México/ 09 junio 2016/ Autor: Horizontal/ Fuente: Insurgencia Magisterial.

La reforma educativa culpó al magisterio de todos los problemas del sistema. En este proyecto laboral se desperdició un impulso histórico para transformar verdaderamente la educación en México.

A propósito de las últimas tensiones entre el magisterio y el gobierno, entrevistamos a Manuel Gil Antón, profesor investigador del Colegio de México, sobre el contexto actual del sistema educativo mexicano, los saldos de las evaluaciones, la relación entre el sindicato y el Estado y los prejuicios que acompañan la percepción social del maestro.

¿Nuestro sistema educativo en lugar de contribuir a la equidad social es impulsor de la desigualdad?

Aprendí de un colega que una mirada hacia el sistema educativo podía ser por el lado de la equidad. Este enfoque tiene dos objetivos fundamentales: que nadie tenga obstáculos para acceder a la educación obligatoria y, segundo, que se rompa la distancia entre origen y destino. Por el lado del acceso estamos terriblemente mal: hay seis millones de analfabetas, 10 millones sin primaria, 16 millones sin secundaria –y estos 32 millones son el 43% del grupo de 15 a 64 años de México. Entonces por el lado del acceso tenemos un acceso muy sesgado por las condiciones económicas. Y, por el otro lado, el que pretende que la educación rompa la determinación del origen social sobre el destino laboral y el avance cognitivo, pues no podríamos estar peor: padres con posgrado tienen hijos en licenciatura, padres sin instrucción tienen hijos que no terminan primaria. En este contexto, si nosotros tenemos una desigualdad social tan aguda, la escuela para propiciar igualdad tendría que dar la mejor educación a los que más lo necesitan y creo que el país está dando la peor educación a los que más lo necesitan (en términos de infraestructura, de condiciones y riqueza de materiales y recursos pedagógicos). A los que más tienen se les da la mejor educación –o la pueden pagar–, y a los que menos tienen se les da la peor educación (por ejemplo, el 40% de las escuelas primarias en México son multigrado: un profesor o dos atienden a todos los grupos). En consecuencia, el abandono escolar está concentrándose en los sectores más desfavorecidos, a los cuales el título de “certificado” les podría significar avance. Si esto es así –y la investigación apunta a ello– el sistema educativo no está promoviendo un proceso mediante el cual tú puedas tener credenciales con las que aspires a una movilidad social –sobre todo cuando dejas la educación en una etapa temprana–, sino que te coloca otra vez en desventaja. En este sentido, el sistema educativo no solamente sigue la curva de la desigualdad sino que la incrementa, la potencia.

¿Qué otros elementos complementan tu diagnóstico del sistema educativo?

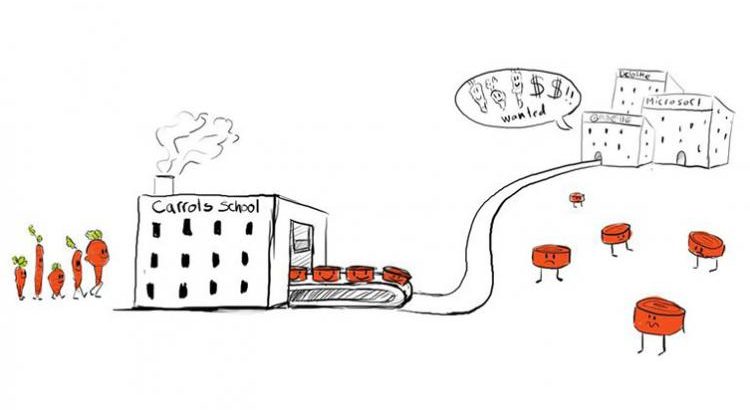

Si lo ves desde el punto de la equidad, el anterior sería el problema principal. Si lo ves desde el punto del aprendizaje, de nuevo, los que no se van de la escuela y que permanecen en ella hasta el bachillerato, más o menos el sesenta por ciento, no tienen capacidad ni de lectura ni de escritura después de 12 años, y si te fijas en quiénes son esos que, a pesar de haberse sostenido en una escuela que es expulsora, terminan, notas también un sesgo, un impacto de la clase de origen. De tal manera que si la promesa de toda escuela en una sociedad moderna es contribuir a pasar de una dinámica de roles adscritos por nacimiento a una de roles adquiridos por mérito, en México parece ser mucho más explicativo del futuro de una persona su origen social (“origen es destino”). Por otro lado, más vale tener conocidos que conocimiento porque, aun los que terminan y tienen certificados, van a tener más dificultades para encontrar un empleo, pues no tienen redes de contacto en un país que, a su vez, no tiene empleo. Por el lado de la equidad pero también por el lado del aprendizaje se ha despreciado el impacto que tienen pésimos planes y programas de estudio, que son extraordinariamente ricos en información a repetir y poco profundos en la consolidación de estructuras cognitivas que permitan preguntar. Entonces, el sistema educativo, creo, está generando con mucha frecuencia repetidores (porque además ese es el modo de evaluar) y no gente que sepa plantear una pregunta (para plantear una pregunta tienes que comprender, que tener otros insumos). Un sistema así lo que genera es una suerte de carrera de obstáculos para seguir pasando la escuela.

