sense, emotion, identity, and moral commitment. In the past these two directions have tended to remain the incompatible research objects of different disciplines with an emphasis on collective activity systems, organizations and history on the one hand and subjects, actions and situations on the other hand (Engeström & Sannino, 2010).

Here I will consider the institutional level of social formation. I will outline an approach to the study of learning which examines the way in which societal needs and priorities and/or curriculum formations are recontextualised within institutions such as schools or universities. This approach seeks to understand, analyse and describe the structural relations of power and control within institutions and deploy a language of description to the discursive formations to which the structural formations give rise. I argue that the practices of interaction, which particular institutions seek to maintain, differentially deflect and direct the attention, gaze and patterns of interaction of socially positioned participants.

Institutions and the Social Formation of Mind

The way in which the social relations of institutions are regulated has cognitive and affective consequences for those who live and work inside them. The current state of the art in the social sciences struggles to provide a theoretical connection between specific forms, or modalities, of institutional regulation and consciousness. Attempts which have been made to do so tend not to be capable of generating analyses and descriptions of institutional formations that are predictive of consequences for individuals. At the same time social policy tends not to engage with the personal consequences of different forms of institutional regulation. I will discuss an approach to making connections between the principles of regulation in institutions, discursive practices and the shaping of consciousness. This approach is based on the work of the British sociologist, Basil Bernstein, and the Russian social theorist, Lev Vygotsky.

From a sociological point of view Bernstein (1996, p. 93) outlined the challenge as follows:

The substantive issue of . . . [this] theory is to explicate the process whereby a given distribution of power and principles of control are translated into specialised principles of communication differentially, and often unequally, distributed to social groups/classes. And how such a differential/unequal distribution of forms of communication, initially (but not necessarily terminally) shapes the formation of consciousness of members of these groups/classes in such a way as to relay both opposition and change.

The following assertion from Vygotsky (1960/1981, p. 163) recasts the issue in more psychological terms but with the same underlying intent and commitment:

Any function in the child’s cultural [i.e. higher] development appears twice, or on two planes. First it appears on the social plane, and then on the psychological plane. First it appears between people as an inter-psychological category, and then within the child as an intra-psychological category.

I argue that, taken together, the Vygotskian and Bernsteinian social theory has the potential to make a significant contribution to the development of a theory of the social formation of mind in specific pedagogic modalities.

A sociological focus on the rules which shape the social formation of discursive practice may be brought to bear on those aspects of psychology which argue that cultural artefacts, such as pedagogic discourse, both explicitly and implicitly, mediate human thought and action. Sociocultural theorists argue that individual agency has been significantly under acknowledged in Bernstein’s sociology of pedagogy (Werstch, 1998a). Vygotsky’s work provides a compatible account that places an emphasis on individual agency through its attention to the notion of mediation. Sociologists complain that post-Vygotskian psychology is particularly weak in addressing relations between local, interactional contexts of activity and mediation, where meaning is produced and wider structures of the division of labour and institutional organisation act to specify social positions and their differentiated orientation to activities and cultural artefacts (Fitz, 2007).

Vygotsky’s Sociogenetic Approach

Vygotsky provided a rich and tantalising set of suggestions that have been taken up and transformed by social theorists as they attempt to construct accounts of the formation of mind which to varying degrees acknowledge social, cultural and historical influences. There is also no doubt that Vygotsky straddled a number of disciplinary boundaries. Davydov (1995) went as far to suggest that he was involved in “a creative reworking of the theory of behaviourism, gestalt psychology, functional and descriptive psychology, genetic psychology, the French school of sociology, and Freudianism” (p. 15).

Recent developments in post Vygotskian theory have witnessed considerable advances in the understanding of the ways in which human action shapes and is shaped by the contexts in which it takes place. They have given rise to a significant amount of empirical research within and across a wide range of fields in which social science methodologies and methods are applied in the development of research-based knowledge in policy making and practice in academic, commercial and industrial settings. His is not a legacy of determinism and denial of agency, rather he provides a theoretical framework which rests on the concept of mediation. These developments have explored different aspects of Vygotsky’s legacy at different moments.

