Inclusive education is a form of teaching that uses physical accessibility, individual education plans, toys and teaching aids to support children with disabilities. Find out how it’s changing the shape of one boy’s future in Rwanda.

Africa/Rwanda/PrensaUNICEF/By Veronica Houser

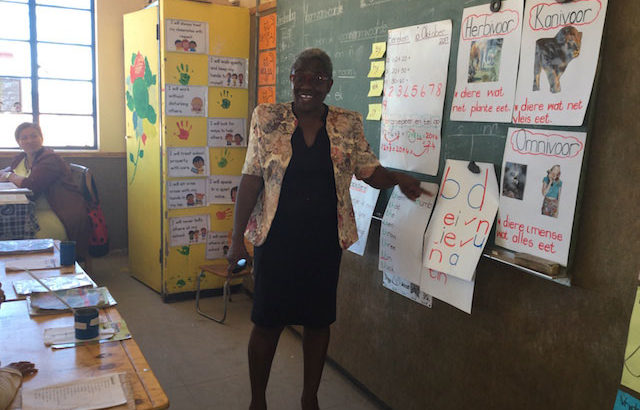

Resumen: Cuando Olivier, de 11 años, era apenas un bebé, su padre se preocupó cuando notó que su hijo pequeño se estaba desarrollando a un ritmo más lento que sus seis hermanos y hermanas. «Ni siquiera podía orinar», dice Innocent Ntawimenya, el padre de Olivier. «Me pregunté, ¿podría incluso crecer?»Cuando era un niño pequeño, Olivier tenía habilidades motoras débiles y no podía sostener ni siquiera objetos pequeños. A pesar de que estaba inscrito en la escuela de su ciudad en el sur de Ruanda, no se relacionó con otros niños y tenía muy pocos amigos. «Los otros niños solían llamar a Olivier nombres abusivos. Le dijeron que era estúpido «, dice Inocente con voz temblorosa. Para evitar la intimidación, Inocencio y su esposa comenzaron a acompañar a Olivier a donde quiera que fuera. Un maestro ayuda a los estudiantes en uno de los salones de Ruhango Catholique. El programa de educación inclusiva brinda capacitación a los maestros para que puedan incorporar herramientas para niños con discapacidades en sus lecciones diarias. Los maestros de Ruhango Catholique también están capacitados en la enseñanza «centrada en el alumno», donde los niños aprenden a través de actividades prácticas y trabajo en grupo, y mediante el autodescubrimiento. Esta forma de enseñanza permite a los niños como Olivier aprender de y con otros niños, así como a sus maestros. En la clase de hoy, los niños sostienen dos dedos con el pulgar entre ellos para indicar la letra «K» en el alfabeto de la Lengua de Señas inglesa. Mientras el maestro de Olivier se mueve por la sala haciendo preguntas, los estudiantes saltan emocionados, con las manos en el aire, gritando: «¡Maestro, por favor, a mí!»

When 11-year-old Olivier was a just a baby, his father became concerned when he noticed his young son was developing at a slower pace than his six brothers and sisters.

“He was not even able to urinate,” says Innocent Ntawimenya, Olivier’s father. “I asked myself, would he even be able to grow?”

As a young child, Olivier had weak motor skills and couldn’t hold even small objects. Although he was enrolled in school in their town in southern Rwanda, he didn’t engage with other children and had very few friends.

“The other children used to call Olivier abusive names. They told him he was stupid,” says Innocent with a trembling voice. To avoid the bullying, Innocent and his wife began to accompany Olivier wherever he went.

Innocent knew that Olivier needed a change. He and his wife decided to enrol him at G.S. Ruhango Catholique, a UNICEF-supported school that promotes inclusive education for children with disabilities. The school has been rehabilitated with ramps, wider pathways and door frames, and disability-friendly toilets. Students with learning impairments are taught in an integrated classroom alongside other students.Learning from each other

Teachers at Ruhango Catholique are also trained in ‘student-centred’ teaching, where children learn through hands-on activities and group work, and through self-discovery. This way of teaching empowers children like Olivier to learn from and with other children, as well as their teachers.

In today’s class, children hold up two fingers with their thumb between to indicate the letter ‘K’ in the English Sign Language alphabet. As Olivier’s teacher moves around the room asking questions, students jump excitedly, their hands in the air, shouting, “Teacher, please, me!”

Inclusive schools also involve parents through resource rooms, where they learn to make learning and teaching aids from locally available materials.Getting parents involved

“I like visiting my son’s school,” Innocent says. “I like spending time in the resource room with other parents, making things to help Olivier and other students learn.” He uses the materials to reinforce Oliver’s education at home, so he can continue to develop outside the classroom.

Now in his second year of primary school, Olivier has shown vast improvement. Innocent smiles proudly, reporting that Olivier can now count to 1,000, and his motor skills have improved so much that he can even lift a 5-liter jerry can.

“He loves sports, especially football,” says Innocent. “He is now willing to play with others, and the other children no longer treat him badly.” He beams as Olivier comes to join him after his class, sitting on his lap while he embraces him.

Innocent looks down at his hands, speaking slowly and deliberately.

“I can see that Olivier will continue to progress throughout his life, and I am so grateful. I never thought such improvement could be achieved so quickly.”

The 2015 Study on Children with Disabilities and their Right to Education: Republic of Rwanda noted that there is no incentive for schools to accept children with disabilities, and there is a lack of awareness about the learning barriers they face. UNICEF Rwanda supports the Government to implement the national Inclusive Education Policy in all 30 districts, and to address sociocultural barriers which impede educational access, learning and completion for children with disabilities.

Fuente: https://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/rwanda_102776.html

Users Today : 32

Users Today : 32 Total Users : 35404510

Total Users : 35404510 Views Today : 34

Views Today : 34 Total views : 3334074

Total views : 3334074