En breve, ¿cuál es tu tesis sobre la reforma educativa?

En general, lo que yo pienso es que la reforma educativa simplificó el problema en el magisterio y supuso que un magisterio mejor preparado (o mejor evaluado), por ese hecho, iba a mejorar la calidad de todo el sistema. El factor que aporta el profesor en el aprendizaje no es menor pero es muchísimo menor que el que aportan, por ejemplo, la desigualdad, el desastre en los planes y programas de estudio y la centralización del proceso.

¿Qué detalles específicos te preocupan de la reforma educativa?

Hablaré para empezar de dos, uno menor y otro grave: la alteración del artículo 3 de la Constitución y, segundo, la alteración del artículo 73 y su subsiguiente traducción en la Ley General de Servicio Profesional Docente.

Con la reforma educativa los legisladores incluyeron el adjetivo “calidad” en el artículo 3 de la Constitución, en lo que es un claro pleonasmo. Según el adagio jurídico de “justificación no pedida, acusación manifiesta”, el hecho de que en el texto constitucional se diga que la educación que imparte el Estado tenga que ser de calidad es muy desalentador, porque no tendría que tener ese calificativo: que sea obligatoria, gratuita, laica, etcétera, son calificativos, en efecto, del tipo de educación que el Estado hace cuando es un Estado moderno, no confesional, pero si se tiene que repetir que es de “calidad” y que esto es necesario que esté en la Constitución significa que no lo era –o hay que decir que lo sea. Probablemente sea más un lapsus para interpretación de los psicoanalistas que de los sociólogos.

La segunda cuestión la considero aguda. En el artículo 123, que regula la cuestión laboral, tenemos un apartado “A” y un apartado “B”. El apartado “A” es para los trabajadores de la industria y el apartado “B” para los trabajadores al servicio del Estado. Al reformar el artículo 73, es decir, el artículo sobre las facultades del Congreso, quedó, en la fracción XXV, que el Congreso de la Unión es el encargado de regular los términos de ingreso, promoción y permanencia del personal docente. Esto quiere decir que los docentes están fuera de la regulación laboral: están en un régimen laboral de excepción. Por poner un caso histórico, durante mucho tiempo el doctor Guillermo Soberón, de la UNAM, propuso que para los trabajadores universitarios debería haber un apartado “C” (por la naturaleza de su trabajo, etc.), cosa que no se logró. En este caso, sin decirlo, hoy el magisterio mexicano está en un régimen laboral de excepción porque cuando se fracase las veces que estipula la ley, por ejemplo, en aprobar un examen, se termina la relación laboral sin ninguna responsabilidad para la autoridad –y no hay ni siquiera liquidación. Creo que no se ha pensado lo suficiente qué significa tener al magisterio en un apartado específico.

Esto es un problema porque luego, traducido en la Ley de Servicio Profesional Docente, propone que los profesores que antes gozaban de la estabilidad en el empleo ahora cada cuatro años tendrán que refrendar su posibilidad de seguir siendo profesores. Esta es una renovación cuyos incentivos no están orientados a ver en qué podría mejorar el profesor, sino a ver cómo podría conservar el empleo. Es una precarización de las condiciones laborales hasta el infinito. En la educación superior, por ejemplo, cuando tienes una base, pues tienes estabilidad en el empleo. Si faltas tres veces te pueden correr pero, vamos, no se necesitaba hacer una reforma educativa para aplicar las sanciones que corresponden a la ley de trabajo. A mí me parece grave, como un signo de los tiempos, que se precarice el trabajo. Por esto, ligo esta reforma educativa con la reforma laboral que hicieron en el interregno entre Calderón y Peña Nieto para facilitar el despido.

Entonces, el fracaso de la reforma educativa se debe a que se enfoca exclusivamente en los maestros.

