Por: Tom Westcott/middleeasteye.net/02-05-2018

Teachers in north Iraq struggle with class sizes of 100, few texts and no electricity – and no one has helped them get back on their feet

SINJAR, Iraq – Children pour out of overcrowded classrooms with shattered windows, running out onto Sinjar’s decimated streets in a cacophony of happy shouts and screams. Behind them, weary volunteer teachers head towards the sparsely furnished staff room for their daily meeting with headmaster Alias Nimr Azdo.

Most classes have over 100 pupils, who cram into classrooms sitting four to a desk

«This is the only functioning school in the whole of Sinjar and we run two shifts – morning and afternoon – to try and provide access to education for everyone here,» he told Middle East Eye. «But we are running this school with almost nothing.»

Even with all the classrooms in use during both shifts, Sinjar Mixed School is much too small for the number of pupils, who currently number more than 1,300, including 75 Muslim Shia children.

Most classes have over 100 pupils, who cram into classrooms sitting four to a desk. With insufficient teachers or space to cater for different age groups, they often have an unusual mix of ages and abilities.

But while Sinjar’s other former schools lie in ruins, either destroyed by the Islamic State (IS), which occupied much of Sinjar for a year and a half, or damaged by fighting and air strikes during the battle for liberation, there is no imminent solution to ease overcrowding.

And as word spreads that the school has reopened, it continues to attract more children, both new returnees and from Sinjar’s many outlying villages.

After four years of living as internally displaced people (IDPs), often without access to proper schooling, most families are keen for their children to try and catch up, although teachers say more than 1,000 children in nearby villages are still unable to reach the school because of transport difficulties.

Few books or pens

«We are trying to follow the official Iraqi curriculum, which is the same one as is taught in Baghdad schools, and we only teach in Arabic, even though most of the teachers don’t even speak perfect Arabic themselves, but we only have a few textbooks, so there are huge gaps in the curriculum we are able to teach,» said Azdo.

No funding or practical support, not even the textbooks which are compulsory across Iraq, have been sent to Sinjar by either the Iraqi government or the Nineweh Local Council, under whose jurisdiction Sinjar falls, he said.

We have received nothing, not even one single pen from the department of education

– Khairo K Wahb, teacher

Since the area was liberated from IS in late 2015, no representative from the Ministry of Education has even visited the town, although Azdo insisted that the terrible situation faced by the school has been made clear through multiple and regular phone calls to the ministry.

IS militants stripped the premises of all its furnishings and Azdo first opened the school using empty cardboard boxes as furniture before members of the local Hashd al-Shaabi (Popular Mobilisation) forces managed to procure desks from elsewhere.

«We have received nothing, not even one single pen from the department of education,» said qualified teacher Khairo K Wahb, shaking his head.

Two children walk home after school, past the ruins of Sinjar Old Town (MEE/Tom Westcott)

Two children walk home after school, past the ruins of Sinjar Old Town (MEE/Tom Westcott)When the school first opened last October, it tried to operate a system where parents paid 5,000 dinars ($4) per month towards schooling costs. But with most of Sinjar’s residents living below the poverty line and unable even to spare one dinar, this was abandoned.

As pupils across Iraq prepare for their end of term exams, already overwhelmed volunteer teachers have clubbed together and bought a computer and printer with their own money, to enable Sinjar’s pupils to take the national exams.

With no electricity and no running water, the premises lack even the most basic facilities, and the handful of toilets used daily by over 1,000 children are unsanitary.

The Iraqi government continues to work on repairing infrastructure damaged by fighting, and electricity supplies have been restored to some parts of Sinjar town but these have not yet reached the school.

A privately owned minibus ferries some children between their homes and the school but many others, whose families cannot afford to pay for the bus, and several of the volunteer teachers, have to walk up to 5km to attend the school.

Children leave afternoon classes at the school (MEE/Abbas al-Karady)

Children leave afternoon classes at the school (MEE/Abbas al-Karady)Volunteer teachers

Azdo is one of only three qualified teachers at the school, only two of whom receive a government salary. The remaining 14 teachers are all young people who have finished secondary school and, despite having no teaching experience, are doing their best to help provide basic education.

