Un retuit, reblog, “me gusta” entre otros vienen como bálsamo para la generación de la gratificación inmediata donde un contenido más, sea libre o no, es un elemento para la colección.

Por Luis Fernando Medina*

En el siguiente texto busco explorar de una manera muy intuitiva y breve, y basado en mi experiencia como académico, investigador y activista, algunas consideraciones críticas de los modelos abiertos y la llamada cultura libre. Indudablemente, como ocurre con las iniciativas de este talante, el propósito no será dar una respuesta única y absoluta, sino tal vez procurar lanzar algunas preguntas esperando que estas sean las adecuadas. Sin embargo, tampoco es mi intención acudir a ésta fórmula como pretexto para eludir conclusiones, por lo cual procuraré esbozar alguna recomendación útil, en la medida en que la retórica escapista y relativista de nuestros tiempos lo permita. Para lograr el objetivo, quiero presentar dos componentes que se me hacen claves en la cultura libre y son la cultura del software y la fanática. Luego, a partir de una enunciación de algunos puntos problemáticos que observo en la cultura libre, mostraré cómo la cultura libre se ha acercado más al paradigma del software y qué consecuencias trae eso. Finalmente mencionando lo que considero algunas inexactitudes en el discurso imperante de la cultura libre avanzaré al plácido campo de la especulación con, espero, algún fruto minúsculo pero valioso.

Quiero iniciar con una anécdota para ilustrar quizá una contradicción que creo es común. El año pasado participé, en Cali, en la mesa de cultura libre del evento ComunLAB, donde se encontraban varios artistas, activistas, comunicadores, entre otros. Recuerdo que en la discusión, uno de los asistentes con bastante trayectoria en el tema de arte y lo “libre” dijo algo así como que la única manera en que concebía compartir –la única manera verdaderamente libre- era el dominio público. Curiosamente y de manera casi inmediata, otro de los asistentes se levantó y manifestó, con la firmeza de quien no domina un tema por lo que no tiene nada que perder, que no estaba de acuerdo, porque él quería poder cobrar por sus cosas. Esto alborotó un poco al auditorio, pero es mi percepción que las fuerzas se inclinaban más por la segunda intervención. ¿Qué me recordó esto?

En primer lugar, los dogmatismos que siempre han aquejado a la comunidad del software libre. Por otro lado, que el discurso de la ética hacker – el cual comparto y defiendo – a veces, sacado fuera de contexto, puede llevar a contradecir el sentido común. Y finalmente y de manera categórica; que el dinero, desestimado en ocasiones bajo el discurso de las utopías digitales, es un factor inevitable en una sociedad capitalista.

A partir de esta anécdota puede recordarse la enorme influencia de la cultura del software en la cultura libre. Indudablemente esto no es accidental, si se sigue la línea que observa que las prácticas de compartir código estuvieron siempre vinculadas con el desarrollo de software, desde los inicios de la computación y décadas antes de la invención misma del término software libre. Algo similar puede decirse de los orígenes de Internet. De manera tragicómica la tendencia fue subvertida por el software comercial el cual surgió – revolución traicionada – de las postrimerías del sueño hippie digitalizado en lo que es conocido como la filosofía californiana: computadores para liberar pero millones en la bolsa. La conexión con el software libre puede notarse también con la misma enunciación de licencias como creative commons, las cuales recuerdan directamente las libertades del software libre. Esto corresponde, como ha sido notado decenas de veces, al intento de transportar un modelo que funciona en el software, a la producción cultural con resultados más bien mixtos.

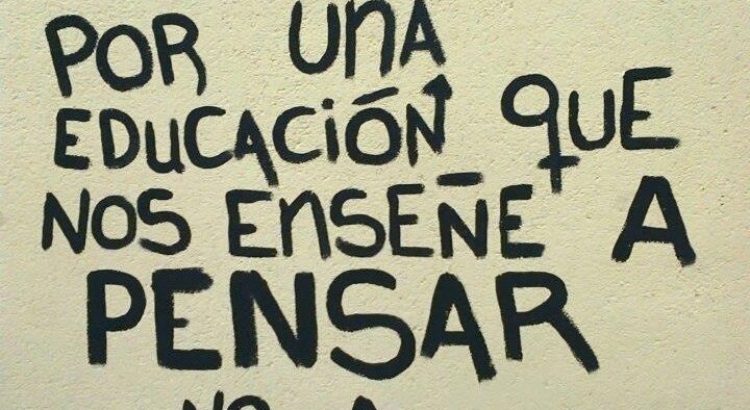

De otro lado, cabe recordar que en entornos no mediados por el software, la cultura fanática es un referente de las redes de intercambio y de formas de creación en circuitos periféricos. Dejando de lado, por no caer en la disgresión, las conocidas vanguardias artísticas que experimentaron con formas de creación y distribución, la cultura fanática que florecía alrededor de contenidos culturales, se constituía en sí misma en generación de artefactos culturales. Los fanzines, de tradición de ciencia ficción pero de explosión masiva por el fenómeno del punk y la fotocopiadora, el graffiti y sus propuestas artísticas autogestionadas (al menos en sus orígenes) o el recientemente cincuentón benemérito formato del casete, el cual ayudó a crear toda una red de distribución e intercambio para fanáticos y creadores, constituyen ejemplos paradigmáticos.

