América del Norte/Estados Unidos/19 de Agosto de 2016/Autor: Durba Ghosh/Fuente: San Francisco Chronicle

RESUMEN: Cuando se reanuden las clases, los estudiantes de los Estados Unidos van a recibir los libros de texto de estudios sociales que se han debatido, reescritos y actualizados con los nuevos conocimientos. En California, los debates sobre lo que debe incluirse y cómo debe ser presentado ha sido objeto de un intenso debate en los últimos 20 años, y más reciente acaba de resolverse. ¿Cuáles son realmente estos debates, y por qué escribir la historia es tan importante? La primavera pasada, los padres y los estudiantes de la India, con el apoyo de las bases Uberoi e hindúes americanos revisaron los libros de texto de estudios sociales de secundaria. Ellos abogaron por el uso de «India» sobre «el sur de Asia» para referirse a los territorios del subcontinente indio, con el argumento de que el sur de Asia no reflejaba su identidad como indios. Asia del Sur incluye a las naciones de la India, Afganistán, Pakistán, Bangladesh, Nepal, Sri Lanka y las Maldivas. Además, el grupo instó a que los libros de texto borran toda mención de castas en la India, representan el Islam y el sijismo como ajeno al sur de Asia, y muestran que el tratamiento de las mujeres ha sido históricamente una alta prioridad para las personas que viven en el subcontinente indio. Quienes se oponen a los cambios incluyen una amplia coalición de académicos, padres, maestros y miembros de otras diásporas del sur de Asia (Sri Lanka, Afganistán, Nepal, Dalit). Ellos argumentaron que los hechos acerca de la casta y la situación de la India como una sociedad secular que había sido receptivo a la aparición del budismo, el sijismo y el Islam debe recibir prioridad históricamente establecida.Después de varias audiencias públicas y reuniones, la Comisión de Calidad de Instrucción de California acordó mantener todas las referencias a la naturaleza jerárquica del sistema de castas, pero accedió a cambiar el sur de Asia hasta la India, salvo en unos pocos lugares.Estos debates sobre qué términos a utilizar en un libro de historia puede parecer poco importante. Sin embargo, se obtienen de las preguntas que son fundamentales en cualquier democracia, preguntas acerca de la participación ciudadana y cómo las minorías deben ser tratadas por las comunidades mayoritarias. Por un lado, activistas ciudadanos que tienen un interés en el proceso cívico que lleva a los libros de texto que se adoptan en un programa de estudios es el tipo de activismo cívico positivo que las democracias liberales deben apoyar; por el contrario, estas formas de activismo pueden introducir al pensamiento mayoritario en la educación, empujando a los estudiantes a excluir a las minorías y a los que son diferentes.

As schools reopen, students across the United States will be receiving social studies textbooks that have been debated, rewritten and updated with new knowledge and research. In California, debates over what should be included and how it should be presented has been the subject of fierce debate over the past 20 years, with the most recent just resolved.

What are these debates really about, and why is writing history so important?

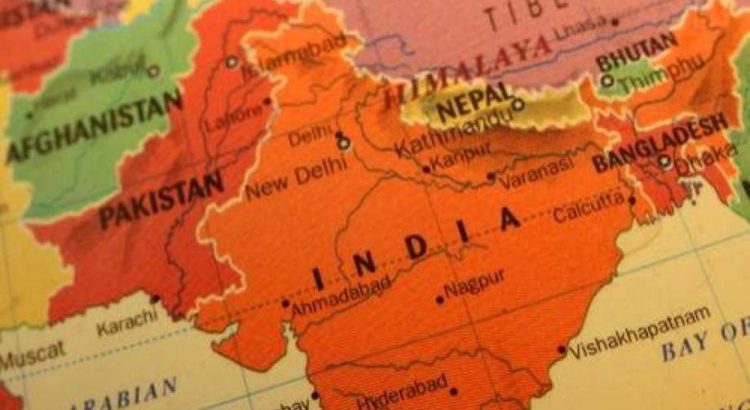

This past spring, Indian parents and students, supported by the Uberoi and Hindu American foundations, mobilized over middle-school social studies textbooks. They advocated for the use of “India” over “South Asia” to denote the territories of the Indian subcontinent, arguing that South Asia did not reflect their identities as Indians. South Asia includes the nations of India, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, Sri Lanka and the Maldives.

In addition, the group urged that textbooks erase all mention of caste in India, represent Islam and Sikhism as alien to South Asia, and show that the treatment of women was historically a high priority for those living on the Indian subcontinent. Many of those proposing changes argued from a position of injury and suggested that they were harmed or were at risk for being bullied because of Americans misunderstanding Hindu cultures.

Notably, the historical perspective that the Hindu American and Uberoi foundations supported led to a particular kind of history for India (not South Asia) that came at the expense of diversity.

Opponents to the changes included a broad-based coalition of scholars, parents, teachers and members of South Asia’s other diasporas (Sri Lankan, Afghan, Nepali, Dalit). They argued that historically established facts about caste and India’s status as a secular society that had been receptive to the emergence of Buddhism, Sikhism and Islam should receive priority.

After several public hearings and meetings, the California Instructional Quality Commission agreed to keep all references to the hierarchical nature of the caste system, but agreed to change South Asia to India in all but a few places.

These debates about what terms to use in a history textbook may seem unimportant. But they draw from questions that are central to any democracy, questions about civic participation and how minorities should be treated by majority communities. On the one hand, citizen activists taking an interest in the civic process that leads to textbooks being adopted in a school curriculum is the kind of positive civic activism that liberal democracies should support; on the other hand, these forms of activism can introduce majoritarian thinking into education, prodding students to exclude minorities and those who are different.

Common to these debates in India and the United States is a tension between majorities and minorities and the question of how to create a culture of diversity and inclusion when one group challenges another over what counts as historical knowledge about “their” communities.

If we can agree that social studies is intended to inform civic education, with the hope that young students will be engaged and involved citizens in the future, we should teach children a history that is complex and sensitive to what is positive about a given society or culture, as well as what is problematic (such as a caste system in which some members of communities were seen to be inauspicious or polluted).

In California, a process of public debate was intended to be inclusive and sensitive to a broadly conceived public, but it pitted several minority groups against one another. In the compromise forged by the commission, the textbooks ended up excluding any mention of “South Asians,” thus further marginalizing populations whose existence has been relegated to a time and space outside history. They should be working toward the goal of inclusion.

Schoolchildren should receive the kind of education that clarifies that the United States of America was built on a diversity that honors the unique histories of all minority groups.

Fuente: http://www.sfchronicle.com/opinion/openforum/article/A-textbook-debate-over-minorities-and-civic-9171711.php

Users Today : 21

Users Today : 21 Total Users : 35460404

Total Users : 35460404 Views Today : 41

Views Today : 41 Total views : 3419204

Total views : 3419204