It is clear that many disciplines contributed to the formation of Vygotsky’s ideas. For example, Van der Veer (1996) argues that Humboldt with reference to linguistic mediation and Marx with reference to tool-use and social and cultural progress influenced Vygotsky’s concept of culture. He suggested that the limitations in this aspect of Vygotsky’s work are with respect to non-linguistically mediated aspects of culture and the difficulty in explaining innovation by individuals. Vygotsky’s writing on the way in which psychological tools and signs act in the mediation of social factors does not engage with a theoretical account of the appropriation and/or production of psychological tools within specific forms of activity within or across institutions. Just as the development of Vygotsky’s work fails to provide an adequate account of social praxis, so much sociological theory is unable to provide descriptions of micro level processes, except by projecting macro level concepts on to the micro level unmediated by intervening concepts though which the micro can be both uniquely described and related to the macro level.

Bernstein’s Sociology of Pedagogy

Amongst sociologists of cultural transmission, Bernstein (2000) provides the sociology of this social experience which is most compatible with, but absent from, Vygotskian psychology. His theoretical contribution was directed towards the question as to how institutional relations of power and control translate into principles of communication and how these differentially regulate forms of consciousness. It was through Luria’s attempts to disseminate his former colleague’s work that Bernstein first became acquainted with Vygotsky’s writing.

I first came across Vygotsky in the late 1950s through a translation by Luria of a section of Thought and Speech published in Psychiatry 2 1939. It is difficult to convey the sense of excitement, of thrill, of revelation this paper aroused: literally a new universe opened (Bernstein, 1993, p. 23).

This paper along with a seminal series of lectures given by Luria at the Tavistock Institute in London sparked an intense interest in the Russian Cultural Historical tradition and went on to exert a profound influence on post war developments in English in Education, the introduction of education for young people with severe and profound learning difficulties, and theories and practices designed to facilitate development and learning in socially disadvantaged groups in the United Kingdom. In November 1964 Bernstein wrote a letter to Vygotsky’s widow outlining her late husband’s influence on his developing thesis.

As you may know, many of us working in the area of speech (from the perspective of psychology as well as from the perspective of sociology) think that we owe a debt to the Russian school, especially to works based on Vygotsky’s tradition. I should say that in many respects, many of us are still trying to comprehend what he said (Bernstein, 1964, p. 1).

In a commentary on the 1971 publication of “The Psychology of Art’”, Ivanov identifies Bernstein’s influence on the dissemination of Vygotsky’s ideas in the west, despite somewhat inaccurate claims about publication and disciplinary identity.

It was Vygotsky’s (Vygotsky, 1930-1934/1978) non-dualist cultural historical conception of mind claims that intermental (social) experience shapes intramental (psychological) development that continued to influence Bernstein’s thinking. This was understood as a mediated process in which culturally produced artefacts (such as forms of talk, representations in the form of ideas and beliefs, signs and symbols) shape and are shaped by human engagement with the world (Daniels, 2008; Vygotsky, 1982/1987).

Durkheim influenced both Vygotsky and Bernstein (Atkinson, 1985). On the one hand Durkheim’s notion of collective representation allowed for the social interpretation of human cognition, on the other it failed to resolve the issue as to how the collective representation is interpreted by the individual. This is the domain so appropriately filled by the later writings of Vygotsky.

Although Vygotsky (1930-1934/1978, 1982/1987) discussed the general importance of language and schooling for psychological functioning, he failed to provide an analytical framework to analyse and describe the real social systems in which these activities occur. The analysis of the structure and function of semiotic psychological tools in specific activity contexts is not explored. The challenge is to address the demands created by this absence.