Es evidente que el compartir no está exclusivamente ligado a las tecnologías digitales y específicamente a la cultura del software ¿por qué entonces esta comparación? Más allá del breve relato histórico considero que si bien la cultura libre está también muy emparentada con la cultura fanática, es su ADN de la época digital la que la lanza al terreno donde confiar en el determinismo tecnológico puede ser un error. El software cuenta con una dualidad: puede ser compartido pero a la vez es un medio para compartir, lo cual genera algo de ruido en el momento de trasponer su paradigma hacia la cultura libre. Esto mezclado con algunos discursos absolutistas de las tecnoutopías digitales arrojan sombras sobre el rumbo del movimiento. Siguiendo con la comparación con la cultura del software libre, éste último lleva 20 años intentando encontrar un modelo de negocio efectivo, el cuál se ha dado en solo unos pocos casos. ¿Podría ocurrir lo mismo con la cultura libre y los licenciamientos abiertos? A continuación menciono aspectos que son utilizados como sustento de la cultura libre y que creo prudente desmitificar:

Lo digital es una economía de la abundancia. Esto es cierto y sirve para explicar que el costo de copiar algo es mínimo. Sin embargo, al parecer, la abundancia de bienes culturales digitales circulando puede tener doble filo. He oído a muchos artistas quejarse en voz baja (hacerlo en público sería el suicidio) de que su video, producto de mucho trabajo, palidezca en visitas en Internet, comparado con, por decir algo, el gorila revolcándose en sus heces. Que no se me malentienda, no se puede volver a los tiempos de acceso privilegiado a los medios, más la abundancia de bienes culturales circulando podría también llevar a una “inflación digital” donde el valor real de cada creación disminuye porque hay mucho de donde escoger, o simplemente la intoxicación de información es tal, que debe acudirse a agregadores, editores, curadores, con lo cual la celebrada horizontalidad del sistema sería un espejismo. Aunque estas inquietudes han sido abordadas por discursos como el de la “cola larga” y los mercados de nicho, aún los casos fehacientes de un modelo de negocio son esquivos, por lo menos a mi memoria. La más bien reciente tendencia de empezar a utilizar licencias de creative commons de “atribución” y “compartir igual” ignorando el antes casi que obvio “no comercial” implica ignorar también, de alguna manera, que los grandes medios no iban a caer como aves de rapiña sobre los contenidos abiertos y que algo estaba fallando en la generación de riqueza a partir de este modelo.

Para finalizar quiero señalar que, en ocasiones, la misma abundancia parece vencer la utopía del creador/consumidor por una cultura del capitalismo simbólico más puro e inmediato: no se trata de qué tanta información se digiera y analice si no cuánta se acumule y se le haga saber a los otros que se tiene. Un retuit, reblog, “me gusta” entre otros vienen como bálsamo para la generación de la gratificación inmediata donde un contenido más, sea libre o no, es un elemento para la colección. La misma configuración de los ISP donde la velocidad de descarga supera la de carga, o la insistencia de algunos activistas a las descargas libres más que a la educación en medios para crear, acercan a la red a ese televisor de 1000 canales de donde es difícil escoger.

¿Qué hacer? Exactamente no sé, pero considero que mientras encontramos la interfaz más adecuada para una coordinación cada vez mejor de la cultura libre dentro de un modelo capitalista, podemos reivindicar la figura del artesano digital, que se toma el tiempo en generar sus contenidos, que es un fanático que lo hace por amor al arte, dispuesto al intercambio, al trueque y los bancos de tiempo como alternativas de generación de riqueza. Así, y reinvindicando otra metáfora del software libre, aspiraremos más al pequeño bazar donde se armen pequeños círculos de creadores, y no al gran mercado donde la máscara más admirada es la del webbot cultural.

*Luis Fernando Medina Cardona, es Profesor Asociado de la Universidad Nacional de Colombia y miembro del colectivo Trueque Digital. http://about.me/luscus9

Fuente: https://www.digitalrightslac.net/es/cultura-de-webbots-o-artesanos-reflexiones-criticas-sobre-la-cultura-libre/

Users Today : 4

Users Today : 4 Total Users : 35461943

Total Users : 35461943 Views Today : 4

Views Today : 4 Total views : 3422745

Total views : 3422745