Sí: los implica al culparlos, como si fueran un factor único o el principal. La reforma supone que por evaluarlos va a subir la calidad de sus clases. Y aquí la propuesta que hemos hecho muchos es que si la evaluación tiene como efecto perder el empleo, entonces las personas se van a preparar para la evaluación sin que esto tenga un correlato en el cambio de la práctica pedagógica. En sociología existe la famosa ley de Campbell, que dice: mientras más precisa sea una métrica para evaluar algo, mientras más consecuencias fuertes tenga, esta métrica va a ser, al mismo tiempo, cumplida y, en la misma proporción, simulada. Entonces lo que estamos viendo ahora es la proliferación de un montón de entidades y empresas que te preparan para la evaluación, pero que no son espacios para mejorar la actividad en el aula, sino para ayudarte a sobrevivir en el empleo.

¿Cómo llegamos a este punto? ¿Por qué la reforma solamente se enfocó en los profesores?

Me parece que en los años previos a la reforma educativa se fue construyendo una generalización muy injusta, un prejuicio, de que todo el magisterio eran un grupo de golpeadores, ignorantes, ineptos, una generalización incluso con notas clasistas y racistas. Recuerdo a varios personajes de los medios de comunicación diciendo “¿Usted dejaría a sus hijos con esa persona?” –cuando “esa persona” tenía el fenotipo de las personas de Oaxaca y Chiapas. También está la simplificación del convenio corporativo entre el Estado y el sindicato, del cual se culpa solo al sindicato, como si en el caso de Oaxaca Ulises Ruiz o Diódoro Carrasco no tuvieran nada que ver en esa convivencia –o los secretarios de estado o Elba Esther. Entonces, el traslado de la culpa del acuerdo a un solo polo, sumado a la construcción de una imagen de los maestros como unas personas muy mal preparadas, incapaces e ignorantes, generó en la opinión pública la idea de que bastaba con evaluarlos, para que se pusieran a estudiar y que todo el sistema mejorara. Creo que esta no es la solución. Y ese estigma, esa forma de generalizar, por lo menos, con un conjunto de un millón doscientas mil personas, diciendo que todos son ignorantes, que todos son unos provocadores, que todos son violentos, etcétera, permitió que la reforma pasase con facilidad y que su objetivo único sea controlar al magisterio.

Caricatura de Paco Calderón.

Se desperdició un impulso histórico en una reforma educativa limitada.

Lo más triste es que la reforma educativa es necesaria, pero concibiéndola como la transformación de las condiciones en las que ocurre el aprendizaje, que rebasan al profesor aunque lo incluyen. Por un lado, hay una resistencia fuerte, muy localizada, que incluso ha llegado a niveles de mucha polarización. Por el otro, hay una resignación: si tengo que conservar el empleo, hago la evaluación y me preparo para la evaluación, pero que me prepare para la evaluación no tiene consecuencias en lo que hago como maestro. Por lo tanto, nuestros déficits en el aprendizaje no van a subsanarse por evaluar cada cuatro años a doscientas cincuenta mil personas.

Además, los profesores salieron bien en las evaluaciones.

Esa es una cuestión de la que vale sospechar. Algunos evaluadores con los que he podido hablar me han dicho que los resultados eran malos, pero que la calificación de corte de lo que se consideraba satisfactorio o insatisfactorio se ajustó a lo que podía aguantarse políticamente. En cierto modo, cuando la reforma culpa al magisterio y luego el ochenta y cinco por ciento de los resultados de las evaluaciones son buenos o destacables, pues se contradice. Pero hay quienes opinan que se fue demasiado generoso en la calificación de satisfactorio en adelante para evitar un problema político fuerte.

Independientemente de los resultados, nos tendríamos que preguntar si es idónea la evaluación. Cuando a un profesor le piden que suba cuatro evidencias de su trabajo, luego que haga un examen de conocimientos y luego que haga una planeación pedagógica en la mañana, lo recopilado nos puede decir cosas: puede decir cuánto domina del conocimiento, puede darnos una idea de qué tan capaz es didácticamente, pero con eso no puedes decir que durante 16 años ese profesor ha tenido un desempeño “excelente” o “destacado” o “insatisfactorio”. No se puede: a veces he dicho que es tratar de medir la presión arterial con un martillo. Porque esa evaluación sí diría cosas que podemos mejorar, pero predicar que ella nos puede calificar el desempeño de años de trabajo no es adecuado. Y esto es lo que se está viviendo.

¿Cuál es el escenario próximo?