Bernstein (1996) outlined a model for understanding the construction of pedagogic discourse. In this context pedagogic discourse is a source of psychological tools or cultural artefacts. “The basic idea was to view this [pedagogic] discourse as arising out of the action of (…) a group of specialised agents operating in specialised setting in terms of the interests, often competing interests, of this setting” (p. 113).

In Engeström’s (1996) work within activity theory, which to some considerable extent has a Vygotskian root, the production of the outcome of activity is discussed but not the production and structure of cultural artefacts such as discourse. The production of discourse is not analysed in terms of the context of its production, that is the rules, community and division of labour, which regulate the activity in which subjects are positioned. It is therefore important that the discourse is seen within the culture and structures of schooling where differences in pedagogic practices, in the structuring of interactions and relationships, and the generation of different criteria of competence, will shape the ways in which children are perceived and actions are argued and justified. This is the agenda which Hasan (2005) has pursued in an approach that draws on Halliday, Vygotsky and Bernstein.

The application of Vygotsky by many social scientists (e.g. linguists, psychologists and sociologists) has been limited to relatively small scale interactional contexts often within schooling or some form of educational setting. The descriptions and the form of analysis are in some sense specific to these contexts.

In his work on schooling, Bernstein (2000) argues that pedagogic discourse is constructed by a recontextualising principle which selectively appropriates, relocates, refocuses and relates other discourses to constitute its own order. He argues that in order to understand pedagogic discourse as a social and historical construction attention must be directed to the regulation of its structure, the social relations of its production and the various modes of its recontextualising as a practice. For him symbolic tools are never neutral; intrinsic to their construction are social classifications, stratifications, distributions and modes of recontextualizing.

The language that Bernstein (2000) has developed allows researchers to take measures of institutional modality. That is to describe and position the discursive, organizational and interactional practice of the institution. His model is one that is designed to relate macro-institutional forms to micro-interactional levels and the underlying rules of communicative competence. He focuses on two levels: a structural level and an interactional level. The structural level is analysed in terms of the social division of labour it creates (e.g. the degree of specialisation, and thus strength of boundary between professional groupings) and the interactional with the form of social relation it creates (e.g. the degree of control that a manager may exert over a team member’s work plan). The social division is analysed in terms of the strength of the boundary of its divisions; that is, with respect to the degree of specialisation (e.g. how strong is the boundary between professions such as teaching and social work or one school curriculum subject and another). Bernstein (1996) refined the discussion of his distinction between instructional and regulative discourse. The former refers to the transmission of skills and their relation to each other, and the latter refers to the principles of social order, relation and identity. Regulative discourse communicates the school’s (or any institution’s) public moral practice, values beliefs and attitudes, principles of conduct, character and manner. Pedagogic discourse is modelled as one discourse created by the embedding of instructional and regulative discourse. Bernstein provides an account of cultural transmission which is avowedly sociological in its conception. In turn the psychological account that has developed in the wake of Vygotsky’s writing offers a model of aspects of the social formation of mind which is underdeveloped in Bernstein’s work.

Mediation

Discourse may mediate human action in different ways. There is visible (Bernstein, 2000) or explicit (Wertsch, 2007) mediation in which the deliberate incorporation of signs into human action is seen as a means of reorganising that action. This contrasts with invisible or implicit mediation that involves signs, especially natural language, whose primary function is in communications which are part of a pre-existing, independent stream of communicative action that becomes integrated with other forms of goaldirected behaviour (Wertsch, 2007). Invisible semiotic mediation occurs in discourse embedded in everyday ordinary activities of a social subject’s life.

As Hasan (2001, p. 8) argues, Bernstein further nuances this claim:

What Bernstein referred to as the ‘invisible’ component of communication (see Bernstein 1990: 17, figure 3.1 and discussion). The code theory relates this component to the subject’s social positioning. If we grant that “ideology is constituted through and in such positioning” (Bernstein 1990: 13), then we grant that subjects’ stance to their universe is being invoked: different orders of relevance inhere in different experiences of positioning and being positioned. This is where the nature of what one wants to say, not its absolute specifics, may be traced. Of course, linguists are right that speakers can say what they want to say, but an important question is: what is the range of meanings they freely and voluntarily mean, and why do they prioritize those meanings when the possibilities of making meanings from the point of view of the system of language are infinite? Why do they want to say what they do say? The regularities in discourse have roots that run much deeper than linguistics has cared to fathom.

