Bagdag / www.lainformacion.com / 2 de Noviembre de 2016

El rico patrimonio iraquí, ya severamente dañado por la campaña de vandalismo y destrucción del grupo Estado Islámico (EI), corre el riesgo de sufrir nuevas destrucciones en la batalla por reconquistar la ciudad de Mosul, en manos de los yihadistas.

En 2014, después de apoderarse de Mosul, la segunda ciudad de Irak, el EI destrozó el museo, donde se encontraban inestimables objetos de las épocas asiria y helenística.

El grupo extremista también atacó las ciudades antiguas de Hatra y Nimrod, no lejos de Mosul, y mostró su destrucción en videos.

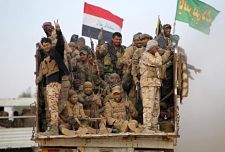

Las fuerzas iraquiés están estrechando el cerco sobre Mosul, último gran bastión del EI en el país, pero los yihadistas permanecen dentro o alrededor de sitios históricos.

«Según nuestras informaciones, (el EI) está presente en los sitios arqueológicos», declaró Ahmed al Asadi, portavoz de las Hashd al Shaabi, una coalición de milicias chiitas apoyadas por Irán.

Las Hashd lanzaron una operación el sábado que podría conllevar combates contra el EI en regiones donde se hallan varios de los sitios arqueológicos iraquíes más conocidos, como Hatra y Nimrod.

Hatra, una antigua ciudad fortificada de más de 2.000 años, se encontraba bastante bien conservada. En ella había impresionantes templos, donde la arquitectura griega y romana se mezclaba con elementos de origen oriental.

En Nimrod, seguían habiendo bajorrelieves y colosales «lamassu» (toros alados con rostro humano), aunque la mayoría de los objetos procedentes de esta ciudad asiria ya están expuestos desde hace tiempo en museos de Mosul, Bagdad, París o Londres.

«Creemos que (el EI) intenta atraer a las fuerzas (iraquíes) hacia estos sitios, para destrozarlos todavía más», dijo Asadi.

El EI ya había instalado un campamento de entrenamiento en la ciudad antigua de Hatra, inscrita en el patrimonio mundial de la Humanidad por la Unesco. Y sigue albergando a combatientes, afirma Ali Saleh Madhi, un responsable iraquí de la zona.

En Nimrod, el EI había colocado explosivos en los monumentos e hizo estallar el sitio. Los extremistas siguen sin embargo en los alrededores, según Ahmed al Jubori, el administrador de la zona.

Cuando se lanzó la operación para reconquistar Mosul el 17 de octubre, la Unesco había pedido a «todos los actores implicados en esta acción militar proteger el patrimonio cultural, no utilizarlo con fines militares y evitar tomar los sitios y monumentos culturales como objetivos».

La Unesco y el ministerio de Cultura iraquí distribuyeron a las fuerzas antiyihadistas listas con los sitios culturales, así como sus coordenadas GPS. En la lista de la Unesco, 15 de los 80 nombres aparecían con la apelación «sitio del patrimonio de la Humanidad con una significación cultural extrema».

Según el viceministro de Cultura, Qais Rashid, el repertorio del ministerio contiene las coordenadas de los sitios donde los combatientes del EI están presentes. Los yihadistas colocan «armas y a veces entrenan a sus combatientes en los sitios arqueológicos», precisó.

Desde su ocupación de varios territorios iraquíes en 2014, los yihadistas lanzaron una campaña de destrucción, que ellos justifican por razones religiosas, para eliminar a los «ídolos».

En realidad, los ataques contra el patrimonio cultural tienen objetivos propagandísticos, y la venta de objetos en el mercado negro sirve también para financiar al grupo.

En febrero, el EI publicó un video donde se veían a combatientes armados con mazos y taladros arrasando el museo de Mosul. Estas imágenes provocaron una ola de indignación.

La Unesco calificó «la demolición del museo de Mosul y la destrucción de los vestigios arqueológicos de Nínive (…) como uno de los ataques más bárbaros contra el patrimonio de la Humanidad».

«Estos crímenes no pueden quedar impunes», advirtió la institución.

Fuente:http://www.lainformacion.com/politica/defensa/batalla-Mosul-nuevamente-peligro-patrimonio_0_967704271.html

Users Today : 66

Users Today : 66 Total Users : 35404544

Total Users : 35404544 Views Today : 75

Views Today : 75 Total views : 3334115

Total views : 3334115