«We had to ask people to volunteer to teach in order to save the future of more than 1,000 students, and give them their right to an education,» explained 26 year-old Shevan Khero, the school’s only English teacher and himself a volunteer.

I have just one textbook, so I am gradually writing out the whole textbook on the blackboard, and the children are supposed to copy that down

– Hana Hassan, Arabic teacher

A month ago, there was almost double the number of volunteer teachers but, worn down by the difficult job and with no prospect of financial support, many have left.

Qualified teacher Wahb admits that classes are often so loud and unruly that lessons are feats of crowd-control, with teachers struggling to quiet down overexcited pupils enough to be able to try and teach.

«I volunteered here because I knew the children needed teachers so I was happy to do something to help,» said Arabic teacher Jian Nawaf, 19, who started working at the school in November. «But it’s very difficult because I have 120 pupils in my class and the noise they all make means teaching is almost impossible and, to be honest, I often long for the classes to end.»

Blankets and pieces of carpet keep out the elements (MEE/Tom Westcott)

Blankets and pieces of carpet keep out the elements (MEE/Tom Westcott)Hana Hassan, 21, who also teaches Arabic, admits the job is tougher than she had expected. «I have just one textbook, so I am gradually writing out the whole textbook on the blackboard, and the children are supposed to copy that down, but they don’t all have paper and pens and there are so many children, I can’t even show them pictures and diagrams from the textbook.»

Scant follow-through on NGO promises

Despite the overcrowding, dilapidation and insufficient materials and resources, there is a charming atmosphere in the school and Sinjar’s children say classes are a highlight of their lives, living amidst the tragic ruins of Sinjar.

While his brothers play in the street on a sunny afternoon, seven-year-old Hassan proudly reads aloud from a battered geography textbook pulled from the ruins of a collapsed house. Heavily-scrawled by former students, it has now become a valuable and cherished item. «There are 70 pupils in my class but I love going to school,» he said happily.

«Ninety percent of the pupils here don’t have books or materials for study,» said Khero. «The only way I can teach them English is by speaking and writing on the board because there are no textbooks and most of the pupils don’t have pens or exercise books. It’s very difficult for me but it’s much more difficult for them.»

Sinjar’s overwhelmed and overworked teaching staff were also critical of international NGOs who, they said, despite making numerous visits, have done little more than make empty promises.

«More than ten international organisations have visited the school and seen the situation we face here and they have promised all sorts of things, but nothing ever comes of these promises,» said teacher Bashar Omar Ali.

He said so many NGOs had visited the school, staff struggled to keep up with the names of all the organisations, adding that, since the promises had proved to be only empty words, this was largely irrelevant.

Children wait outside Sinjar school for their parents to collect them (MEE/Abbas al-Karady)

Children wait outside Sinjar school for their parents to collect them (MEE/Abbas al-Karady)UNICEF spokesperson Laila Ali told MEE that during 2017 and 2018, it had supported 10 Arabic schools (3,477 children) and 17 Kurdish schools (5,298 children) across the Sinjar region, providing 106 boxes of educational supplies, and had supported the transportation of over 15,000 school textbooks.

Supplies from any organisation or government, however, have not reached Sinjar town’s only school since the beginning of the school year until now.

Teacher Omar Ali said representatives claiming to be from a UN organisation had made three visits and given extensive promises, including replacing shattered window glass, currently patched up with cardboard or draped with blankets to keep out the elements, and providing much-needed new water tanks. But nothing had yet been done.

Ali, the UNICEF spokesperson, said the organisation had not visited the school nor had not made any such promises.

And even when help does occasionally materialise, said Wahb, this is not always well thought out.

«The last international organisation to visit us made a one-off payment to half the teachers while leaving the other half unpaid, which made a very big problem among the teachers because it was so unfair,» he said.

International aid agencies, mostly working out of Baghdad or Erbil, struggle to provide detailed and accurate accounts of work they have apparently undertaken in the remote Sinjar region, usually carried out by local partner organisations.

Local medics told MEE that work was of a very low standard and often left incomplete, including faulty electrics and broken water systems in one healthcare clinic «renovated» by a major NGO.

