Labornotes/ Jane Slaughter

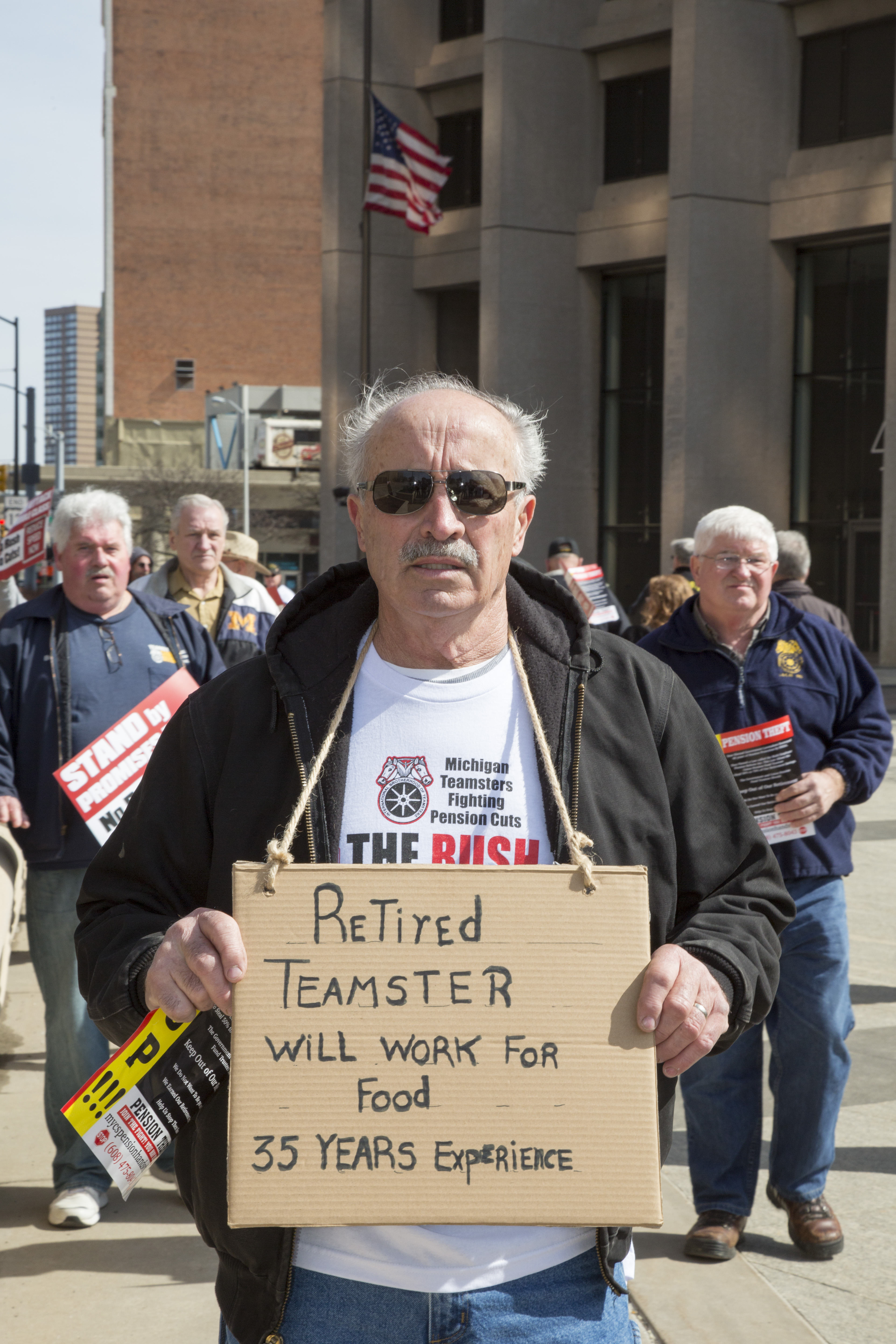

As they picketed in downtown Detroit Friday over cuts to their pensions, some retired Teamsters were quick to point out that they were not the worst off. “I’ve still got my health and a part-time job that keeps me busy,” said Jim Carothers.