Me parece que la reforma va a ser exitosa en términos de la renovación del pacto corporativo del gobierno federal con el sindicato. Es impresionante como cada que sale en imagen Aurelio Nuño, el secretario de educación pública, sale también Juan Díaz de la Torre, el secretario general del Sindicato Nacional de Trabajadores de la Educación (SNTE). Que este último haya visto cómo todo su gremio ha perdido la estabilidad en el empleo y que el sindicato no haya hecho ninguna objeción, me parece que indica la reconstrucción del pacto corporativo que se había roto, que se había roto porque Elba Esther se había ido, digamos, a vender al mejor postor sus servicios políticos. La posición del SNTE ha sido la de decir: “nosotros le aseguramos al profesor que lo preparamos para que vea que no va a perder su empleo”. Nunca se ha pronunciado sobre la pérdida de la estabilidad laboral del gremio. Ni siquiera ha propuesto que después de tres o cuatro evaluaciones se gane la estabilidad. En sentido estricto, si cada cuatro años no tienes seguro el empleo y tienes que ser revisado, no podrías obtener, por ejemplo, un préstamo del ISSTE. Entonces, me parece que la reforma va a producir una reorganización política en la relación entre el Estado y el sindicato y no va a tener consecuencias significativas en el aprendizaje y, por otro lado, está generando una polarización importante (como vimos en el caso de Chiapas); las evaluaciones están siendo casi militarizadas: tienen que meter un montón de policías para que se puedan llevar a cabo y la vejación que sufrieron los profesores en Chiapas, en días pasados, nos habla de un nivel de encono muy grande. En cierta medida, me parece que los profesores van, en general, a aceptar como una forma de adaptación a nuevas reglas para conservar el empleo, sin estar convencidos que esa evaluación es significativa en su desarrollo, como lo han hecho tantas veces: de repente la SEP dice “vamos a ser constructivistas” y son constructivistas; dos años después dice “vamos a ser ahora por competencias” y son por competencias. Y, en realidad, está pasando lo mismo.

¿Cómo ves el contexto de Chiapas y Oaxaca?

A mí me parece que ahí –en Chiapas, Oaxaca, Guerrero y Michoacán, donde la Coordinadora Nacional de Trabajadores de la Educación (CNTE) es muy fuerte– la labor del profesor es una labor que incluye, además de la enseñanza (con sus fallas, sin duda), una especie de liderazgo social ante la miseria y la injusticia. Casi siempre confundimos a los profesores con la cúpula de la coordinadora o a los profesores con la cúpula del sindicato –me parece que esto es un error. Cuando el gobierno actual dice, por ejemplo, que en Chiapas o Oaxaca el profesorado tenía condiciones de privilegio, habla como si esas condiciones hayan sido arrebatadas por el sindicato y no pactadas por el gobierno; ninguna plaza o prestación que le dieron al Instituto Estatal de Educación Pública de Oaxaca (IEEPO), cuando tenía bastante influencia en él la sección 22 del sindicato, careció del acuerdo con el gobernador; entonces si para obtener un préstamo a la vivienda la sección 22 pedía ser activo políticamente en las manifestaciones, pues en las otras secciones también para obtener prestaciones se tenía que tener una cierta disciplina con la vida sindical. Yo creo que tenemos un magisterio sumamente atrapado en el sindicalismo, ya sea el sindicalismo al servicio del poder o un sindicalismo que propone desde la escuela la transformación social de toda la sociedad, lo cual creo que es un exceso. Entonces, la coordinadora que surge para democratizar la forma de elección de la secretaría general del SNTE, poco a poco, se ha convertido en una instancia que tiene un proyecto de educación que incluye la transformación social. Quizás arriba, los dirigentes puedan tener pactos y acuerdos y privilegios, pero creo que estamos desperdiciando que muchos profesores de base sostienen eso –educar para lograr la transformación la sociedad– como convicción genuina. Y ante esto, hay que tener más habilidad política; no basta con simplemente exigirles una evaluación.

En 2013, Claudio Lomnitz propuso renovar las formas de resistencia magisterial. Una de sus propuestas era librar, con argumentos y propuestas, una batalla de inteligencia en la opinión pública. ¿Crees que se ha librado esta batalla?