This argument is strengthened through its reference to a theoretical account which provides greater descriptive and analytical purchase on the principles of regulation of the social figured world, the possibilities for social position and the voice of participants.

These challenges of studying implicit or invisible mediation have been approached from a variety of theoretical perspectives. Holland, Lachiotte, Skinner, & Cain (1998) have studied the development of identities and agency specific to historically situated, socially enacted, culturally constructed worlds in a way that may contribute to the development of an understanding of the situatedness of the development of social capital. This approach to a theory of identity in practice is grounded in the notion of a figured world in which positions are taken up constructed and resisted. The Bakhtinian concept of the space of authoring is deployed to capture an understanding of the mutual shaping of figured worlds and identities in social practice. They refer to Bourdieu (as cited in Holland et al., 1998) in their attempt to show how social position becomes disposition. They argue for the development of social position into a positional identity into disposition and the formation of what Bourdieu refers to as habitus. Bernstein is critical of habitus arguing that the internal structure of a particular habitus, the mode of its specific acquisition, which gives it its specificity, is not described. For him habitus is known by its output not its input (Bernstein, 2000).

Wertsch (1998) turned to Bakhtin’s theory of speech genres rather than habitus. A similar conceptual problem emerges with this body of work. Whilst Bakhtin’s views concerning speech genres are ‘rhetorically attractive and impressive, the approach lacks … both a developed conceptual syntax and an adequate language of description. Terms and units at both these levels in Bakhtin’s writings (1978, 1986/1986) require clarification; further, the principles that underlie the calibration of the elements of context with the generic shape of the text are underdeveloped, as is the general schema for the description of contexts for interaction (Hasan, 2005). Bernstein acknowledges the importance of Foucault’s analysis of power, knowledge and discourse as he attempts to theorise the discursive positioning of the subject. He complains that it lacks a theory of transmission, its agencies and its social base.

Identity and Agency

Hasan brings Bernstein’s concept of social positioning to the fore in her discussion of social identity. Bernstein (1990, p. 13) used this concept to refer to “the establishing of a specific relation to other subjects and to the creating of specific relationships within subjects”. He forged a link between social positioning and psychological attributes. This is the process through which Bernstein talks of the shaping of the possibilities for consciousness. The dialectical relation between discourse and subject makes it possible to think of pedagogic discourse as a semiotic means that regulates or traces the generation of subjects’ positions in discourse. We can understand the potency of pedagogic discourse in selectively producing subjects and their identities in a temporal and spatial dimension (Diaz, 2001). As Hasan (2005) argues, within the Bernsteinian thesis there exists an ineluctable relation between one’s social positioning, one’s mental dispositions and one’s relation to the distribution of labour in society. Here the emphasis on discourse is theorised not only in terms of the shaping of cognitive functions but also, as it were invisibly, in its influence on “dispositions, identities and practices”(Bernstein, 1990, p. 33).

Within Engeström’s approach to Cultural Historical Activity Theory (1999a) the subject is often discussed in terms of individuals, groups or perspectives/views. I would argue that the way in which subjects are positioned with respect to one another within an activity carries with it implications for engagement with tools and objects. It may also carry implications for the ways in which rules, the community and the division of labour regulate actions, including learning, of individuals and groups.