Carothers is facing a 60 percent cut to the pension he earned over 34 years as a carhauler, driving finished autos from the assembly line to dealerships. On July 1 his benefit would fall from $40,000 a year to $16,000, under a proposal from the Central States Pension Fund. But “I’m one of the lucky ones,” he says.

Carothers cites fellow Teamsters who will lose their homes, and a couple who are caring for their 39-year-old severely disabled daughter. “What’s going to happen to those folks?” he asks.

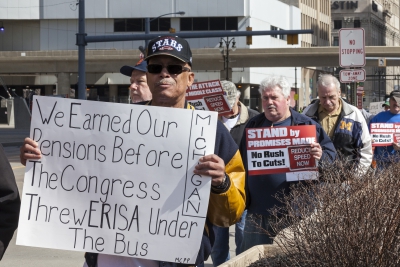

The Detroit picket was one of five this weekend called by angry Teamster retirees under the rubric of “March Madness,” with actions also held in Kansas City, St. Paul, Columbus, and Dunn, North Carolina. They are part of awave of organized wrath over the Central States Fund’s plan to slash existing retirees’ pensions by 50 to 60 percent.

“We haven’t seen this many people coming out to rallies, ever,” said Pete Landon of Teamsters for a Democratic Union, which is helping the organizing. Eight hundred filled a hall last month in Detroit. Columbus and Kansas City drew 500 and 1,200, Minneapolis 750, Milwaukee 300, Cincinnati 200, Houston 300. Retirees have formed “Committees to Protect Pensions” in 20 cities, with Facebook pages set up in a dozen more.

410,000 Livelihoods at Stake

They plan to descend on Washington, D.C., April 14 to support the Keep Our Pension Promises Act (KOPPA) and to ask the Treasury Department to reject the Central States proposal, which will hurt 410,000 Teamsters in 25 states from Florida to Minnesota.

In February, Rita Lewis, widow of a Cincinnati retiree who was a leader of both the pension movement and the Teamster reform movement, asked the Senate Finance Committee for bipartisan Congressional action to help the retirees. The movement has generated two bills in Congress.

KOPPA, introduced by Senator Bernie Sanders and Congresswoman Marcy Kaptur of Ohio, would solve the Central States’ underfunding problem by providing backstop money for the Central States retirees whose companies ran away or went bankrupt. The money would come from closing certain corporate tax loopholes.

A second bill, introduced by Republican Senator Rob Portman of Ohio, would at least give retirees a fair vote on the issue, allowing them to say no and work for a better solution (as it stands, their vote can be vetoed by the Treasury Department). Many Congressional reps and senators have signed on to the retirees’ call for Treasury to reject the Central States plan as presented.

“The retirees have learned how to be citizen lobbyists, backed by a movement,” said Landon. They have been aided by thePension Rights Center, which has provided both organizing savvy and technical help on alternative fixes to the problem.

It Takes Your Dignity

Terry Elswick, 57, spent 33 years as a claims clerk for a freight company. Now she walks with a cane. “It broke my heart to retire,” she says. She could not go back to work after a broken back, and says the Fund encouraged her to take early retirement.

“Now they treat us like we’re shamming the Fund,” she says. “It takes your dignity.”

Fund trustees—half from management, half from the Teamsters—want to cut her benefit from $2,850 a month to $1,400. She doesn’t know whether she and her husband, who is facing a similar cut, will be able to keep their home. “We’re used to helping our kids,” Elswick said. “We won’t be able to do that anymore.”

Her husband points out that the Fund’s resources plummeted while it was supposedly under the watchful eye of the federal government. A 1982 consent decree, designed to rid the Fund of corruption, turned over management of much of its assets to Wall Street firms such as Goldman Sachs. These firms collected more than a quarter-billion dollars in fees just in 2009-2013.