A nivel de opinión pública, me parece, lo que ha ocurrido es que fue tan fuerte la desacreditación del magisterio que la posibilidad de que el propio magisterio mostrara que había muchos profesores que han hecho un trabajo diferente no ha sido posible. Doy un caso. Varias veces fui el programa de Leo Zuckermann, Es la hora de opinar, y cada que terminaba el programa terminaba él diciendo: “Oye, a ver, Manuel, por qué no la próxima vez traemos a profesores para que ellos digan cómo están viviendo la reforma”. En varias ocasiones se propuso. A mí me dijo: “¿Tú puedes conseguir que vengan profesores?” Le dije que “sí” y lo mismo le preguntó a David Calderón, de Mexicanos Primero, que también accedió. Está bien, quedamos en escuchar a los profesores, en vez de escuchar a los “intelectuales” que disque sabemos de esas cosas. Pero ese programa nunca ocurrió. Yo no he visto a profesores de base decir cómo están viviendo la reforma. Por eso, me parece que lo que propone Claudio de ir a ganar en la opinión pública la percepción de una reforma necesaria no ha ocurrido porque, en general, los medios se han comprado y contribuyeron a crear la imagen de que del magisterio no se puede esperar nada y que, por eso, hay que someterlo. Ese es el verbo que utiliza el secretario Nuño: “aquel que no se someta a la evaluación, perderá el empleo”. Entonces, me parece que esa batalla en los medios está perdida. Hay –en La Jornada y en algunas otras columnas– personas que tratamos de decir, bueno, aquí hay carencias, esta evaluación no es idónea, que es cierto, es constitucional, es legal, pero hay problemas, hay que discutirla. Son voces minoritarias; en la mayoría de los canales de televisión, en la mayoría de los medios, han difundido la otra versión.

Con los hechos de Chiapas y Oaxaca, ¿los medios están volviendo a difundir los prejuicios que citas?

También hay que reconocer que la coordinadora no ha sido creativa en sus modalidades de protesta, por lo que está perdiendo apoyo social. Curiosamente, con sus acciones fortalece la idea de que todos los profesores son una bola de violentos. Cuando hablas con algunos de ellos te dicen: “A ver, si no cerramos las calles, nadie nos hace caso. Si no hacemos los bloqueos, ¿quién hubiera discutido la reforma?” La reforma educativa la aprobaron todos los partidos por unanimidad. ¿Qué partido en el Congreso dijo “oigan, perdón, esta es una simplificación enorme”? En ese momento no había Congreso en México: estaba sustituido por el Pacto por México. Y ahí la reforma surge y luego llega a las cámaras a ser aprobada. Hay una especie de ajuste que el PRD procura sobre la cuestión de la estabilidad pero es algo menor (y además suscitado por la movilización del magisterio). Es curioso: la reforma que tuvo más resistencia fue la educativa, no la energética (cuando se pensaba que esta iba a despertar un resurgimiento del sentimiento nacionalista), principalmente porque la educativa tocó a un sector organizado. Pues sí, en los medios uno siempre ve la fotografía del profesor violento –nunca ves la fotografía, por ejemplo, de una profesora que va marchando inconforme. Hay toda una construcción imaginaria del magisterio como un sector violento.

¿Cómo explicar el aumento de la popularidad de Aurelio Nuño?

Si nosotros hacemos el seguimiento de la estigmatización del magisterio y luego aceptamos que se ganó en la opinión pública la idea de que la evaluación es el único camino, entonces el secretario Nuño está siendo visto como un tipo que no negocia la ley, cuando durante años con el CNTE y la SNTE se negoció cualquier cosa: no solo la ley, se negociaban elecciones. Me parece que el secretario Nuño está siendo mirado como un político que hace cumplir la ley, un político que no negocia la ley, y esto está teniendo un impacto en la apreciación de su gestión. No me extraña la satisfacción que generó entre algunos sectores el proceso a Elba Esther. Si haz construido al diablo durante años y luego lo metes a la cárcel, pues claro que te ganas adeptos; si haz concebido al magisterio como el diablo –porque son burros, ignorantes, desgraciados y toman casetas– pues evalúalos, somételos, y el que no se deje someter, córrelo.