Holland et al. (1998) have studied the development of identities and agency specific to historically situated, socially enacted, culturally constructed worlds. They draw on Bakhtin and Vygotsky to develop a theory of identity as constantly forming and in which the person is understood as a composite “of many, often contradictory, selfunderstandings and identities (…) [which are distributed across] the material and social environment and (…) [are rarely] durable” (p. 8). Holland et al. (1998) draw on Leont’ev in the development of the concept of socially organized and reproduced figured worlds which shape and are shaped by participants and in which social position establishes possibilities for engagement. They also argue that figured worlds:

Distribute “us” not only by relating actors to landscapes of action (as personae) and spreading our senses of self across many different fields of activity, but also by giving the landscape human voice and tone (…). Cultural worlds are populated by familiar social types and even identifiable persons, not simply differentiated by some abstract division of labor. The identities we gain within figured worlds are thus specifically historical developments, grown through continued participation in the positions defined by the social organization of those world’s activity [emphasis added] (Holland et al. 1998, p. 41).

This approach to a theory of identity in practice is grounded in the notion of a figured world in which positions are taken up constructed and resisted. They argue for the development of social position into a positional identity into disposition and the formation of what Bourdieu refers to as habitus. It is here that I feel that this argument could be strengthened through reference to a theoretical account which provides greater descriptive and analytical purchase on the principles of regulation of the social figured world, the possibilities for social position and the voice of participants.

Engeström (1999b), who has tended to concentrate on the structural aspects of CHAT, offers the suggestion that the division of labour in an activity creates different positions for the participants and that the participants carry their own diverse histories with them into the activity. This echoes the earlier assertion from Leont’ev:

Activity is the minimal meaningful context for understanding individual actions… In all its varied forms, the activity of the human individual is a system set within a system of social relations… The activity of individual people thus depends on their social position [emphasis added], the conditions that fall to their lot, and an accumulation of idiosyncratic, individual factors. Human activity is not a relation between a person and a society that confronts him…in a society a person does not simply find external conditions to which he must adapt his activity, but, rather, these very social conditions bear within themselves the motives and goals of his activity, its means and modes. (Leont’ev, 1978, p. 10).

In activity the possibilities for the use of artefacts depend on the social position occupied by an individual. Sociologists and sociolinguists have produced empirical verification of this suggestion (Bernstein, 2000; Hasan, 2001; Hasan & Cloran, 1990). My suggestion is that the notion of subject within activity theory requires expansion and clarification. In many studies the term subject perspective is used which arguably infers subject position but does little to illuminate the formative processes that gave rise to this perspective.

Holland et al. (1998) also argue that multiple identities are developed within figured worlds and that these are “historical developments, grown through continued participation in the positions defined by the social organization of those worlds’ activity” (p. 41). This body of work represents a significant development in our understanding of the concept of the subject in activity theory.

Conclusion

The language that Bernstein has developed allows researchers to develop measures of school modality. That is, to describe and position the discursive, organizational and interactional practice of the institution. He also noted the need for the extension of this work in his discussion of the importance of Vygotsky’s work for research in education.

“His theoretical perspective also makes demands for a new methodology, for the development of languages of description which will facilitate a multilevel understanding of pedagogic discourse, the varieties of its practice and contexts of its realization and production” (Bernstein, 1993, p. 23).

This approach to modelling the structural relations of power and control in institutional settings taken together with a theory of cultural–historical artefacts that invisibly or implicitly mediate the relations of participants in practices forms a powerful alliance. It carries with it the possibility of rethinking notions of agency and reconceptualising subject position in terms of the relations between possibilities afforded within the division of labour and the rules that constrain possibility and direct and deflect the attention of participants.

It accounts for the ways in which the practices of a community, such as school and the family are structured by their institutional context and that social structures impact on the interactions between the participants and the cultural tools. Thus, it is not just a matter of the structuring of interactions between the participants and other cultural tools; rather it is that the institutional structures themselves are cultural products that serve as mediators in their own right. In this sense, they are the message, that is a fundamental factor of education. As Hasan (2001) argues, when we talk, we enter the flow of communication in a stream of both history and the future. There is therefore a need to analyze and codify the mediational structures as they deflect and direct the attention of participants and as they are shaped through interactions which they also shape. In this sense, combining the intellectual legacies of Bernstein and Vygotsky permits the development of cultural historical analysis of the invisible or implicit mediational properties of institutional structures which themselves are transformed through the actions of those whose interactions are influenced by them. This move would serve to both expand the gaze of post Vygotskian theory and at the same time bring sociologies of cultural transmission into a framework in which institutional structures are analyzed as historical products which themselves are subject to dynamic transformation and change as people act within and on them.

