Argentina/5 de julio de 2016/ Fuente: radioamanecer

El bloque de concejales del FPCyS presentó la semana pasada un proyecto de Ordenanza a los fines de establecer el día 12 de junio de cada año como el “Día Municipal contra el Trabajo Infantil” en consonancia con la conmemoración de ese día a nivel internacional.

En el proyecto presentado por los ediles Alicia Perna, Eduardo Paoletti y Emilio Adobatto, pasó a Comisión de Gobierno, y se propone que el Departamento Ejecutivo Municipal sea el encargado de fomentar, a través de la Secretaria que corresponda, el desarrollo de actividades que difundan y promuevan la erradicación del trabajo infantil. Asimismo llevará adelante campañas de concientización durante el transcurso de todo el año.

Dichas campañas deberán desarrollarse principalmente en escuelas, y actividades multitudinarias, garantizando la máxima difusión y tendrán por objetivo principal acrecentar la concientización respecto de la importancia de erradicar el trabajo infantil y de las consecuencias nocivas que el mismo implica para los niños.

Proyecto completo

Artículo 1º) – ESTABLEZCASE el día 12 de junio de cada año como el “Día Municipal contra el Trabajo Infantil” en consonancia con la conmemoración de ese día a nivel internacional.-

Artículo 2º) – DEFÍNESE como Trabajo Infantil a:

Todo aquel trabajo que se realiza por debajo de la edad mínima de admisión a1 empleo fijada en nuestro país que es de 16 años, según Ley 26.390/08 modificatoria de la Ley de Contrato de Trabajo No 20.744, con una etapa transitoria hasta el 2010 que fija la edad mínima en 15 años.

Toda aquella actividad económica por debajo de 10s 18 años que interfieran en la escolarización, en situación forzada, que se realice en ambientes peligrosos o en condiciones que afecten el desarrollo de las niñas, niños y adolescentes.

Artículo 3º) – EL Departamento Ejecutivo Municipal será el encargado de fomentar, a través de la Secretaria que corresponda, el desarrollo de actividades que difundan y promuevan la erradicación del trabajo infantil. Asimismo llevará adelante campañas de concientización durante el transcurso de todo el año.-

Artículo 4º) – DICHAS campañas deberán desarrollarse principalmente en escuelas, y actividades multitudinarias, garantizando la máxima difusión y tendrán por objetivo principal acrecentar la concientización respecto de la importancia de erradicar el trabajo infantil y de las consecuencias nocivas que el mismo implica para los niños.-

Artículo 5º) – A los fines de la presente Ordenanza el Departamento Ejecutivo Municipal deberá celebrar convenios y articular acciones con “La Comisión Nacional para la erradicación del Trabajo Infantil” (CONAETI) y con la “Comisión Provincial para la prevención y erradicación del Trabajo Infantil”(COPRETI). Asimismo deberá celebrar Convenios con el Centro Industrial y Comercial, Ministerio de Trabajo de la Provincia de Santa Fe, Universidades y/o Organismos pertinentes, a los fines de efectuar un relevamiento en todas las empresas del Distrito Reconquista y todos aquellas personas físicas registradas como empleadoras, con el objeto de detectar irregularidades relacionadas con esta problemática.-

Artículo 6º) – El Departamento Ejecutivo Municipal, deberá además, a través de la Secretaría que corresponda, confeccionar un registro que contenga los datos de todos aquellos menores que se encuentren sin la presencia de un adulto en la calle realizando alguna actividad con el fin de recaudar dinero. Recolectados los datos, el Ejecutivo, a través del área de Niñez, Adolescencia y Familia, deberá mandar una Asistente Social a la dirección denunciada por dicho menor a los fines de recabar la mayor cantidad de datos posibles sobre la situación socio-familiar, educativa y de salud de los referidos menores y actuar con el objetivo de garantizar el efectivo cumplimiento de los derechos de los niños, niñas y adolescentes.

Artículo 7º) – COMUNÍQUESE al Departamento Ejecutivo Municipal.

Fundamentos

“El trabajo infantil no tiene cabida en mercados que funcionen bien y estén bien regulados, ni en ninguna cadena de producción. El mensaje de que el trabajo infantil ya no puede ser tolerado y debe ser combatido con urgencia fue confirmado por los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible. Actuando juntos, podemos hacer del futuro del trabajo un futuro sin trabajo infantil.» (Director General de la OIT, Guy Ryder)

El 12 de Junio, se conmemora el Día Mundial contra el Trabajo Infantil, y desde 2002, la Organización Internacional del Trabajo (OIT) designó esa fecha con el objetivo de brindar una mayor visibilidad al tema y destacar el movimiento mundial para eliminar el trabajo infantil, en particular en sus peores formas. Sabido es que el trabajo infantil es una de las peores formas de explotación y abuso. Pone en peligro la salud, seguridad y educación de los más chicos, al mismo tiempo que atenta contra su desarrollo físico, mental, espiritual, moral y social.