For a while, the Fund was flush—so flush that the IRS ordered the trustees to either take in less money or pay out more. They started sending retirees a 13th check each year, and later instituted “30-and-Out” and then “25-and-Out.”

Retirees made plans accordingly, not knowing that their union president and UPS would impoverish the Fund (see sidebar). “I won’t be making any major purchases, that’s for sure,” said Billy Scott, 68, of Detroit. “You just hope to have enough to cover your medications and your doctor’s bill co-pays.”

Scott was in on national negotiations with the carhaul companies for 12 years. “You tell the members, ‘everyone wants a raise, but you need money for the pension contribution,’” he explained. “You ask people to give up a wage increase to stabilize their pension.”

Snowball Is Rolling

Scott is concerned that “if we fail, it will start a snowball. There are 10 million people in multi-employer funds, that this could happen to next. And who’s to say they won’t pass a new law for single-employer funds, too? There are lots of pension funds that are in trouble.”

The Upstate New York Pension Plan, covering 35,000 Teamsters, has just announced its own first steps to slash benefits, as have a small Teamster plan in New Jersey and an Ironworkers fund based in Cleveland.

The Boston College Center for Retirement Research lists 100 troubled funds that could apply to cut members’ pensions. A United Mine Workers fund, for example, has 115,120 participants, almost all of them retired; fewer than 12,000 are still working and thus paying into the fund.

At a recent hearing, Senator Ron Wyden of Oregon condemned the 2014 law and called the state of multi-employer pensions a “public policy emergency.”

Wayne and Jeni Ottney drove from Eaton Rapids, Michigan, to join the line. Wayne said he retired when his freight company started laying off, so that a younger man could have his place. Now, facing a 50 percent cut at the age of 65, “they try to tell me I can go back to the job.

“I always worked afternoons, for 35 years,” Wayne said. “I missed my children growing up—for a pension.”

Now he worries that one of those children also has a target on his back. His son is a union Sheetmetal worker whose pension is also in a multi-employer fund.

One auto worker joined the Teamster picketers in Detroit: Ford employee Jason Krzysiak. His Teamster father is facing draconian cuts. “You have conversations with your little ones,” he said, “what your word means, what a promise means. And then they see the struggles grandpa’s going through…”

As of last fall’s contract, Krzysiak said, his Ford pension was secure. He’s a 20-year employee. But he pointed out that Big 3 workers hired since 2007 don’t have pensions. “If this is the way the UAW is going with the new-hires, what security is there for me as a legacy employee?” he asked. “A generation ago, it seemed more secure.”

Why These Cuts?

In 2008 President James Hoffa allowed United Parcel Service, by far the largest employer of Teamsters, to pull out of the Central States Pension Fund, the nation’s second-largest multi-employer pension plan.

If 45,000 UPS workers in the Central States area were still members, the Fund’s annual income would be more than double what it is now.

The Fund lost $8.8 billion in the stock market crash of 2008. Central States projects that it has only $18 billion available to pay the $34 billion it owes to current and future retirees. Ten years from now, the Fund director claims, it could become insolvent, with retirees dumped into the severely underfunded Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation (PBGC).

In December 2014 Congress passed the Multiemployer Pension Reform Act (MPRA) after heavy lobbying from Central States, with no public hearings and no debate. Neither the House nor the Senate voted on the bill directly; it was attached to the omnibus budget bill, literally in the middle of the night.

The new law allows multi-employer funds to cut benefits to existing retirees, which until then had been illegal under ERISA.

The PBGC, the public agency set up as a backstop for troubled pension funds, does not have enough money to deal with a Central States default. PBGC is not backed by federal money but exists solely on the relatively small required contributions from employers and plans.

Users Today : 17

Users Today : 17 Total Users : 35460226

Total Users : 35460226 Views Today : 22

Views Today : 22 Total views : 3418917

Total views : 3418917