References

Atkinson, P. (1985). Language, structure, and reproduction: An introduction to the sociology of Basil Bernstein. London, UK: Methuen.

Bakhtin, M.M. (1978). The problem of the text (An essay in the philosophical analysis). Soviet Studies in Literature, 14(1), 3-33. doi: 10.2753/RSL1061-1975140163

Bakhtin, M.M. (1986). The problem of speech genres (V.W. McGee, Trans.). In C. Emerson & M. Holquist (Eds.), Speech genres and other late essays (Series 8, pp. 60-102). Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press. (Reprinted from Éstetika slogesnovo tvorchestva, pp. 192-198, by M.M. Bakhtin, Ed., 1986, Moscow, Russia: Iskusstvo).

Bernstein, B. (1964, November, 27). Letter to Vygotsky’s Widow, Mimeo.

Bernstein, B. (1990). The structuring of pedagogic discourse: class, codes and control (Vol. 4). London, UK: Routledge.

Bernstein, B. (1993). Foreword. In H. Daniels (Ed.), Charting the Agenda: educational activity after Vygotsky (pp. 13-23). London, UK: Routledge.

Bernstein, B. (1996). Pedagogy symbolic control and identity: Theory, research, criticism. London, UK: Falmer Press.

Bernstein, B. (2000). Pedagogy symbolic control and identity: Theory, research, criticism (Rev. ed.). London: Falmer Press.

Daniels, H. (2001). Vygotsky and Pedagogy. London, UK: Routledge.

Daniels, H. (2006). Analysing institutional effects in activity theory: First steps in the development of a language of description. Outlines: Critical Social Studies, 8(2), 43-58. Retrieved from http://ojs.statsbiblioteket.dk/index.php/outlines/article/view/2091

Daniels, H. (2008). Vygotsky and research. London, UK: Routledge

Daniels, H. (2010). The mutual shaping of human action and institutional settings: a study of the transformation of children’s services and professional work. The British Journal of Sociology of Education, 31(4), 377-393. doi: 10.1080/01425692.2010.484916

Davydov, V.V. (1995). The influence of L. S. Vygotsky on education theory, research, and practice. Educational Researcher, 24(3), 12-21. doi: 10.3102/0013189X024003012

Diaz, M (2001). The importance of Basil Bernstein. In S. Power, P. Aggleton, J. Brannen, A. Brown, L. Chisholm, L., & J. Mace (Eds.), A tribute to Basil Bernstein 1924-2000 (pp. 114-116). London, UK: Institute of Education, University of London.

Down, CM. (2003). Situated learning: Perceptions of training practitioners of the transfer of competence across workplace contexts (Doctoral dissertation, Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology, Australia). Retrieved from https://researchbank.rmit.edu.au/eserv/ rmit:6311/Down_PartA.pdf

Engeström, Y. (1987). Learning by expanding: An activity-theoretical approach to developmental research. Helsinki, Finland: Orienta-Konsultit Oy Publisher.

Engeström, Y. (1996). Development as breaking away and opening up: A challenge to Vygotsky and Piaget. Swiss Journal of Psychology, 55(2), 126–132. Retrieved from http://lchc.ucsd.edu/mca/Paper/Engestrom/Engestrom.html

Engeström, Y. (1999a). Activity theory and individual and social transformation. In Y. Engeström, R. Miettinen, & R.-L. Punamäki (Eds.), Perspectives on activity theory (pp. 19-38). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Engeström, Y. (1999b). Innovative learning in work teams: Analyzing the cycles of knowledge creation in practice. In Y. Engeström, R. Miettinen, & R.-L. Punamäki (Eds.), Perspectives on activity theory (pp. 377-404). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Engeström, Y. & Sannino, A. (2010). Studies of expansive learning: Foundations, findings and future challenges. Educational Research Review, 5(1), 1-24. doi:10.1016/j. edurev.2009.12.002.