En nuestro país en 1907 el Congreso Nacional aprobó un proyecto de Ley presentado por el Legislador Alfredo Palacios para reglamentar el trabajo de las mujeres y los niños; se proponía proscribir el trabajo nocturno y abolir el trabajo a destajo para los varones menores de 16 años y para las mujeres menores de 18 años. El mismo declaraba: . . . «las mujeres que trabajan en nuestras fábricas son en casi su totalidad niñas que recién han llegado a la pubertad, he entrado en las fábricas y he podido observar todo el peligro que encierra; esos niños que vienen del seno de la madre con la marca de la injusticia, van a ser también requeridos por la máquina que cruje en el taller y pide a gritos carne de pueblo…”

Asimismo, en el ámbito internacional el 20 de Noviembre es el Día Universal de 1os Niños y las Niñas, en el cual se conmemora la fecha en que la Asamblea General de las Naciones Unidas aprobó la Declaración sobre 1os Derechos del Niño en 1959 y la Convención sobre los Derechos del Niño en 1989, con rango constitucional desde 1994. Dicha convención considera a todo niño, niña y adolescente como sujeto de derecho, poniendo en discusión otras representaciones que los han relacionado con la incapacidad, la tutela, el objeto y cuidado.

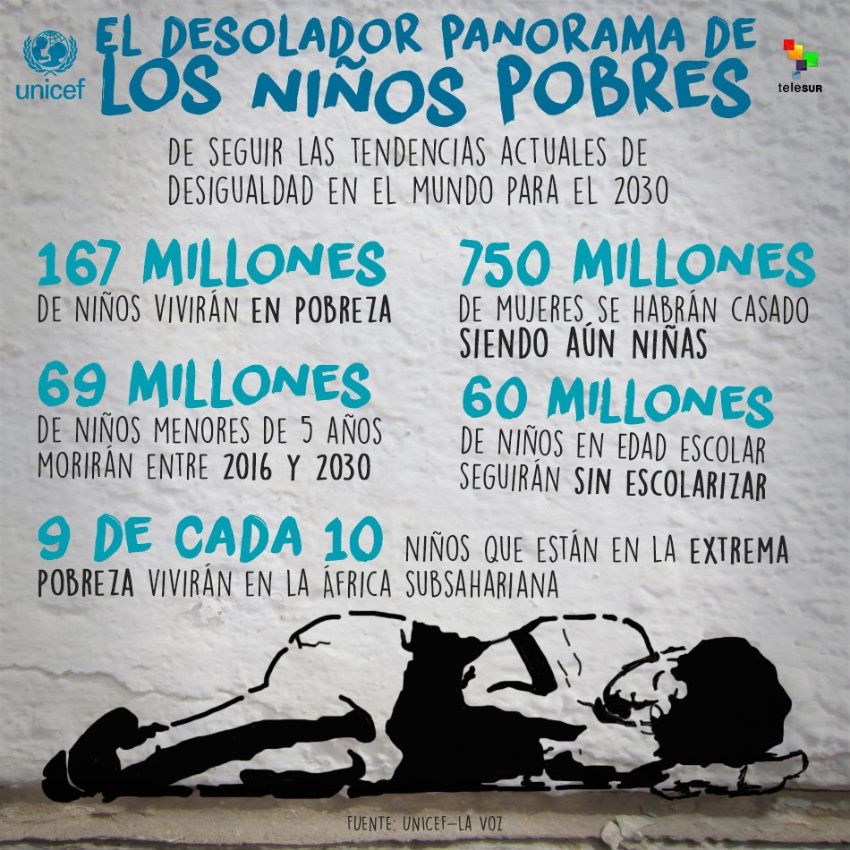

Recurriendo a las cifras, según los reportes de la UNICEF, alrededor de 246 millones de niños y niñas son sujeto de explotación infantil en todo el mundo, estando relacionada esta problemática con la trata de niños y niñas, sea interna o entre países y continentes, generándose así una situación muy compleja que necesita de un abordaje integral. Sin embargo, las cifras disponibles no reflejan toda la magnitud del problema, debido a la invisibilidad de labores, como el trabajo doméstico, y de formas intolerables, como la explotación sexual, así lo asegura la directora local de la Organización Internacional del Trabajo (OIT), Ana Lía Piñeyrúa (2004). En este sentido y sólo en el ámbito urbano 1os niños trabajan en obras de construcci6n, recolección de botellas, cartones, papeles y otros residuos o desperdicios, elaboración y venta de alimentos en la calle, reparto de estampitas a cambio de dinero, venta callejera de diversos artículos (golosinas, flores, etc.) y forman parte del oscuro mundo de la prostitución infantil y el crimen organizado.