*Fuente: http://www.middleeasteye.net/news/worst-school-sinjar-139676923

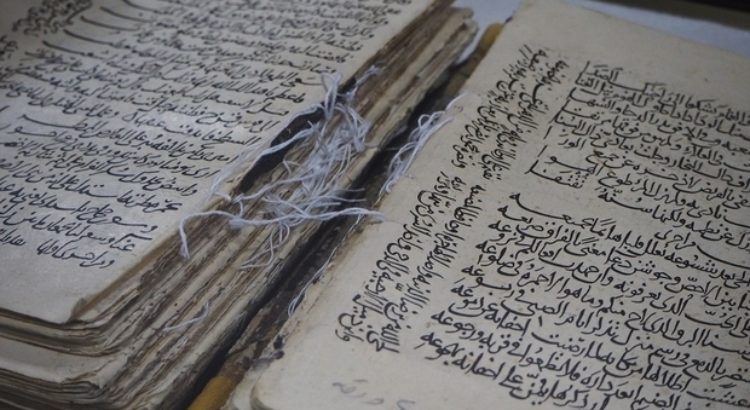

Un Coran écrit et décoré à la main offert à la bibliothèque par la mère du sultan turc Abdülaziz (MEE/Tom Westcott)

Un Coran écrit et décoré à la main offert à la bibliothèque par la mère du sultan turc Abdülaziz (MEE/Tom Westcott) Le bibliothécaire Abdelsalem Abdelkarim estime que la bibliothèque contient entre 80 000 et 85 000 ouvrages (MEE/Tom Westcott)

Le bibliothécaire Abdelsalem Abdelkarim estime que la bibliothèque contient entre 80 000 et 85 000 ouvrages (MEE/Tom Westcott) Le bibliothécaire en chef Abdelmajid Mohamed a aidé à dissimuler les œuvres les plus précieuses de la bibliothèque en 2003 (MEE/Tom Westcott)

Le bibliothécaire en chef Abdelmajid Mohamed a aidé à dissimuler les œuvres les plus précieuses de la bibliothèque en 2003 (MEE/Tom Westcott) Des femmes visitent la tombe du cheikh Abd al-Qadir al-Jilani (MEE/Tom Westcott)

Des femmes visitent la tombe du cheikh Abd al-Qadir al-Jilani (MEE/Tom Westcott) Une copie du Coran à la couverture dorée offerte à la bibliothèque par un fidèle syrien du cheikh Abd al-Qadir al-Jilani (MEE/Tom Westcott)

Une copie du Coran à la couverture dorée offerte à la bibliothèque par un fidèle syrien du cheikh Abd al-Qadir al-Jilani (MEE/Tom Westcott) La bibliothèque contient de nombreux textes astronomiques anciens ainsi que quelques instruments d’astronomie (MEE/Tom Westcott)

La bibliothèque contient de nombreux textes astronomiques anciens ainsi que quelques instruments d’astronomie (MEE/Tom Westcott) La bibliothèque al-Qadiriyya est nichée dans un coin du complexe de la mosquée qui abrite la tombe du cheikh Abd al-Qadir al-Jilani (MEE/Tom Westcott)

La bibliothèque al-Qadiriyya est nichée dans un coin du complexe de la mosquée qui abrite la tombe du cheikh Abd al-Qadir al-Jilani (MEE/Tom Westcott)

Two children walk home after school, past the ruins of Sinjar Old Town (MEE/Tom Westcott)

Two children walk home after school, past the ruins of Sinjar Old Town (MEE/Tom Westcott) Children leave afternoon classes at the school (MEE/Abbas al-Karady)

Children leave afternoon classes at the school (MEE/Abbas al-Karady) Blankets and pieces of carpet keep out the elements (MEE/Tom Westcott)

Blankets and pieces of carpet keep out the elements (MEE/Tom Westcott) Children wait outside Sinjar school for their parents to collect them (MEE/Abbas al-Karady)

Children wait outside Sinjar school for their parents to collect them (MEE/Abbas al-Karady)

Users Today : 37

Users Today : 37 Total Users : 35460340

Total Users : 35460340 Views Today : 53

Views Today : 53 Total views : 3419081

Total views : 3419081