Fitz, J. (2007). [Review of the book Knowledge, power and educational reform, applying the sociology of Basil Bernstein, by R. Moore, M. Arnot, J. Beck, & H. Daniels]. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 28(2), 273-279. Retrieved from http://www.jstor. org/stable/30036202

Hasan, R. (2001). Understanding talk: Directions from Bernstein’s sociology. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 4(1), 5-9. doi: 10.1080/13645570010028549

Hasan, R. (2005). Semiotic mediation, language and society: Three exotripic theories – Vygotsky, Halliday and Bernstein. In J. Webster (Ed.), Language, society and consciousness: Ruqaiya Hasan (Vol. 1, pp. 55-80). London, UK: Equinox.

Hasan, R. & Cloran, C. (1990). A sociolinguistic study of everyday talk between mothers and children. In M.A.K. Halliday, J. Gibbons, & H. Nicholas (Eds.), Learning keeping and using language (Vol. 1, pp. 104-131). Amsterdam, Netherlands: John Benjamins.

Holland, D., Lachiotte, L., Skinner, D., & Cain, C. (1998). Identity and agency in cultural worlds. Cambridge, Massachusets, USA.: Harvard University Press. Ivanov, V.V. (1971). Commentary. In L.S. Vigotsky (Ed.), The psychology of art (pp. 265- 295). Cambridge, Massachusetts. USA: MIT Press.

Leont’ev, A. N. (1978) Activity, consciousness and personality. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, USA: Prentice Hall.

Van der Veer, R. (1996). The concept of culture in Vygotsky’s thinking. Culture Psychology, 2(3), 247-263. doi: 10.1177/1354067X9600200302

Vygotsky, L.S. (1978) Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes (M. Cole, V. John-Steiner, S. Scribner, & E. Souberman, Trans.). Cambridge, Massachusets, USA: Harvard University Press. (Reprinted from Разум в обществе, by L.S. Vygotsky, Ed., [ca. 1930-1934], Russia).

Vygotsky, L.S. (1981). The genesis of higher mental functions (J.V. Wertsch, Trans.). In J.V. Wertsch (Ed.), The concept of activity in soviet psychology (pp. 144-188). Armonk: M E Sharp. (Reprinted from Razvitie vysshikh psikhicheskikh funktsii, by L.S. Vigotsky, L.S., Ed., 1960, Moscow, Russia).

Vygotsky, L.S. (1987). Thinking and speech (N. Minick, Trans.). In R.W. Rieber, A.S. Carton, & N. Minick (Eds.), The collected works of L.S. Vygotsky: Problems of general psychology (Vol. 1). New York, USA: Plenum Press. (Reprinted from Sobranie sochinenii, by L.S. Vygotsky, Ed., 1982, Moscow, Russia: Aksenov).

Wertsch, J.V. (1998). [Review of the book Pedagogy, symbolic control and identity: Theory, research, critique, by B. Bernstein]. Language in Society, 27(2), 257-259. doi: 10.1017/ S0047404500019904

Wertsch, J.V. (2007). Mediation. In H. Daniels, M. Cole, & J.V. Wertsch (Eds.), The Cambridge Companion to Vygotsky (pp. 178-193). New York, USA: Cambridge University Press.

Fuente del Artículo:

http://revistas.um.es/rie/article/view/252801/195001

Users Today : 17

Users Today : 17 Total Users : 35460370

Total Users : 35460370 Views Today : 24

Views Today : 24 Total views : 3419124

Total views : 3419124