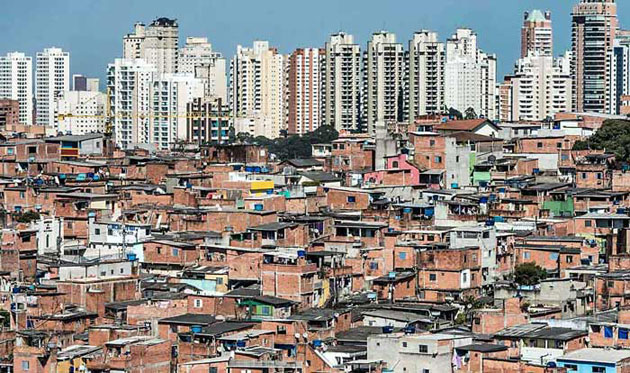

Al respecto, las principales causas del Trabajo Infantil son: a) la pobreza que impulsa a las familias a utilizar toda la fuerza laboral disponible para la subsistencia; b) factores sociales y culturales, que implican una apreciación positiva del Trabajo Infantil como un modo de aprendizaje y preparación para la vida adulta, otorgándole un valor superior en detrimento del otorgado a la escuela; c) la permisividad social frente a situaciones de Trabajo Infantil visible; d) la existencia de trabajos no registrados y un sistema insuficiente de controles por parte de los estados. Las referidas causas producen consecuencias en aspectos sociales como la profundización de la desigualdad, la violación de los derechos fundamentales de la infancia y la adolescencia, el impedimento y la limitación del adecuado proceso educativo y el condicionamiento del nivel de ingresos en la vida adulta; además de causas en aspectos de salud como son las enfermedades crónicas.

Existen dos posturas claramente diferenciadas sobre el trabajo infantil. Por un lado, están quienes abogan por la prevención y erradicación, estos sostienen que el trabajo infantil perpetua el circulo vicioso de la pobreza y que la realización de algún trabajo por debajo de la edad mínima perjudica, obstaculiza e impide el desarrollo físico, mental, espiritual y social de los niños y niñas que se ven sometidos/as a esta realidad tristemente naturalizada en las sociedades subdesarrolladas, tal es el caso de nuestra sociedad. Por otro lado están los que postulan la protección y dignificación del trabajo infantil, como una experiencia positiva desde el punto de vista de la socialización, del aprendizaje y de la identidad psicosocial del niño o niña, afirmando que el reconocimiento de éstos como actores sociales, refuerza su autoestima y permite genera un proyecto de infancia alternativo. La Organización Internacional del Trabajo (OIT) dentro de 1os parámetros del trabajo decente y digno, postula la erradicación del trabajo infantil, además del trabajo registrado y la igualdad de trato, y es importante adherir a estos postulados.

En nuestro país la Ley 26.390 prohíbe el trabajo infantil y en la provincia de Santa Fe, la Ley 12967 (2009) de Promoción y Protección Integral de los Derechos de los Niños, Niñas y Adolescentes brinda un amplio marco de derechos para los niños, niñas y adolescentes, entre 0 y 18 años. Dicha normativa reconoce formalmente sus derechos y define criterios y modos de actuación del Estado provincial, adecuados al modelo de protección integral de derechos.

Es nuestro deber como Organismo del Estado y como ciudadanos controlar y garantizar el efectivo cumplimiento de los derechos de los niños. Tal como lo menciona el Director General de la OIT, el trabajo infantil no debe ser tolerado y debe ser combatido de manera urgente, hay que intensificar los esfuerzos para extender la protección social a fin de mantener a los niños alejados del mismo, y asegurarnos de que los niños sean “niños”.

Fuente: http://radioamanecer.com.ar/2016/07/presentan-proyecto-para-promover-la-erradicacion-del-trabajo-infantil/

Imagen: http://www.americasolidaria.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/trabajo-infantil-bolivia-DW-com.jpg

Users Today : 14

Users Today : 14 Total Users : 35460367

Total Users : 35460367 Views Today : 20

Views Today : 20 Total views : 3419120

Total views : 3419120