Entonces el secretario está personificando, a mi juicio, lo que muchos considerarían el Estado de derecho. Y eso le va a dar rendimientos, salvo que la represión que se suscite haga inviable su continuidad. Pero sí: está teniendo el aprecio de muchos sectores de clase media, de muchas personas que dicen “que se evalúe y el que no se evalúe que se vaya”. En este sentido, el riesgo que puede ocurrirle es que abandone una de las cuestiones más preciadas de la política que es la capacidad para abrir espacios de diálogo. Pero, bueno, él ha jugado a la lógica de hacer cumplir la ley y las amenazas de despidos se han cumplido. Vamos a ver qué pasa en Chiapas, qué pasa en Oaxaca, cuando en efecto se despidan a los profesores, vamos a ver cómo reacciona el gremio, porque hasta ahorita solo hemos visto las reacciones del gremio ante la evaluación. Ayer me decía una profesora que es supervisora: “El problema, Manuel, de esta reforma es que no se pone la autoridad en nuestro pellejo; yo soy profesora y yo tengo la obligación de parte de SEP de señalar qué profesores no fueron a trabajar, a quienes van a despedir; y yo voy a seguir viviendo ahí con mi familia; Nuño y Peña se van a ir”. Entonces, la situación abajo, entre quienes efectivamente despiden a los profesores, pues la están viviendo los supervisores y los directores y yo creo que eso va a generar mucho encono. Por otro lado, también decir que este profesor es “destacado”, que este es “bueno”, que este no, está estratificando al magisterio. Son muchas aristas las que tiene la implementación de la reforma. Y yo sí pienso que para muchas personas una persona de mano firme como Aurelio Nuño está siendo muy bien recibido por sectores que consideran que lo que necesita este país es “mano firme” (Chong dice “firme”, no “dura”).

Una de los aspectos que no se han tocado en la reforma es este: ¿cómo puede un gobierno con tal nivel de corrupción conducir una reforma educativa que, en el fondo, tiene que ser una reforma ética? Yo no conozco –y te lo dicen los empresarios y te lo dice todo mundo– un nivel de impunidad y de corrupción más grande como el de esta administración y, sin embargo, son los que impulsan la reforma educativa. ¿Con qué autoridad moral?

Has hablado en otras ocasiones que la reforma debió buscar descentralizar el sistema. ¿Podrías desarrollar esta idea?

Aprendí esto de la profesora Coral, la directora de una Telesecundaria de la sierra, que termino en uno de los foros diciendo: “Miren, si de veras quieren que progrese la educación, no le hagan caso a la SEP”. Es algo más que una anécdota la idea de que las reformas educativas que han resultado fuertes y relevantes en las experiencias en el mundo han sido las que han confiado en el magisterio y han descentralizado los esfuerzos para que sean las comunidades –de profesores, alumnos y padres de familias– las que decidan y tengan proyectos escolares. Creo que esta reforma es muy centralista, muy uniformadora. El Instituto Nacional para la Evaluación de la Educación (INEE) está haciendo parámetros generales que quiere hacer valer, pues, en escuelas multigrado y en escuelas urbanas, cuando son contextos diferentes (no quiero decir que a las escuelas multigrado no se les tenga que exigir que sean buenas, pero sí tienen circunstancias de trabajo diferentes). El problema es complejo. Pero yo remataría diciendo que no hay reforma educativa que haya prosperado si consideran que el magisterio es un objeto a transformar y no un sujeto aliado de la reforma; y como esta reforma lo considera un objeto, un insumo a calificar y evaluar, me parece que el magisterio o se va a resistir o va a adaptarse a la evaluación, sin comprometerse a un cambio. Por eso, la idea era tratar de ver si podíamos hacer una reforma más descentralizada; por ejemplo, pidiendo a zonas y regiones escolares que hicieran un compromiso con unos objetivos a cumplir en seis años, con sus propios medios pedagógicos, como que después de ese periodo en su zona no haya ningún niño que no sepa leer y escribir. Esa idea de una reforma que confíe más en el magisterio tendría, sí, que vigilar las zonas donde esa libertad se convirtiera en el apoyo a la desidia. Pero me parece que tendría más impacto en la vida cotidiana de las escuelas si se confiara y se corrigieran las desviaciones, en lugar de tratar que todo cambie desde arriba. Esa era la idea –no veo que venga.

Manuel Gil Antón es profesor investigador del Colegio de México. Se puede consultar su trabajo académico aquí y sus artículos de opinión aquí.

Fotos: cortesía de Galo Naranjo, alisa, Eneas De Troya y Malova Gobernador.

Fuente: http://horizontal.mx/sobre-el-fracaso-de-la-reforma-educativa-entrevista-a-manuel-gil-anton/

Fotografía: boisestatepublicradio

Fuente de la Entrevista:

http://insurgenciamagisterial.com/sobre-el-fracaso-de-la-reforma-educativa-entrevista-a-manuel-gil-anton/

Users Today : 28

Users Today : 28 Total Users : 35474869

Total Users : 35474869 Views Today : 55

Views Today : 55 Total views : 3574964

Total views : 3574964