Canadá/Agosto de 2017/Fuente: Huffpost

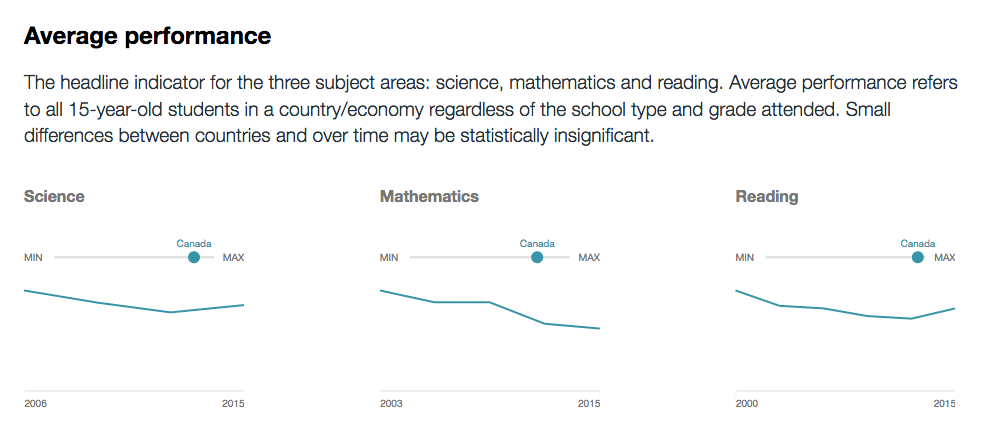

Resumen: En el artículo publicado el 2 de agosto por la BBC, «Cómo Canadá se convirtió en una superpotencia de la educación», Sean Coughlan toma los resultados de la evaluación de la última prueba PISA y concluye que Canadá es una «superpotencia de la educación». Los resultados del rendimiento de 2015 indican que Canadá ha subido al nivel más alto de los rankings internacionales y está en la posición número 10 en matemáticas, lectura y ciencia. A nivel universitario, Canadá tiene la proporción más alta del mundo de adultos en edad laboral que han pasado por la educación post-secundaria – 55 por ciento en comparación con un promedio en los países de la OCDE de 35 por ciento. Más de un tercio de los adultos jóvenes en Canadá son de familias donde ambos padres son de otro país. Los hijos de las familias migrantes recién llegadas parecen integrarse rápidamente y desempeñarse al mismo nivel que sus compañeros de clase. La variación de las calificaciones en Canadá causada por los estudiantes «favorecidos» y «desfavorecidos» era baja y las diferencias socioeconómicas en Canadá eran del 9%, frente al 20% en Francia y el 17% en Singapur.

Cherry picking a single test point and creating a generalization based on a single set of data can lead to inaccurate assessments and conclusions. In the article published on August 2 by the BBC, «How Canada became an education superpower,» Sean Coughlan takes assessment results from the latest PISA test and concludes Canada is an «education superpower.»

Coughlan uses the following reasons to give Canadian education such an honorary standing:

- 2015 performance results indicate Canada has climbed into the top tier of international rankings and is in the top-10 position in math, reading and science.

- At university level, Canada has the world’s highest proportion of working-age adults who have been through post-secondary education — 55 per cent compared with an average in OECD countries of 35 per cent.

- More than a third of young adults in Canada are from families where both parents are from another country. Children of newly arrived migrant families seem to integrate quickly and perform at the same level as their classmates.

- The variation in scores in Canada caused by «advantaged» and «disadvantaged» students was low, and that socio-economic differences in Canada was nine per cent, compared with 20 per cent in France and 17 per cent in Singapore.

Thank you for the gracious pat on the back, Mr. Coughlan and the BBC, but let’s look at more data before our Canadian school policy makers and universities believe their «achievements.»

Where other countries are systematically and carefully investing in their education, we are falling behind.

International assessment rankings

Looking at the historic data dating back to early 2000s, Canada’s performance on PISA tests is in decline. We are definitely not climbing any ranks. In PISA 2003, only two countries performed better than Canada on the combined mathematics scale. In PISA 2015, Canada ranked in the 10th position. Our students today aren’t as strong in their knowledge and problem-solving skills as those who took the test a decade earlier, and we have been outranked by more than a handful of countries during this time.

(Source: PISA 2015)

The downward trend isn’t only in our PISA scores. Two Chinese universities took giant steps forward in the 2017 Times Higher Education World University Ranking and outranked the University of British Columbia and McGill University, two of Canada’s top universities. In the midst of global competition where other countries are systematically and carefully investing in their education, we are falling behind.

Canada’s high proportion of working-age adults with post-secondary education

Pumping out post-secondary students doesn’t say much about the health of a country’s education system. Post-secondary studies are more accessible for Canadian students, as university and college tuition isn’t as astronomical as countries like the United States or the U.K. Also, our low population density and the presence of ample universities and colleges ready to accept tuition money creates an atmosphere where a larger percentage of our population gets a post-secondary education. This has led to our degrees losing their worth — even minimum-paying jobs require a post-secondary education. An exchange student commented on UBC Confessions Facebook page:

«As an exchange student at Sauder, there’s something I don’t understand. I come from a country where we have around 30-35 hours of classes a week, with essays to write and presentations to make as often as here, and where the grading system is way more harsh. However, I see more students getting overwhelmed by the amount of work here at UBC in one semester than in my three years at my home university. This semester honestly felt like holidays to me while I passed all my classes with better grades than what I’m used to.»

Canada’s high proportion of post-secondary degree holders doesn’t tell the entire story or indicate the health of our education system.

Quick integration of migrant children

I see that most of the time the children of new migrants are a couple of years ahead in math and science courses compared to their Canadian schoolmates. And often they come from countries where education is highly respected and valued. They have already achieved a level of mastery in learning and study skills that allows them to adapt to their new environment quickly. This is not a true indicator of the health of our education system, either.

We have a lot of work to do to stop the decline in our education.

Low performance variation in ‘advantaged’ and ‘disadvantaged’ children

It’s important to look closer into who is in the «disadvantaged» group to get a full picture of the situation. A large group that is «disadvantaged» in Canada is the children of first-generation immigrant parents who are highly educated and highly skilled, but because their training and education was from another country they struggle to find relevant work in Canada. Although their socio-economics may be low, these families place a high priority on their children’s education, giving our PISA results a false boost in equity. Canadian education equity needs a lot of work, as many of our students from a poor background or students with learning disabilities struggle and don’t receive the support they need.

Our students have a lot of potential. They want to learn. They want to create high quality work. Are our schools and universities willing to raise the bar on Canadian education and give our teachers the training and the support they need?

As much as it feels good for policy makers to have their egos stroked and be proud for their work being viewed as having some «superpower» status, we have a lot of work to do to stop the decline in our education. As long as we refuse to recognize the symptoms of our failing system and accept there is a problem, our situation will not get any better.

Fuente: http://www.huffingtonpost.ca/mehrnaz-bassiri/canada-has-homework-if-it-wants-to-be-an-education-superpower_a_23062342/

Users Today : 33

Users Today : 33 Total Users : 35416135

Total Users : 35416135 Views Today : 36

Views Today : 36 Total views : 3349428

Total views : 3349428